Background: On July 6, 2021, a structural fire damaged a single-family, four-bedroom home at 106 Kenan St., which was occupied by four college students (who thankfully were able to escape the fire without injury).

Last fall, the house was torn down, leaving an undeveloped .22 acre (9,579 square feet) lot in downtown Chapel Hill.

The proposal:

Land is scarce in downtown Chapel Hill, and vacant land is even scarcer. And, yet, the town’s land use rules, including those in the historic districts, make it difficult to build the housing that we need on this site or others like it.

In order to illustrate this, we wanted to imagine what this project could be if only we changed our restrictive land use rules. (No one associated with Triangle Blog Blog has a financial interest in this project. We just want more people to live closer to downtown, particularly if they can then commute by foot and bike to their classes or their job).

In order to show how this works, we’ll consider three scenarios, illustrating how rules set by the town of Chapel Hill limit what can be built in our community. We’ll start with the status quo, and then consider two other scenarios that might be possible if we changed our rules.

What could be built on this property that meets existing requirements, including its inclusion in the historic district?

Most likely, whoever builds something on this property will seek to build something that meets all current zoning requirements to avoid a costly and cumbersome rezoning process. (For more on the intricacies of zoning, see our writeup here). This project is zoned TC-2, which means that it must comply with the following standards:

- No street setbacks

- 15 feet minimum lot width

- 44 feet, building height-setback, maximum

- 90 feet, building height-core, maximum

- 1.97 floor area ratio, maximum

At the same time, it’s in the historic district, which imposes a requirement that any planned development receive a “certificate of appropriateness” from the town manager (3.6.2.d). Here’s the relevant section:

No exterior portion of any building or other structure (including masonry walls, fences, light fixtures, steps and pavement, or other appurtenant features), or any above ground utility structure, or any type of outdoor advertising sign shall be erected, altered, restored, moved, or demolished within the historic district until an application for a certificate of appropriateness as to exterior architectural features has been approved. For purposes of this article, “exterior architectural features” shall include the architectural style, general design, and general arrangement of the exterior of a building or other structure, including the kind and texture of the building material, the size and scale of the building…

In order to comply with “the size and scale” of the historic district’s buildings, a developer would be very likely to propose the following, in order to maximize the likelihood of approval for construction.

This was what existed before the building was torn down. At the time of the fire, four people lived in this house, and we expect about the same number of people would live in the new house.

What could be built if this project were not in the Historic District, but still zoned for TC-2?

This project is on the edge of the historic district, and, in fact, is the only one on the block that’s zoned TC-2 while also being in the district. What could be built if the town agreed to remove this lot (which can be done) from the historic district?

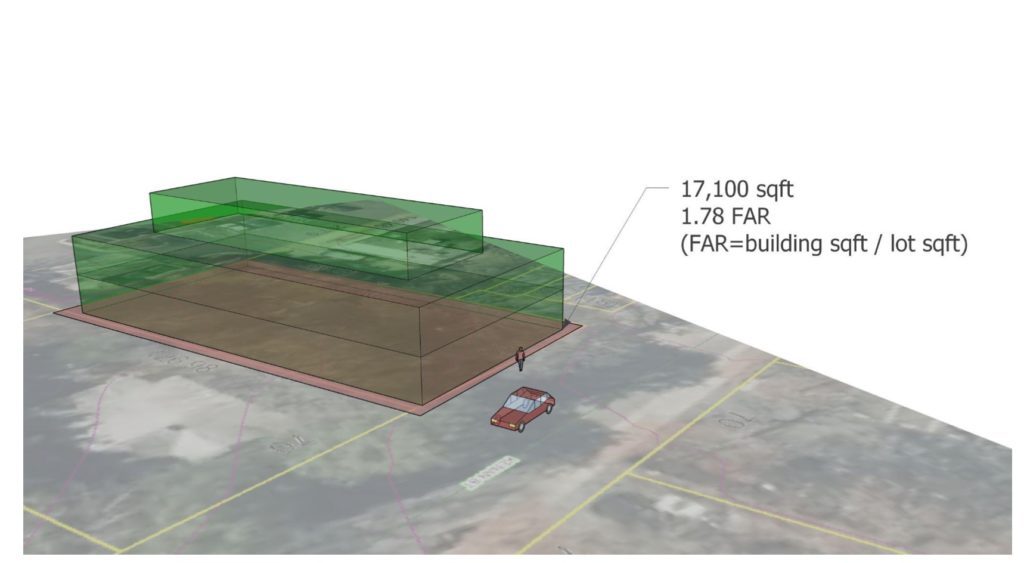

A developer could propose a residential building that maximizes the use of the lot, while still complying with height and Floor Area Ratio Requirements.

Unfortunately, the project likely couldn’t be realized, in part because TC-2 is a zoning designation best suited for larger parcels. One of the main reasons you see so many vacant lots downtown is that it’s impossible to build housing on them given current zoning regulations. For private developers, the concern is whether a project will “pencil out,” meaning that after one pays for construction costs, development costs, etc., they will still be able to sell the property at a modest profit. For nonprofit and government developers, the same calculus applies (except for the modest profit part), as it doesn’t make sense for anyone to spend more money building housing than the housing is worth.

With the FAR limitation of 1.97, the developer couldn’t maximize the use of this lot. They might only be able to propose a dozen units of housing, which wouldn’t justify the costs of developing the building.

What could be built if there were limited zoning restrictions?

What project might be likely to “pencil out” in the absence of onerous zoning restrictions, based on current land prices, construction costs, rents, etc?

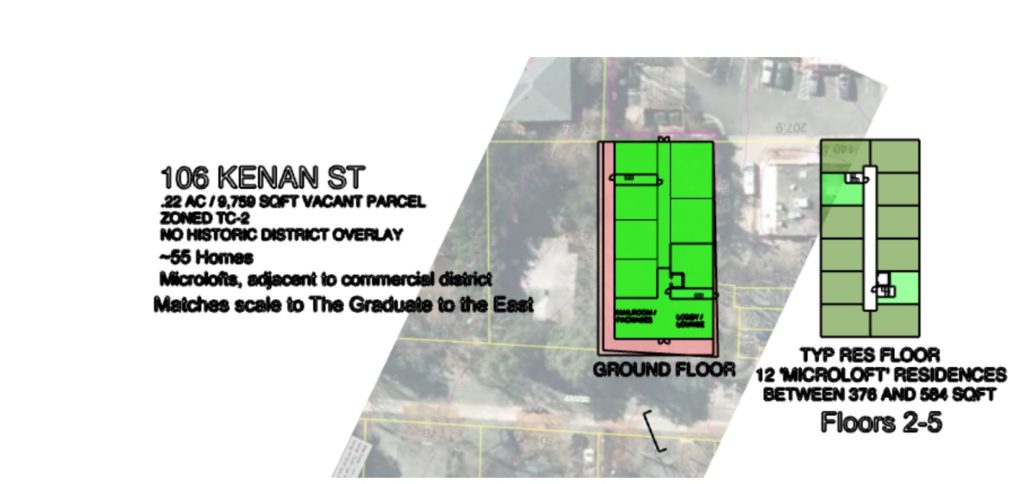

A much more ambitious project. Instead of a single-family house, a developer—either a private builder or a nonprofit—could build 55 microlofts, with a building that would be the same height as The Graduate Hotel that’s literally across the street. Each apartment would be between 379 and 584 square feet. There are very few studio and 1BR rentals in downtown Chapel Hill, so this project would fill a vital need. While we can’t predict what these units might cost, it’s reasonable to expect that they will be among the most affordable apartments downtown. And, creating more housing options would likely reduce the rise in rents elsewhere in our community.

Are other places building projects like this?

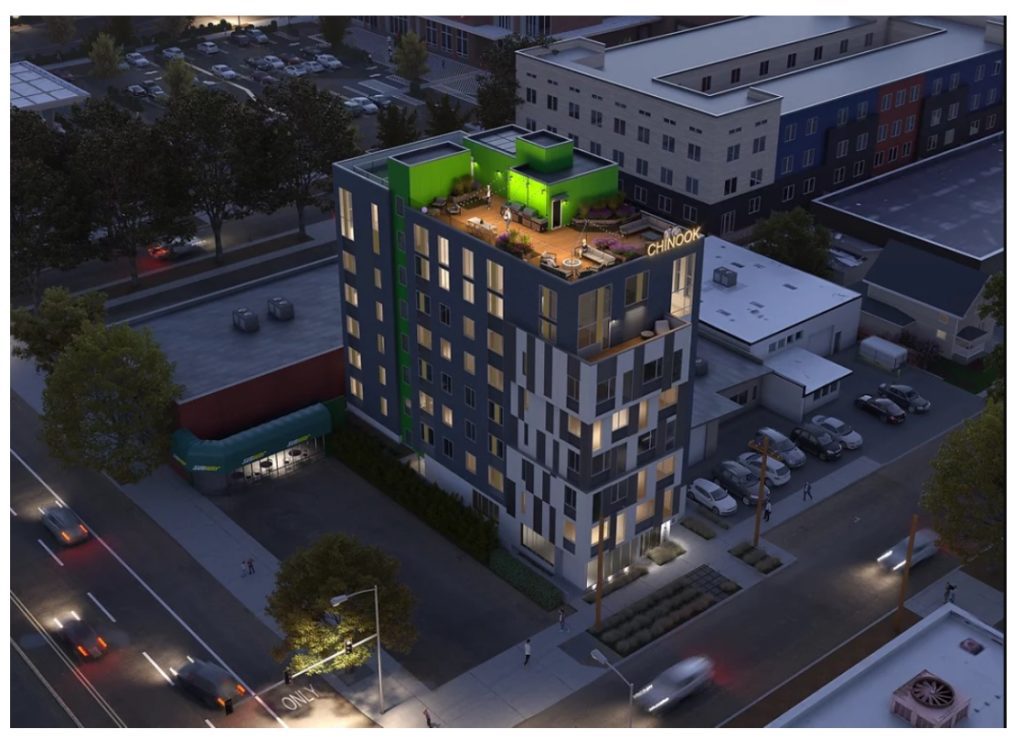

Firms such as N5 Architecture in Seattle specialize in transforming small urban lots into reasonably-priced multifamily and commercial space–which is sorely missing from Chapel Hill.

Their proposed project at 1446 NW 53rd uses a lot half the size of 106 Kenan Street to create 59 homes.

While you might think that this is something that only works on the West Coast, or in big cities, we only have to look to Asheville, where there will soon be an 80 unit apartment building on a lot that’s smaller than 106 Kenan, to see what’s possible.

And, while living in a studio isn’t for everyone, we suspect anyone who lives in Chapel Hill can think of 55 people they know who would rather live in their own apartment than have to put up with a roommate. (Nothing against roommates, but it’s nice to have your own space).

Why do this?

Suppose I were to tell you that there was a way to reduce rent increases, support the local economy, and protect the environment—for free. That’s this project. If we removed 106 Keenan from the historic district, and removed a few unnecessary zoning rules, we could build almost as much housing on this single property as exists on the entire block. (By our count, there are 51 bedrooms on the 100-block of Kenan Street, five less than we’ve proposed building here).

And, of course, if we allowed people to build on other lots on this block, we could add a lot of housing downtown, which would reduce the likelihood of property owners clearcutting land in Chatham County to build developments like this:

This exercise shows why the type and quantity of housing in Chapel Hill is determined by factors that are largely within control of the town. If we want a future of housing abundance and a walkable town, we need to find a way to make it easy for properties like 106 Kenan to be redeveloped.

If, instead, we choose to keep current land use restrictions in place, we’ll continue to see a lot of vacant and under-used land downtown. New large-scale developments will be met with considerable resistance and, even if they’re approved, will only be affordable to high-income people.

Too often, when people complain about politics, they’re told to vote. A better solution is to get involved in local government, who make decisions on the some of the most critical issues we face—where we live, how get around, and who can be our neighbor. Contact the Chapel Hill Town Council and let them know that you support land use reforms that will make it easier to build housing in and near downtown.