We are publishing a six-part series looking back at Chapel Hill in 1968, and the lengthy and contentious battle to build duplexes and small apartments next to a church, and between a neighborhood of single-family homes and a shopping center.

Part 1: In-Chu Co and Missing Middle Housing: Chapel Hill’s Missing Middle Housing Battle in 1968

Part 2: In-Chu-Co: The protests start in 1968

Part 3: A push to build In-Cho-Co in Chapel Hill: ‘Is all of this Town’s vaunted liberalism phony?’

Part 4: Chapel Hill, 1968: The Death of Elliott Woods?

Where we left off: With the election of Howard Lee and two political allies, the Chapel Hill Town Council finally voted to approve the rezoning necessary to build Elliott Woods.

Part 6: For more than a year, the Inter-Church Council had patiently waited for the stars to align so they could start building Elliott Woods. Now with permission secured, they began the process of securing funding. A few months after the property was rezoned, In-Chu-Co submitted an application to the Federal Housing Authority to finance the planned 79 units, 39 of which would be at Elliott Woods and 40 of which would be on property donated by Daniel Okun, an environmental engineer and UNC professor who was active in many liberal causes. Okun’s property was located on the other side of town, between the Westwood neighborhood and Highway 54, and had been quietly rezoned for apartments the previous February.

In late December 1969, the FHA rejected In-Chu-Co’s application, finding fault with the land costs of both five-acre sites. They also noted that the Okun property was difficult to build on, and too far from shopping centers.

Adelaide Walters, who chaired the In-Chu-Co’s housing committee, said the rejection was the “last in a long series of disappointments,” but that they were prepared to continue seeking federal funding for the projects, telling the Chapel Hill News, “You learn to just take them as they come in this sort of thing. It’s gotten to the point where I’m really not too upset about it. We’re just going to keep trying.”

Five months later, in May 1970, the FHA changed its mind, calling the project “feasible,” provided In-Chu-Co could handle the high costs of land acquisition and construction. In January 1971, the Chapel Hill Town Council heard proposals to build both projects. They easily approved the plans for Elliott Woods, which didn’t appear to draw very much opposition from neighbors. However, they deferred voting on the other project due to an error in the advertisement for the March 1969 rezoning, which listed Okun’s property as being south of Highway 54 rather than north.

Once again, In-Chu-Co had to face neighbors opposed to building affordable housing nearby, citing predictable complaints about property values, mostly from residents of Westwood, an established neighborhood that was up the hill from the planned development site. A supporter of the project, Dr. Dorothea Leighton, who founded the Society for Medical Anthropology, wrote the Chapel Hill News to note how easy it would have been to join her neighbors in opposition:

The next month, the town Planning Board voted for In-Chu-Co’s project on Highway 54. Dueling petitions from Westwood residents, 26 in favor of the project and 141 opposed, were submitted to the Planning Board, with residents rehearsing familiar arguments over the need for housing (from those in favor), and the desire to protect property values and open space (from those opposed). Mason Thomas, president of the Inter-Church Council, noted that he found it difficult to speak in favor of something that some of his fellow church members opposed:

I find it tough to oppose my friends, but I care about these middle-income people who

need housing. Those opposing this project are reacting more with their emotions than

with their heads.

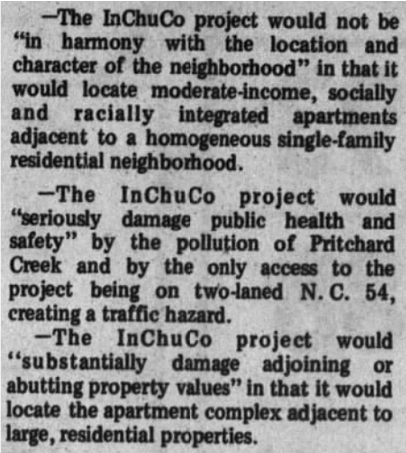

The project was approved, with conditions, including that the apartments only be accessible via Highway 54, thus cutting the project off from Westwood, one of the more expensive neighborhoods in town. Nevertheless, a group of Westwood residents, most of whom owned property immediately adjacent to Okun’s, sued the town, seeking to overturn the town council’s decision, on the grounds that special use permits were themselves violations of the “principles of zoning,” and that one of the council members who voted for the project should have recused himself due to the fact that he volunteered for the Inter-Church Council. In March, the Chapel Hill Board of Aldermen, as the town council was then known, was served a writ from the Orange Superior Court, claiming that the council had “overstepped its bounds in granting a special use permit to the Inter-Church Council” and must appear in court that June. Represented by John Manning, a Chapel Hill attorney, four Westwood property owners – Clyde C. Carter, Arthur Fink, Robert C. Harriss, and F.E. Strowd – were named in the suit, which claimed that the Inter-Church Council project would “seriously and permanently damage” their property values. More specifically:

In June, Superior Court Judge Thomas Cooper ruled in favor of the Town of Chapel Hill. Manning immediately entered an intent to appeal the decision, further delaying In-Chu-Co’s plans from moving forward. Almost a year later, in April 1972, the North Carolina Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s decision, but Manning filed another appeal, this time to the North Carolina Supreme Court. While Manning expected quick action, it took another two months for the State Supreme Court to decide to uphold the actions of the lower courts, closing out the possibility that the project would be stopped.

With council actions and legal actions out of the way by the summer of 1972, In-Chu-Co could finally go forward with its plans to build housing. In November, the Federal Housing Authority agreed to a larger mortgage, allowing construction to commence in January 1973, almost five years after In-Chu-Co first proposed building less than 100 homes for low and moderate-income families.

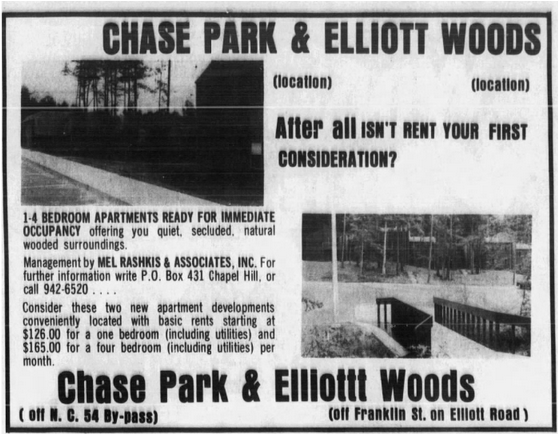

Construction took place over 1973, with both Elliott Woods and Chase Park, the name given to the apartments that were built on the Okun property, opening applications by June 1974. Advertisements for the two projects started running in late August, citing the “quiet, secluded, natural wooded surroundings.” Many of the first residents likely had no idea that this project took years of effort to bring to fruition.

In December of 1974, the Chapel Hill News ran an article celebrating the new apartments, noting that they included “people from a wide range of income levels, different professions, diverse cultural backgrounds, and various age groups.” Residents in the two complexes include a diversity of professions, including “dentists, policemen, retired elderly … graduate students, Ph.D. candidates and hospital employees.” Apartments ranged in size from one to four bedrooms and the article pointed out that the “apartments shelter white and black families as well as those of other nationalities,” thus achieving the Inter-Church Council Housing Corporation’s goals.

In the early 1980s, the Inter-Church Council changed its name to the Inter-Faith Council, which over time became known by its acronym IFC. A 1991 article in the Chapel Hill Herald noted that Elliott Woods and Chase Park were one of the few federally financed housing projects from the 1970s that had not experienced bankruptcy or turned into a market-rate complex.

Fifty years later, Elliott Woods and Chase Park are still standing, rare examples of successful privately run low- and moderate-income apartment buildings. The IFC continues its work addressing the causes and effects of poverty in our region, and provides shelter for unhoused people.

Learning from In-Chu-Co

In many ways, In-Chu-Co’s struggle to build affordable housing represents the best and worst of Chapel Hill. Adelaide Walters and other liberals who led In-Chu-Co through this process were dogged in their pursuit of what seemed at first to be a highly feasible, almost easy, project.

The generosity of local landowners, financial donations from faith communities, and individuals who donated their time and political acumen to work with federal funders allowed Chapel Hill to do something that would have been difficult for many other communities to accomplish.

In the early 1970s, In-Chu-Co built permanently affordable housing that also accomplished many other social goals, including racial and class integration, housing for senior citizens and people with disabilities, and infill housing close to jobs, shops, schools, and services.

At the same time, the project was delayed for almost five years due to the actions of other Chapel Hill residents. First, neighbors living adjacent to the Elliott Woods site protested, forcing the council to get a super-majority support to approve the project (this requirement was overturned in North Carolina in 2015), which meant that liberals needed to win an election just to build a few dozen apartments.

And, then, even after Howard Lee’s election as mayor proved that there was durable political support for affordable housing, a handful of Westwood neighbors sued the town, delaying the project another two years.

Just imagine if Chapel Hill had responded with the enthusiasm the In-Chu-Co backers expected when they first proposed building affordable housing in our community. Instead of having just Elliott Woods and Chase Park to show for their efforts, we might have another four or eight just like it, providing hundreds of permanently affordable housing in our community.

Even so, because of the persistent efforts of a few people, and the many more who have helped sustain the In-Chu-Co vision, there are eighty apartments in Chapel Hill that meet the needs of low- and moderate-income community members.

Every year, at almost every council meeting, there are votes in which council members have to decide where and whether to build housing in our community. In-Chu-Co was just one of those decisions, but it tells us so much about whether our community truly values the things it claims to believe in.