On Tuesday night, around 8:40pm, shouts of “Shame! Shame! Shame!” broke out at the North Carolina General Assembly. The House, in a 72-48 vote, had overrode Governor Cooper’s veto. Now, a 12-week abortion ban (see below) will go into effect on July 1.

Make no mistake: people will die because of this decision.

We spoke to Dr. Rebecca Kreitzer, an associate professor of public policy and an adjunct associate professor of political science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who studies reproductive rights and inequality. She wrote this excellent piece earlier this month analyzing the new abortion bill – the most detailed and nuanced reporting we’ve seen on the topic. Her Twitter account is a must-follow on the topic.

All of the headlines we’re seeing call this a 12-week abortion ban, but when we spoke earlier, you told us not to call this a 12-week abortion ban. Why not?

This law bans abortions earlier than 12 weeks, and it puts in place a lot of obstacles before someone can get an abortion, even early on in pregnancy. It requires extensive, burdensome and medically unnecessary reporting that collectively raise serious questions about patient data privacy and security, for both patients and providers. Additional requirements place various administrative burdens on the providers, limit where certain abortions can occur, and require multiple in-person appointments – all of which raise the cost of accessing and providing abortion, thus making abortion care less available, even before 12 weeks. Let me give you a few examples (and you should know this is a very incomplete list of what this law does):

Before getting any abortion in NC, people need to complete an “informed consent” process and sign a bunch of attestations that they received certain information from the provider. They have to do this at least 72 hours before getting an abortion, not including holidays or weekends. It’s one of the longest waiting periods in the country. Right now it’s almost always done over the phone. This law would require this appointment take place in person.

It’s worth noting, research indicates providing this process over the phone is not only a convenient option for mandated pre-abortion consent visits – it’s associated with high levels of patient satisfaction and reduces the burden of travel and associated barriers, especially those that live further away from a clinic.

Medication abortion, which is the most common type of abortion in the US, would only be available up to 10 weeks. Patients would need to go to an informed consent appointment, then 72 hours later return for a second appointment, and then would be pressured into attending a third (completely medically unnecessary) in person appointment 7-14 days later.

Right now medication abortion is available in NC up to 11 weeks, which is a protocol supported by scientific research demonstrating safety and efficacy. Proponents of the law say it is good policy to require doctors to closely follow FDA guidelines, which currently authorize the current medication abortion protocol for use through 70 days (10 weeks). But clinical research suggests these guidelines may be outdated, the FDA has long over-regulated access to medication abortion because of politics, and it’s common for doctors to not follow FDA guidance precisely by prescribing “off-label” anyway.

The content conveyed in the mandatory informed consent has also increased. This information emphasizes the risks to abortion, even though abortion is 14 times safer than childbirth, and more than 95% of women do not regret their abortion immediately or 5 years later. If the fetus is seriously ill, the abortion provider must now go through details of the fetal diagnosis with the patient (even though most abortion providers are not experts in the broad array of complex fetal diagnoses, and patients scheduling an appointment at an abortion clinic because of a fetal diagnosis likely have already had serious conversations with their own provider.) They must also receive information about palliative care and neonatal care options should they decide to continue the pregnancy. They have to get another ultrasound. They must then wait another 72+ hours before they come back to get an abortion.

If a patient is raped, they also face a grueling informed consent process in which they must be told about the legal requirements of their rapist to pay child support should they continue the pregnancy, among other things. They must also discuss with the provider the circumstances surrounding their pregnancy in enough detail that the provider can report that information to the state. Then, they have to get an ultrasound, and go back to their home or hotel to wait until they can come back to receive care.

There are already many restrictions in place on where abortions can take place. As a result, most parts of North Carolina have no abortion providers. This law increases the regulations of where abortions can take place, requiring that abortions take place in hospitals after 12 weeks, even though this isn’t medically necessary. The vast majority of abortions in the US take place in outpatient clinics – in part because abortions are incredibly safe, in part because it’s more efficient for common out-patient procedures to occur in clinical settings, and in part because the politics of abortion has siloed abortion care outside of many traditional healthcare settings. Requiring abortions occur in hospitals further reduces access to abortion, especially as hospitals are not set up to provide routine abortion care. It increases the cost of abortions, as the overhead costs of care in hospitals is greater than in clinics.

In the first six months after Dobbs, abortions in NC went up 37 percent. And that was when only a few states banned abortion outright. More and more states are banning or nearly banning abortion – and many of the people from those states have sought healthcare in NC. This law makes it harder for them to get abortion, as they will now need to negotiate cross-state travel before 12 weeks in pregnancy, secure an appointment, and then stay long enough to attend all mandatory in person appointments. This makes abortion really expensive, and many abortion funds are unable to provide money for travel.

And again: as more people (from across the state and country) try to get abortions appointments squeezed in before 12 weeks, it makes it harder for everyone to secure appointment slots, even those trying to start the process before the gestational ban of 12 weeks.

What else is in the law?

This law also requires extremely invasive reporting. NC law already requires physicians to report about abortions they perform, and this data is aggregated and used for statistical purposes by the state to give a broad overview of the incidence of abortion. This new law takes reporting to a new level.

After each abortion, a report must be submitted to the state that “shall contain, at a minimum, all of the following:” 1) identity of the physician and any referring physician, 2) the location, date and type of any surgical abortion or the location, date, and the location of “where any abortion-inducing drug is administered or dispensed”, including any healthcare facility, at the pregnant person’s home, or an other location, 3) the patient’s county, state, and country of residence, age and race; 4) the patient’s fertility history, including number of live births, previous pregnancies, and number of previous abortions; 5) patient’s pre-existing medical conditions; 6) probably gestational age of the fetus as determined by both patient history and ultrasound, and the date the ultrasound was done; 7) the abortion medications used and the date they were dispensed, administered and used; 8) whether the patient returned for the state-mandated follow up appointment, the results of that appointment, and the date; 9) the reasonable efforts of the provider to encourage the patient to attend the follow-up appointment; 10) any complication; and, 11) amount of money billed to cover the treatment for complications, including the diagnosis codes reported.

While the law says that social security numbers and driver’s license numbers wouldn’t be collected – it would not be hard for the state to combine the data that will now be recorded with other data the state has about its citizens to identify individuals, and to identify the providers that provide abortion care frequently, or that refer patients for abortions. The sponsors of the bill have not explained how this data will be used, or who will control it, despite being asked about this by Democrats in floor speeches and journalists at press conferences.

When asked about why this extremely detailed data was needed by the state government, one senator said that the data collection would be used to track concerns about mifepristone being mailed to young women across the state. Obviously the data required here goes way past that.

But wait – there’s more! If the person is seeking an abortion after 12 weeks because of a medical emergency, the provider must explain the “findings and analysis” on which the doctor determined there to be an emergency. This delays care. The law specifically states that the medical emergency can not be psychological or emotional – so a person who is suicidal would not be allowed an abortion. If someone has a significant health concern that makes pregnancy dangerous – unless they are at immediate risk of dying, they would not be allowed an abortion. If continuing the pregnancy would exacerbate a dangerous pre-existing condition, unless it becomes a medical emergency, abortion would not be allowed.

If the person seeks an abortion because of a “life limiting” and “diagnosable” fetal anomaly, they must report details of the fetal diagnosis and referring physician. Abortions wouldn’t be allowed for fetuses with a diagnosis of Down Syndrome, even though that is life limiting and diagnosable. (Worth noting – the law allows for abortions for fetuses with a life limiting diagnosis, but it does not allow pregnant women that same right.) If the person seeks care because of rape, the provider must sufficiently interrogate their patient to confirm their circumstances so that this can also be reported to the state.

If a provider at an ER suspects someone is experiencing an “adverse event” from medication abortion, that must be reported to the state, including if the patient self-sourced the medication, and a bunch of private information about that individual. This reporting requirement may dissuade people from seeking care. It’s also not that useful of data – many people who go to ERs after a medication abortion do so because they are experiencing cramping bleeding, and they aren’t sure if it’s a normal amount. In most cases, the patient simply needs reassurance. It might make sense for the state to request reports of serious complications relating to abortions, but again, this goes way past that.

The law also bans advertising, having a website or otherwise providing services to help pregnant people who are a “resident of this State” obtain medication abortion pills – a potential free speech issue that also raises real questions about what enforcement could entail. It prohibits telemedicine (the mailing of medication abortion pills through the mail). It does a bunch of other stuff as well.

You’re interviewed a lot about abortion, especially in recent months. What do you wish reporters would ask you?

One of the biggest challenges for reporters covering this issue is that reporters aren’t in the habit of reporting on reproductive health. The journalists who have been writing about abortion in meaningful ways, in the most depth, and for the longest time are not at the most widely read outlets – they tend to be at more niche places, like Rewire, and substack newsletters like this one by Jessica Valenti.

So, when I talk to the more “mainstream” media, our conversations can run 5-45 minutes, and many reporters start out by asking me what they should know. I spend a lot of time explaining pretty basic things and combating rampant misinformation.

Reporters aren’t the only ones who need to learn more basic information about pregnancy and abortion – their readers and our lawmakers desperately need this information as well. So, I try to find time to explain the basics whenever necessary. Part of the reason this “starting at the basics” is so important is that, for decades, people haven’t really talked about things like pregnancy complications, pregnancy loss, infertility, and abortion openly, so there is a lot that people don’t quite understand. But that doesn’t always leave as much time to get into nuance and context.

The reality is that because many reporters are newer to covering reproductive health and rights, reporters often ask me “What else should I ask?” My honest answer is that I could talk for 6 hours if you let me. There is a lot to say.

My blog post to explain SB20 is 9 single-spaced pages and there is more I could have said. Reporters face real constraints on word counts, and their articles have to remain relatively focused. The reality is that I have a lot of really interesting conversations with reporters that don’t necessarily show up in tangible ways in the stories they write (like in direct quotes). I hope that our conversations are useful in guiding the direction of their future reporting, how they think about these issues, and how they frame/contextualize abortion in their writing.

In part because most media is not in the habit of talking about reproductive health, rights or justice, there is frankly a lot of ground to cover to make up for lost time. There are so many important stories that have gone untold, or told only to small audiences that seek out those articles. There need to be more reporters writing on these issues from a variety of angles – including local reporters. They need to get more prominent page space!

You analyzed the word count of the bill, topic by topic. What did you learn?

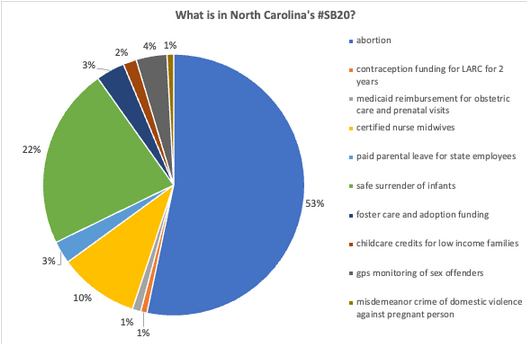

Proponents of NC’s new abortion law claim it isn’t focused on abortion because it does other important things for maternal and child health. Technically it does. But meaningfully, it does not. This figure shows the word count, topic by topic, across the bills.

There are 2 sections of the bills that are basically their own separate bill. There are 11 pages on the safe surrender of infants (which was how this abortion law started anyway), and about 5 pages on extending the scope of practice for certified nurse midwives (which another bill introduced in the the NCGA would have done without being attached to this hodgepodge bill). And then some of the topics on “maternal and child health” are mere sentences. Some things are even more limited than it seems at first glance. The funding for contraception is for 2 years. The increase of childcare reimbursement rates for low-income families is good but doesn’t do anything for the 30,000 kids on waitlists for childcare. Only 10% of children eligible for childcare benefits based on federal guidelines are currently receiving them. The creation of a paid parental leave policy is only for state employees, most of whom are not women of reproductive age. The leave is 8 weeks for birthing parents and 4 weeks for non-birthing ones, and even less for part time employees. Every one of those topics is deserving of its own attention by the NCGA.

What now? What next?

We should expect health outcomes to get worse for women, children and families – the very groups this bill claims to protect. Maternal mortality is associated with restrictive abortion laws, and evidence from other states makes clear that the new spate of post-Dobbs abortion bills result in poorer quality of care for pregnant people.

The aspects of this law ostensibly about protecting children and families are mostly symbolic, but North Carolinians should hold our legislators accountable, and push conservatives to truly fund policy that helps more families.

More restrictive abortion policy could come to NC. Conservative lawmakers and legislative staff have indicated this law and other abortion laws could change in future sessions. While the slim margin by which this bill became law (including the veto override) likely means a more restrictive abortion policy couldn’t pass in this session, abortion will be a considerable issue in the next election. Some prominent Republicans, including Lt. Governor Mark Robinson – one of the candidates who has announced they are running for Governor – have openly indicated support for complete or near complete abortion bans. One aspect of this law pertains to licensure of abortion clinics, and wouldn’t go into effect until October 1st

Abortion isn’t the only major issue that Republicans in the state are trying to change in major ways. Bills are being considered that restrict access to evidence based gender affirming healthcare (which reduced suicides among trans people), ban public performances of drag, further weaken the sex ed taught in schools, to micromanage what can be taught in our schools (through bills trying to ban content on race and gender as well as mandating specific texts college instructors should assign).

You can follow Rebecca Kreitzer on Twitter.