We are publishing a six-part series looking back at Chapel Hill in 1968, and the lengthy and contentious battle to build duplexes and small apartments next to a church, and between a neighborhood of single-family homes and a shopping center.

Part 1: In-Chu Co and Missing Middle Housing: Chapel Hill’s Missing Middle Housing Battle in 1968

Part 2: In-Chu-Co: The protests start in 1968

Part 3: A push to build In-Cho-Co in Chapel Hill: ‘Is all of this Town’s vaunted liberalism phony?’

Part 4: Chapel Hill, 1968: The Death of Elliott Woods?

Where we left off: After a fierce, months-long debate about building affordable housing adjacent to the large single-family homes in the Coker Hills and Lake Forest neighborhoods, the town council declines to support the Inter-Church Council’s proposal to build the Elliott Woods project.

It took an election.

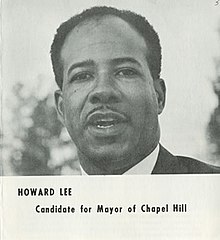

In May 1969, Howard Lee, Chapel Hill’s first, and, as of 2023, the only Black mayor, won what in retrospect was one of the most consequential elections in the history of Chapel Hill. If you’ve ever stepped on a bus in Chapel Hill or Carrboro, you have Howard Lee to thank.

A few months earlier, in January, James Shumaker, editor of the Chapel Hill News, wrote a column in which he called Lee’s entrance into the mayor’s race “bizarre,” in part because Lee seemed to be doing so much preparation for a run to become Chapel Hill’s mayor. The current mayor, Sandy McClamroch, who established WCHL in 1953 and was first elected in 1961, seemed unlikely to seek reelection, but the tradition in Chapel Hill had been for mayors to effectively appoint their successor, usually someone who was already on council. Lee, 34, had never held elected office before.

Before formally announcing his run for office, Lee focused on establishing a platform that would prevent, as Shumaker noted, “his liberal base [from] being split or confused by a radical ticket.” Lee’s platform included establishing a minimum wage law, “municipal responsibility for rents and prices,” and “dispersal of low-cost housing, preferably individual units rather than apartment projects, throughout the community.”

Shumaker’s column drew a host of critics, most of whom founded fault in Shumaker’s dismissal of Lee’s ambitions and the mention that Lee met with the “convicted draft dodger” and leftist activist George Vlasits at the Church of the Reconciliation, the same church that had donated its land for the Inter-Church Council’s proposed Elliott Woods project.

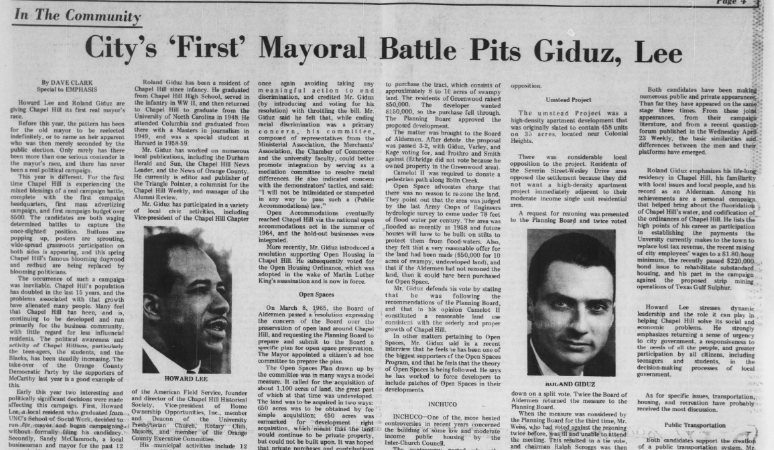

In March, council member Roland Giduz, who voted against the Elliott Woods affordable housing project in October, entered the mayor’s race, citing his experience in elected office. Giduz resigned his position as Alderman, which he had held since 1957.

The fact that town voters were making a choice at all was significant. As the Daily Tar Heel noted in late April, the Lee-Giduz contest marked the first “real campaign battle” in recent memory, with both Lee and Giduz investing in campaign advertising and grassroots organizing. While Giduz ran on a more moderate platform, calling for expanded benefits for municipal employees and a municipal recreation program, and cited past accomplishments on council, Lee called for a range of ambitious policies, including starting a public transportation system, a comprehensive planning strategy, and a more active role for the mayor.

While public transportation was the number one issue in the campaign, the second most important issue was InChuCo’s plan to build affordable housing adjacent to the Lake Forest and Coker Hill neighborhoods. As the Chapel Hill News noted just over a week before the May election, one of Lee’s first public statements was a defense of the project, while Giduz voted against it.

During the campaign Giduz claimed that he almost always voted to uphold the recommendations of the Planning Board, but the Daily Tar Heel noted in late April that he voted against the Board’s recommendations at least nine times. (According to the paper, Giduz also said that he was against the project because “the area was becoming less and less an apartment type area.”)

While Giduz refused to opine on whether he would support Elliott Woods or not, Howard Lee expressed his full support of In-Chu-Co’s project.

Election Day was May 6.

Elections and Consequences

Lee won with 54 percent of the vote, attracting 2,566 votes to Giduz’s 2,116 votes. With the reelection of two allies, Joe Nassif and Mary Prothro, Lee had a majority on the town council. Two council members allied with Giduz, Ross Scroggs, formerly chair of the Planning Board, and George Coxhead, also won seats, but two other incumbents, who were not up for reelection, gave Lee a 4-2 majority on the council.

In his victory speech, Lee, the first Black person in almost a century to win a mayoral contest in North Carolina, noted that there was a “new day dawning” in Chapel Hill. Soon after his election, he told the Chapel Hill News that he was a “patient, aggressive man,” neither militant nor passive, eager to work within the system to enact change. He took office the following week.

On June 3, less than a month after Lee was elected, the Planning Board reviewed the InChuCo project once more. The Planning Board voted to approve a broader plan for rezoning the area, including Elliott Woods. The Interchurch Council also put forward its own rezoning request, which would only apply to their site, which gave the council options for approving the rezoning.

Unfortunately, this was not enough. Because local property owners protested the rezoning, the council needed to pass it with 3-4ths support, which meant just two of the six council members could prevent it from going forward. (The Mayor only voted in the case of a tie). Scroggs and Coxhead voted against the rezoning. Despite Lee’s victory in May, by July it seemed that InChuCo’s plans were no closer to being realized than they were the previous October.

However, this time, council member David Ethridge, one of Lee’s staunchest allies, resolved to keep the issue alive. As the Chapel Hill News noted in early July 1969, under council rules, rezonings can “legally be brought up for the Board’s consideration at every regular and special meeting, until it is defeated by an absolute majority.” Ethridge resolved to keep In-Chu-Co on every meeting’s agenda for the next year until it was approved.

He didn’t have to wait long. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong stepped foot on the moon, completing the goal of the Apollo missions, which had launched its first crewed flight less than a year earlier. Eight days later, the Council finally approved the rezoning request from Inter-Church Council, which the council had been considering for almost twice as long.

Council member Scroggs switched his vote, claiming that his earlier no vote was due to a misunderstanding, giving the project the necessary five votes to pass. While no one protested the rezoning, perhaps because the matter was settled, the Chapel Hill News reported that “additional skirmishes over the proposal are expected when the Interchurch Council applies for the necessary special use permit.”

That August, the Inter-Church Council noted that there were 31 families, with a total of 137 children, who were living in houses that had been condemned. Families lived in houses without running water and slept on pallets. Others had an outhouse, but no longer used it because it had been taken over by snakes. Rats and roaches overran other homes, but families had nowhere to go. There was a housing emergency in Chapel Hill and it was getting worse every year. But the town council wasn’t acting fast enough to address it.