We are publishing a six-part series looking back at Chapel Hill in 1968, and the lengthy and contentious battle to build duplexes and small apartments next to a church, and between a neighborhood of single-family homes and a shopping center.

Part 1: In-Chu Co and Missing Middle Housing: Chapel Hill’s Missing Middle Housing Battle in 1968

Part 2: In-Chu-Co: The protests start in 1968

Part 3: A push to build In-Cho-Co in Chapel Hill: ‘Is all of this Town’s vaunted liberalism phony?’

Part 4: Chapel Hill, 1968: The Death of Elliott Woods?

Where we left off: In Part One, The Inter-Church Council has secured strong public support for its plan to build 39 homes on Elliot Road on land owned by the Church of the Reconciliation. The editor of the Chapel Hill Weekly warns that nearby neighbors will not be happy about the proposal.

Part Two: The day before the town council was set to vote on its plan to build 39 apartments for moderate-income people in Chapel Hill, the members of Inter-Church Council, which headline writers charmingly called “In-Chu-Co,” had to be optimistic.

Fifteen congregations had promised a total of $13,700—almost $120,000 in today’s dollars—to help the project meet its initial financing requirements of raising $25,000 from local sources. The overall project was to cost $1.25 million, with the federal government providing a 100 percent loan to pay for construction. An article that ran the day before the hearing reminded readers that the project came together after a 1967 study by the ICC found that almost 1,000 families in town “occupied substandard housing” and many others “had to commute to work daily from neighboring towns.”

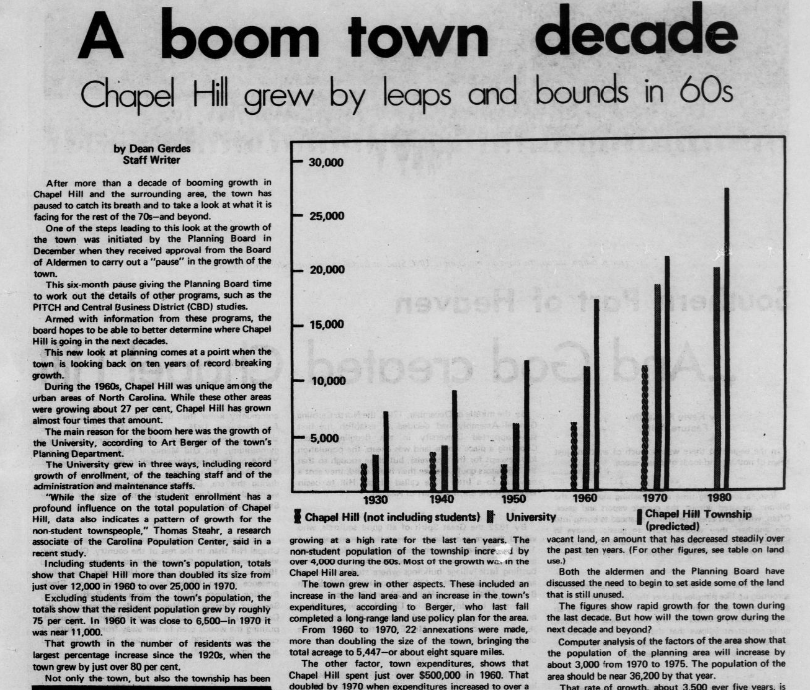

On the front page, the Chapel Hill News noted that delegates from Coker Hills and Lake Forest were “expected to protest” the ICC’s request, but the zoning discussion was one of many controversial items on the agenda. Even more than now, all the council seemed to do was to hear development requests in fast-growing Chapel Hill, which doubled in population between 1960 and 1970. In many respects, it seemed to be just another town council meeting.

The protesters arrive

Only military metaphors seemed to suffice. When the Chapel Hill News published its account of the Monday night meeting two days later, the headline read “Housing Project Draws Heavy Fire.” The opening paragraphs are worth reprinting in full:

![Before a jam-packed crowd of more than 300, supporters and opponents of a proposed five-acre low-rent housing development near the Coker Hills and Lake Forest sections of Town debated for nearly two hours Monday night.

The debate came on a request by the Inter-Church Council to rezone a tract of land on the north side of Elliott Road between Franklin Street and Old Oxford Road for a unified housing developmnet [sic] of 39 units.

The Aldermen, at what turned out to be one of the longest and largest hearings on record, referred the rezoning and special use request to the Planning Board for a recommendation.]](https://triangleblogblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Screenshot-2023-03-06-at-20-28-24-In-Chu-Co-Missing-Middle-Housing.png)

The town meeting minutes did not list the size of the crowd, but did make note of the number of people who petitioned against rezoning the site (200), how many people spoke about the project (13 in favor, 5 against) and what time the meeting ended (11:05 pm). The newspaper gave more details about the neighbors’ complaints about the project, including its potential to bring about a “decrease in property values, increased traffic congestion and a change in the character of the neighborhood.” The unidentified writer of the story wryly noted in the next paragraph: “Adjacent residents in the Lake Forest and Coker Hills neighborhoods average about one acre per lot.”

Several nearby property owners hired their own legal representation, Robert Midgette, who was active in civic affairs and represented developers and neighbors alike in local cases. Midgette claimed that in 1963 the town had rejected a previous effort to change the zoning on the piece of property, and suggested that “apartment construction in a single-family residential area was the main concern of his clients—not the racial or social overtones inherent in low-rent developments.”

Countering Midgette’s claims, F. Stuart Chapin, who represented the ICC, noted that the town should factor the housing shortage into its consideration, and that the project’s use of multi-story buildings would preserve “wooded open space.” Left unmentioned was Chapin’s day job, as a professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UNC, which made him unusually qualified to speak on questions related to planning. A pastor and local resident also spoke emphatically on behalf of the project, arguing directly against the “neighborhood character” concerns.

![[“I believe the the appearance of a neighborhood belongs to houses, but that character belongs to people. The character of the neighborhood might be improved by this project.]](https://triangleblogblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Screenshot-2023-03-06-at-20-30-55-In-Chu-Co-Missing-Middle-Housing.png)

Another resident complained that his son was “culturally deprived” due to the lack of diversity in the neighborhood. A resident who lived a half-mile away said apartments shouldn’t be in a residential area. A local developer, Peg Owens, asked for her remaining land in Lake Forest to be rezoned to eight units an acre to make up for the decline in nearby property values that she anticipated. The Chapel Hill Board of Realtors weighed in with strong opposition to the plan.

The Council decided not to vote that evening, sending the matter back to the Planning Board for more study. On the opinion page the editor wondered whether the town’s many private swimming clubs would rescind their whites-only admission policies.