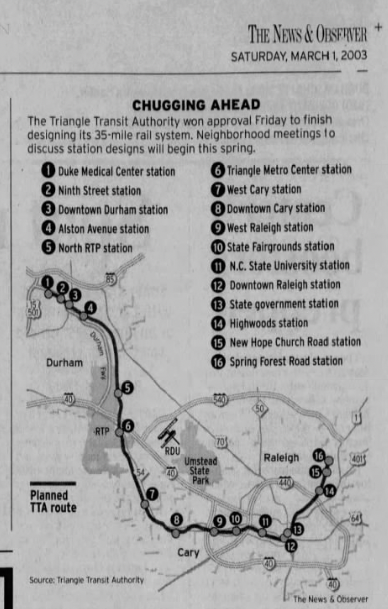

My recent piece on the proposed Commuter Rail Project received some pushback, including from TBBer Melody Kramer. Most of the criticism made two points: 1). Highway spending is just as wasteful, and we never hear criticism of highways, and 2.) If we don’t support this project now, we’ll regret it in the future.

While I’m sympathetic to both arguments, I think they’re wrong, for reasons I’ll get into below. But, first, I wanted to outline what I think advocates for public transportation, bicycling, and other non-car oriented ways of getting around should consider before endorsing a new project.

- Is it a good project?

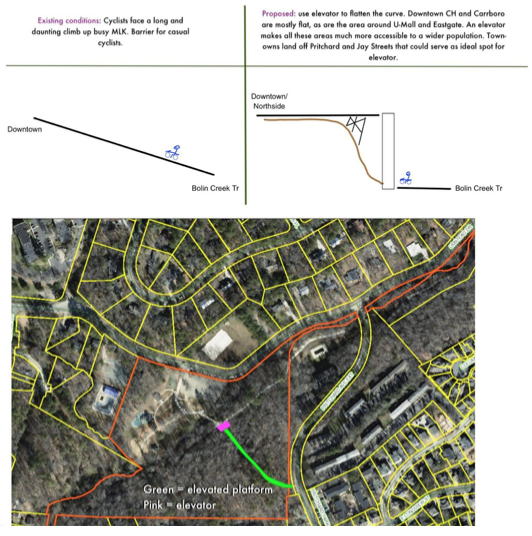

When the Town of Chapel Hill was planning a connection from Bolin Creek Trail to Northside, they had to figure out how to deal with the elevation difference. One goofy solution proposed by TBB writer Stephen Whitlow was a bike elevator:

This is an intriguing idea, but also a terrible one. (Ed note: That’s a matter of personal opinion, Martin.) Public elevators often break, and in places where there are few bathrooms, come to serve as unofficial urinals. In addition, elevators have limited capacity, and we doubt people would want to wait five minutes to get to the top of the hill.

A bike elevator would have been a bad project even if someone offered to pay for it, because it would have replaced a much better one, the Tanyard Branch Trail.

2. Will it serve enough people?

One of summer’s great pleasures is going out to Maple View Farms to get ice cream. The pastoral view from their porch provides one of the strongest defenses for the rural buffer.

But you can only get there if you have a car, or if you’re able to bike 14 miles (round trip) on the open road. Wouldn’t it be nice to take the bus?

Yes, but, because of the rural buffer, there’s nothing else out there. While there might be enough demand for an ice cream bus in the heat of the summer to make it worth running, on most days it would be empty, costing Chapel Hill Transit money that could be used to run buses where people actually live.

3. Is it worth the cost?

Downtown Chapel Hill and UNC’s main campus sit on the top of a hill, which is challenging for walkers, people in mobility scooters, and cyclists. Other places have hills, and a few have built aerial trams to transport people from the bottom of the hill to the top.

Let’s imagine that we replaced Merritt’s Grill with a gigantic parking deck topped by an aerial tramp. If we closed all the other parking decks closer to the hospital, the aerial tram from there to UNC Hospitals would likely carry enough riders, but at marginal benefit. (Not to mention the B.L.T.’s we’d lose)

An aerial tram that traverses about .62 miles was recently built in Portland, Oregon for $57 million, a third of the cost of what Chapel Hill is expected to spend on its 8.2-mile NS BRT line, which will serve a lot more people, including UNC Hospitals.

4. Is it politically feasible?

At a recent complete communities meeting, Jennifer Keesmaat suggested that Chapel Hill consider converting the railroad spur currently used by UNC’s cogeneration facility into a greenway. This is a fantastic idea, one that’s been discussed for decades.

But, it’s unlikely to happen any time soon. In 2010, Holden Thorp, then the chancellor of UNC, promised to close the facility by 2020. For reasons that are too complex (and sad) to get into here, that didn’t happen, and now it seems that UNC will operate the plant for the foreseeable future. Recently, Norfolk Southern, which operates train service on the track, repaired its railroad ties, suggesting that they don’t believe that the train is going out of service.

Of course, there are activists who are trying to get UNC to close the plant, and I support them. There’s a place for activism that is focused on long term goals. But there’s also a place for activists who want to be involved in making good projects happen in the near term.

5. Does it align with a bigger vision?

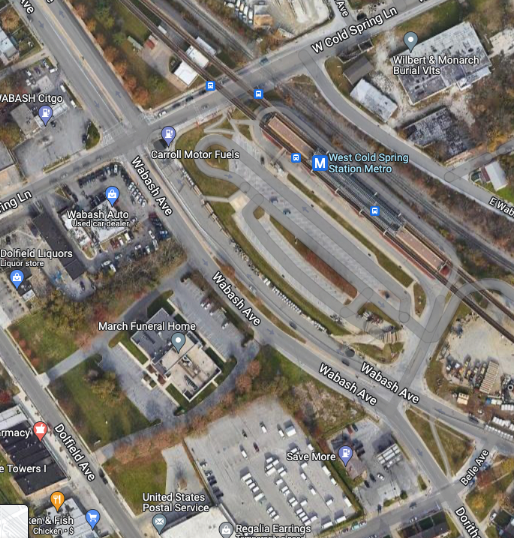

I used to live in Baltimore, which has a single subway line that connects the northwest suburbs to downtown. Which seems great until you visit the stations, which all look like this:

Baltimore built a great rail network, and then chose to put a giant surface parking lot at every station. While it’s great for a few people who want to live in the suburbs but have to work downtown,very few of the stations are located in places where people want to spend time, mostly because you have to walk, bike, or bus through an ocean of parking to get anywhere. (In case it’s not obvious, of course people need to park at these stations. We should build multi-story parking garages and housing on these sites, so people can drive to the station or, if they want, live next to it).

Transportation planning doesn’t work without land use planning, and most places do better on the former than the latter. Even in Chapel Hill, we have park and rides like Eubanks Road, which until recently had no nearby amenities. Now with Carraway Village, residents can live there and take the bus downtown, or people can come out there to eat at a restaurant.

What about highway spending? We can’t wait for transit!

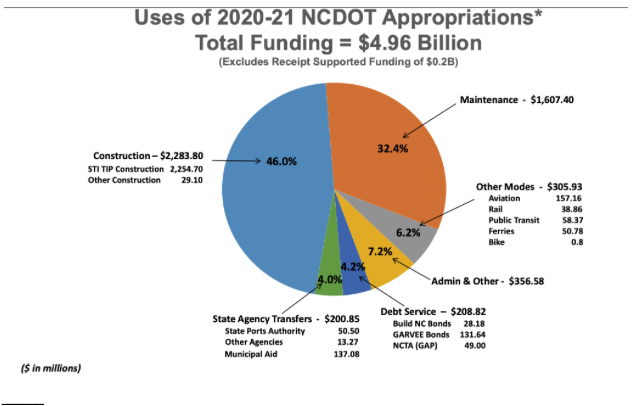

We should apply the same criteria to highway projects, which are even more wasteful than transportation projects. But look at the budget for the North Carolina Department of Transportation:

Of an almost $5 Billion budget, the DOT spends almost half of it on building new roads, a third on maintaining existing roads, fifteen percent on administration and debt service, and just barely six percent on all other transportation, a figure that includes aviation and ferries to coastal islands.

Should this change? Absolutely. Will it change in a gerrymandered state in which almost everyone who votes drives everywhere? Unlikely. (If you want to see what NCDOT is planning for the next decade and register your disapproval, they’re taking public comments right now).

What advocates can do is demand that the money that is spent on the things they care about is spent wisely. Mistakes are extremely costly, in terms of both time and money.

This is why it’s important to examine plans critically. Is it a good project? Will it serve enough people? Is it worth the cost? Is it politically feasible? Is it part of a larger vision?

The agencies trying to plan our future transportation infrastructure are making their best efforts. But there are many challenges to building non-auto oriented transportation in the state, and it’s easy to give in to supporting plans that look promising, but fail to meet one or more of these criteria.

Advocates and elected officials need to build support for good plans, and be willing to challenge bad ones. Otherwise, we’ll have a future much like the past, full of promises, few of them realized.