Chapel Hill’s proposal to allow property owners to build more types of housing on their own properties is going before the Town Council on Wednesday January 25 for a public hearing, and it’s sure to draw a large crowd of public commenters. There will be a lot of people there speaking in favor of the policy, which will allow people to build duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes, as well as cottage home developments, on their own land. (Don’t worry, if you own a single-family house, no one is going to make you build a duplex).

As we’ve said before, ever since way back in September 2022, and again in October, and several times this month, we are thrilled that Council is following the lead of Durham, Raleigh, and towns throughout the nation by updating its zoning code to encourage the production of more housing. We think this proposal is a great and necessary first step in reversing decades of restrictive housing policy in Chapel Hill.

But, as is typical where these types of changes as is proposed, we expect lots of current homeowners will turn out to oppose the proposals. (And, if they’re anything like the typical Chapel Hill/Carrboro public speaker, they’ll be older, whiter, and wealthier than the average citizen.)

While no one has reached out to us with copies of their comments, we are certain that the following themes will be common. Here’s some of what we have seen in the emails that have been sent to Town Council so far (a group that, once again, is older, wealthier, and whiter than the average Chapel Hill resident):

This proposal will hurt our property values

This breed of commenter complains that the added noise and activity from this more dense housing will push down their property values. It echoes the infamous line from the Supreme Court case Village of Euclid v. Amber Realty which ruled that zoning was constitutional: “the apartment house is a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district.” Here are two examples:

“It is my understanding that many Council members support this elimination of R-1 zoning – perhaps especially those whose own lives and property values would not be affected by such a decision, such as those members who live in condominiums or neighborhoods with covenants that would prevent multiple dwellings from being built on a lot. It’s easy to support something and try to frame it as a public good when your own residence and property value would not be affected.”

“[T]his would also plunge our and the town’s affected areas property values and likely make other local areas more attractive for homeowners. I don’t think we want Chapel Hill to look like downtown Durham.”

One flaw with this argument is that there’s no evidence whatsoever that this would happen.

This proposal will increase property values

Some email comments are sure that the housing choices proposal will cause property values to skyrocket, forcing out lower-income residents and people living on fixed incomes.

“The proposal to upzone neighborhoods throughout Chapel Hill for greater residential density will likely increase the appraised value, and thus the tax liability, of the upzoned parcels. What steps does the Town plan to take to protect existing homeowners from being displaced by the tax increases related to the zoning change? It would be tragic indeed if a legislative action undertaken to make housing more affordable ended up making existing housing less affordable and displacing the town’s least affluent homeowners.“

This at least is a rational argument. But once again there’s a lack of strong evidence that this would be the case, and some evidence to the contrary. Some have pointed to a study of targeted rezonings in Chicago which found increases in property values and little new construction, but the study’s author, Durham native Yonah Freemark, has specifically said that’s a misreading of the study.

This proposal will cause tear-downs of existing homes

Some are concerned that historic and smaller homes in their neighborhood will be torn down and replaced:

“However, I can assure you, if low density zoning (such as R-1/R-2) is eliminated, any remaining small homes and cottages in my area and all around the campus will be targets for teardown, to be replaced by large and expensive homes or townhomes, forever altering the character of what remains of “old Chapel Hill.”

A big flaw of this argument is that today, someone could tear down a small home and cottage in town and replace it with a large or expensive single-family home. There are several examples of this all around town. And the plan includes some policies to address this issue, such as by not changing any of the setback or floor-area or height requirements, requiring the same minimum lot size, and including design and stormwater requirements for triplexes and fourplexes.

This is probably a good point to bring up the ridiculous brouhaha over the $2 million townhouses in Raleigh. Taking advantage of Raleigh’s recent changes to allow more types of housing in more parts of the city, a developer is planning to tear down a 100-year-old mansion and build 17 townhomes which will sell for around $2 million each. The claim, of course, is that $2 million townhomes are not affordable. Obviously. But let’s look at the context:

- These townhomes are being built in a tony part of town, the exclusive Hayes Barton neighborhood. In December 2022, the median sales of a home was $1.7 million.

- The home was on a 2.5-acre lot, where 17 families will get to live. Sure, they’ll be wealthy families. Sure, they won’t be affordable to school teachers. But is it worse having 17 $2 million homes instead of one $5 million home?

- Speaking of $5 million, that’s the Zillow estimated price of a home three doors down from this site. Other homes in the area have an estimated price of $2-4 million. There is no conceivable scenario in which “affordable” housing would be built in this neighborhood.

What we have here is a wealthy neighborhood where instead of just absurdly expensive single-family homes, there will also be merely very expensive townhomes available for purchase. The people who are able to purchase those 17 townhomes will no longer be competing for other homes in Raleigh. We don’t see the issue.

Questions, questions, questions

We have no doubt that speakers at Wednesday’s meeting will point out lots of unanswered questions that that town staff simply must answer before council can vote on this plan — so many questions, in fact, that we should wait to hold a vote until next year, well after the November elections for the mayor and four council members have been held.

But, let’s be clear. There is no constellation of answers that will satisfy the bulk of people loudly expressing their opposition to this policy. No study is going to provide the conclusions they will accept. If a study says the change will help property values, then the proposal will be blasted as pushing lower-income people out of their homes. If the study says the change will lower property values and the cost of housing, it will be criticized as hurting residents’ primary asset for retirement. If a study says there will be no appreciable impact on traffic, on safety, on the sewer system or on electricity, the assumptions will be challenged and the conclusions rejected. The consultants got it wrong, they’ll say, and we need a citizen committee to redo the work. It’s a no win scenario.

The goal is to delay delay delay until our elected officials lose their nerve, or a small slice of the electorate can be persuaded to go to the polls and vote out the supporters of the plan in the fall.

Neighborhood Character

One phrase that will repeated ad nauseam on Wednesday is “neighborhood character.” Speakers will claim that allowing duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes in neighborhoods that have only ever allowed detached single-family homes will ruin the family-oriented character of their neighborhoods.

It’s worth thinking where this concept of “neighborhood character” originated. We like to think that zoning ordinances were a noble effort to protect people from living close to dangerous conditions, like factories. They did do that, but they also were designed to reinforce America’s historic system of segregation. The neighborhood character is the result of real estate covenants and zoning regulations that were designed to exclude. The people who were blocked from these housing developments included those are poor — the “parasites” that the Supreme Court identified — and, particularly in the south, those who were not white. (Remember, zoning ordinances did not protect our African-American neighbors from living next to a landfill for decades.)

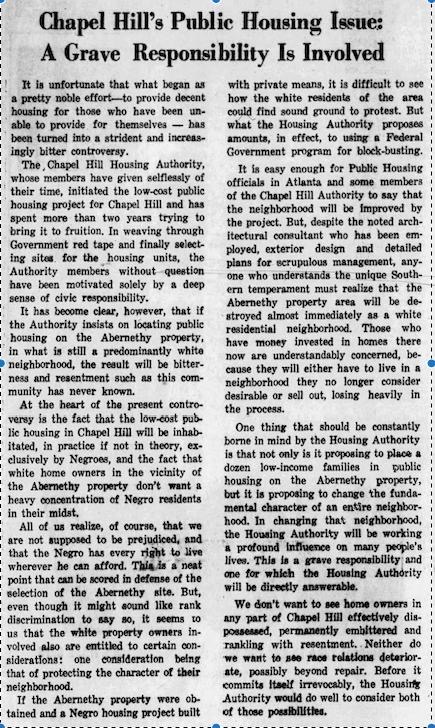

In 1964, the Chapel Hill Weekly wrote how a proposed public housing project would impact neighborhood character. The entire editorial is printed in full at the end of this post, and here is the key piece:

At the heart of the present controversy is the fact that the low-cost public housing in Chapel Hill will be inhabited, in practice if not in theory, exclusively by Negroes, and the fact that white home owners in the vicinity of the Abernethy property don’t want a heavy concentration of Negro residents in their midst.

All of us realize, of course, that we are not supposed to be prejudiced, and that the Negro has every right to live, wherever he can afford. This is a neat point that can be scored in defense of the selection of the Abernathy site. But, even though it might sound like rank discrimination to say so, it seems to us that the white property owners involved also are entitled to certain considerations: one consideration being that of protecting the character of their neighborhood.

If the Abernethy property were obtained and a Negro housing project built with private means, it is difficult to see how the white residents of the area could find solid ground to protest. But what the Housing Authority proposes amounts, in effect, to using a Federal Government program for block building.

…

One thing that should be constantly borne in mind by the Housing Authority is that not only is it proposing to place a dozen low-income families in public housing on the Abernethy property, but it is proposing to change the fundamental character of an entire neighborhood. In changing that neighborhood, the Housing Authority will be working a profound Influence on many people’s lives.

When residents claim these zoning changes will hurt “neighborhood character,” this is the history they are defending, something Howard Lee, the town’s first African American mayor, experienced in 1964, when he moved to Colony Woods (and found only one realtor who would work with him).

“For the next year, we lived under threat of death,” he said. “And our kids were threatened when they went to school.”

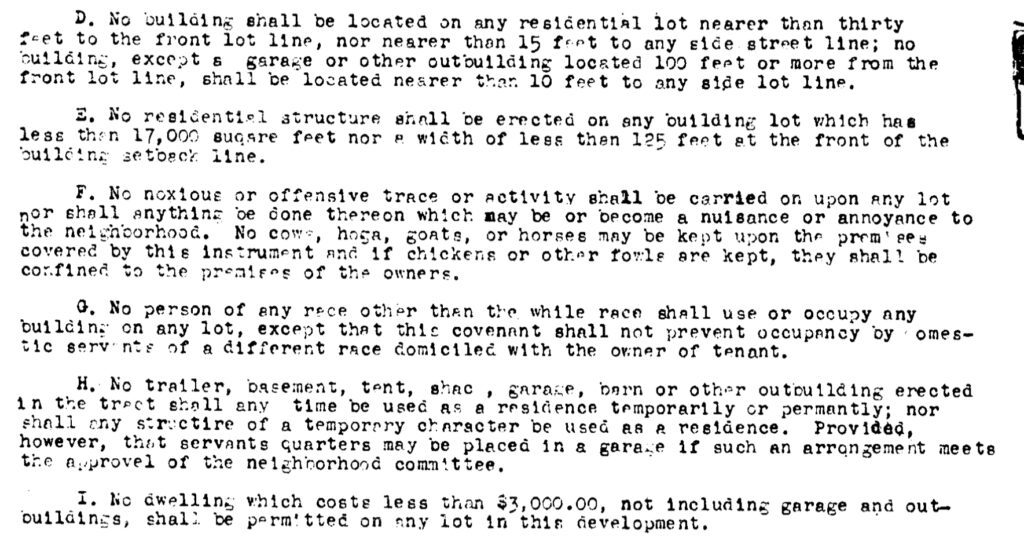

Common features of Chapel Hill real estate covenants from the 1930s through the 1960s are other exclusionary provisions that target poor and African-American families. Many covenants included explicitly racial prohibitions. Here’s one from 1941:

The above covenant from 1941 states “No person of any race other then the while race shall use or occupy any building on any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with the owner of tenant.” This provision is mixed in with other elements requiring minimum setbacks, minimum lot sizes, and restricting the number of dwellings on the site. All are integral parts of a scheme to exclude “parasites” from the neighborhood.

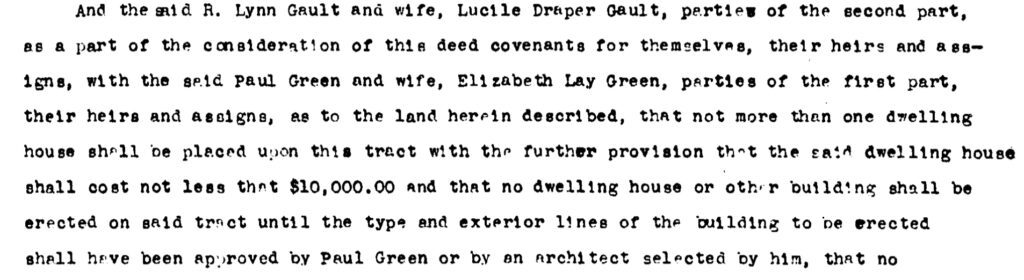

And here’s one from 1945 which blocks poor people:

We have come a long way since 1964. We look forward to the public hearing Wednesday and taking the next steps towards ending our arbitrary system of exclusionary zoning, a system that today blocks the production of needed housing and contributes to making our town unaffordable to most people.