This is the first post in our Harder Truths series.

Starting in the 1960s, so-called historic districts—neighborhoods deemed to be “significant in American history, architecture, archeology, engineering, and culture”—were created in U.S. cities and towns to place further restrictions on development. Although these districts were supported by federal legislation, local and state governments were given most of the power to prevent buildings from being torn down or altered.

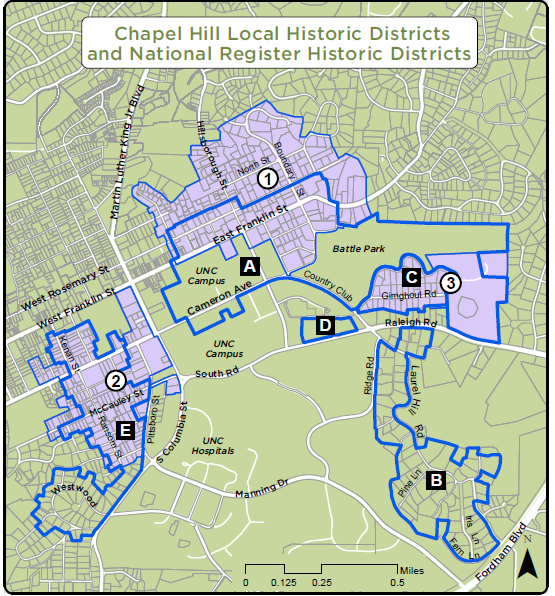

In 1971, North Carolina passed legislation allowing local governments to create locally designated historic districts. Five years later, the Town of Chapel Hill created its first local historic district, the Franklin-Rosemary Historic District, covering the neighborhoods immediately adjacent to downtown Chapel Hill. In 1990, the town designated another large local historical district, Cameron-McCauley, which covers the neighborhoods to the east and south of Columbia Street. Four years later, the town created its third historic district, Gimghoul.

While local historic districts can be a useful tool in some instances—North Carolina’s original legislation was intended to protect the actually-historic neighborhood of Old Salem—in Chapel Hill they effectively function to make our community more exclusive and less vibrant.

If Chapel Hill is serious about building a more equitable and dynamic community, we need to talk about reducing the size and scope of our historic district. Here’s why:

Chapel Hill’s historic districts aren’t really about history. Instead, they’re bizarro HOAs on steroids.

If you spend any amount of time reading about Homeowners’ Associations (HOAs), you’ll probably come across any number of nightmare stories. The domain of rule-sticklers and petty tyrants, HOAs keep people from painting their house with interesting colors, building tree houses in their backyards, and planting pollinator gardens.

Houses in Chapel Hill’s historic district are overseen by a special body, the Historic District Commission, which passes aesthetic—and all kinds of other—judgments on things people might want to do with their property.

Armed with a “certificate of appropriateness,” the Historic District Commission can allow, or stop, a property owner from doing almost anything on their land that impacts the Historic District’s guidelines. Unlike most historic districts, Chapel Hill’s isn’t primarily concerned with preserving the history of the built environment, as there are not that many old buildings to preserve. There are entire neighborhoods in the historic district that were built after it was designated.

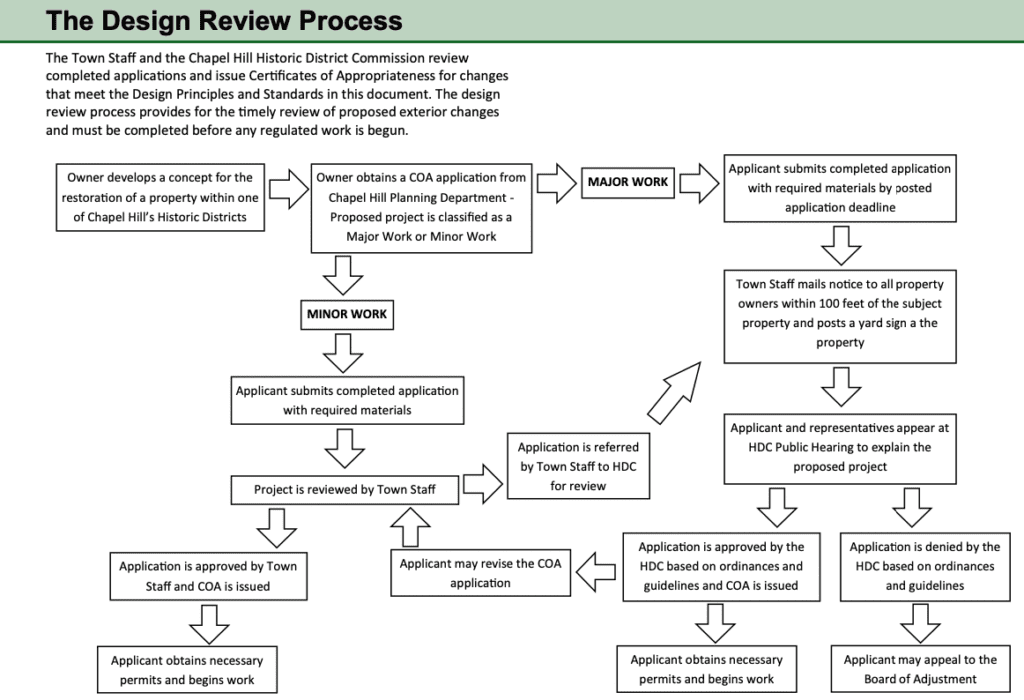

Instead, Chapel Hill uses it primarily to limit what can be built near downtown. Last year, the Town published a 180-page book on the design “principles and standards” for buildings in the historic district. Anyone wishing to alter their property in the historic districts must follow this chart:

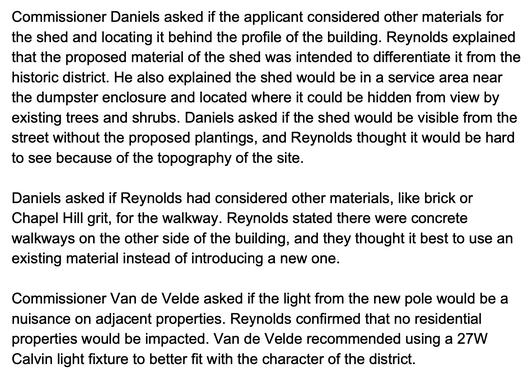

As you might expect, a complex process makes it easy for HDC members to let their own opinions control what can be done in the historic districts. If you read the minutes of any HDC meeting, you’ll come across items like this (from their July 2022 meeting):

If you’ve dealt with an HOA, you might not be surprised to learn that there’s someone out there who has ideas about what light bulb you should use to illuminate your new deck. But, the fact that there’s a whole committee of these folks—with town staff support and legal standing—to exact judgments on your new twinkle lights on your back porch should give you pause.

The historic districts make living near UNC all but impossible for staff and graduate students.

Imagine for a moment that we eliminated the local historic districts entirely. People like old houses, and many of the houses in the historic districts couldn’t be built today because they violate one of dozens of current land use requirements. (Related: Our series on zoning regulations in Chapel Hill.)

However, throughout the historic districts there are also a lot of new houses, from cheaply built ranches from the 1950s and 1960s to poorly maintained rental properties. Some of them are on pretty big lots. You even have a few big parking lots in the district that could easily be turned into something more useful.

By making it next to impossible to add housing near downtown Chapel Hill, we drive up the cost of housing for miles around the university, home to tens of thousands of students and almost ten thousand employees. Instead of getting vibrant walkable neighborhoods filled with people of all ages and backgrounds, we get a lot of large houses that are seasonally occupied. If you walk through the historic districts in the summer you’ll notice that a lot of the homes are empty. The undergraduates who live in fraternity and sorority houses are back home, and the owners of million-dollar properties have enough money to escape the heat and humidity of Chapel Hill summers.

If you visit places that are truly historic — Old City in Philadelphia, the North End in Boston, Fell’s Point in Baltimore, and downtown Savannah — you’ll see new buildings mixed in with the old, each making the other look and work better. Instead, by defining our historic districts as what people thought was good in the 1970s—lots of space for cars, not so many people—we’ve created something that doesn’t work for anyone. As the Daily Tar Heel’s Michael Beauregard observed in an op-ed last year, the historic districts prevent people from building so-called “missing middle”housing near downtown, buildings that fit ”between the goliathan student housing projects we have seen so far and the low-density single-family homes that make up a significant portion of Chapel Hill’s housing stock”

The neighborhoods in the local historic districts aren’t even that historic.

On Franklin Street, there’s a historical marker celebrating University of North Carolina (established 1795) as the first public university in the nation to “open its doors,” a technicality that allows the university to claim that it is older than the University of Georgia, which was chartered four years before UNC (1785 vs 1789).

The Town of Chapel Hill was founded in 1792, and from the beginning was intended to serve the university. The university and town celebrate its ties to the 18th century, both symbolically, in the Old Well logo, and in its attention to the creation and maintenance of historic buildings. Eight buildings from the University’s first seventy years, many built and financed with the labor and bodies of enslaved people, still stand.

In 1971, the same year that the state legislature revised its historic preservation act, UNC’s North campus was designated as the Chapel Hill Historic District. This was an implicit acknowledgement that most of the buildings in Chapel Hill that are historic are on campus.

As soon as you leave North campus, there are very few buildings that date from the 19th century. This is in part due to the fact that the university and the town did not grow very much for its first 125 years.

As late as 1900, Chapel Hill reported just 1,099 residents, in a county with less than 15,000 residents (the state’s population was almost two million). There were dozens of towns in the state that reported several thousand residents that year, and coastal towns like New Bern had nine times as many residents as Chapel Hill.

While Chapel Hill did begin adding residents in the 20th century, even much of that growth happened after World War II, when the G.I. Bill brought thousands of students to campus and the modern research university was created. For example, North Carolina Memorial Hospital, the first building in UNC’s Medical Campus, didn’t open until 1952. Chapel Hill’s population didn’t cross the 10,000 mark until 1960.

Although annexation explains some of the town’s rapid growth, Orange County’s population didn’t reach 100,000 people until 2000, long after Durham, which got there fifty years earlier. A recent study found that just three percent of the homes in Chapel Hill were built before 1930.

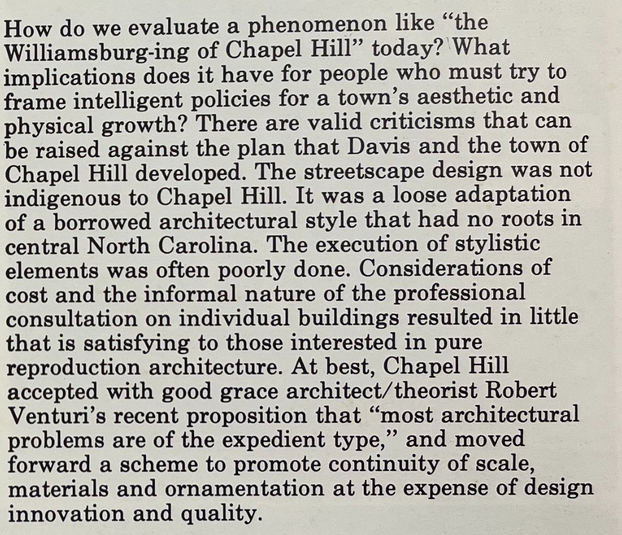

Instead, the notion that the town of Chapel Hill is a historic place is a fiction, created in the 1950s at the behest of town business people. (Whenever you hear old-timers discuss the “Village” of Chapel Hill, this is what they’re referring to). In a 1975 article, Diane Lee, then the editor of the quarterly newsletter of the Historic Preservation Society of North Carolina, notes that Chapel Hill business leaders made a conscious effort to promote Colonial architecture downtown in a mostly failed attempt to make Chapel Hill look like a “real” historic place, like Colonial Williamsburg. Cheered on by the editor of the local newspaper, Chapel Hill tried to copy other communities, with predictable results.

Bob Stipe, a former UNC professor who led the creation of Chapel Hill’s historic districts, admitted in 1982 that our town’s historic districts are unusual because they’re not actually about preserving historic structures.

Our historic district boundaries are steeped in Chapel Hill’s racism.

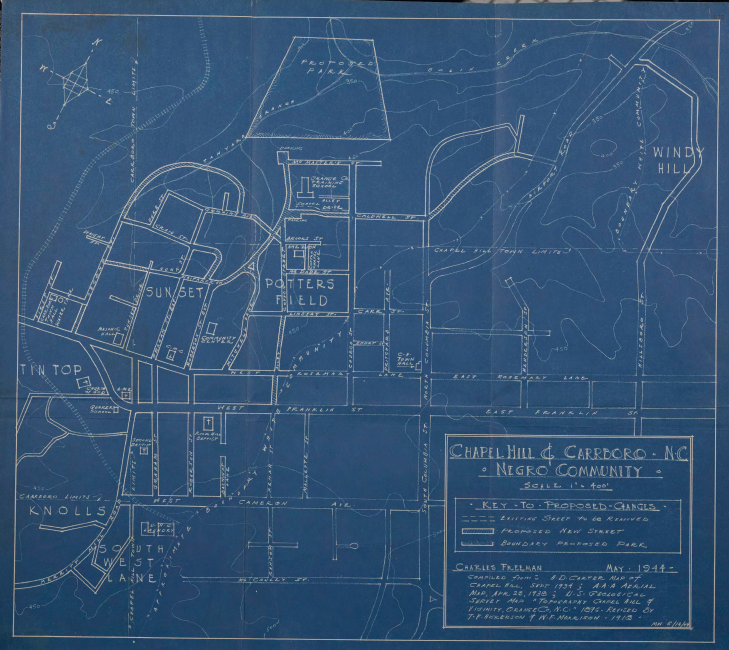

In 1944, Charles Freeman mapped out Chapel Hill and Carrboro’s segregated Black communities as part of his master’s thesis. Here’s what the map looked like:

As Mark Chilton notes in his excellent blog post, “Freeman’s color segregation line was largely still the case into the 1990’s.” And the line largely lines up with our current historic districts.

We can do better. By reducing the size and scope of the historic districts, we can create a diverse, inclusive, and thriving downtown Chapel Hill.

Here are steps we can take to reform them so we can move forward as a community.

Whenever possible, shrink the footprint of the historic district.

It is possible to remove properties from a historic district. We can start by removing properties that are near downtown, such as those on Kenan Street. By starting with a small area, we can identify the strengths and weaknesses of the historic district, and then make decisions about what to do with properties further away from downtown later.

Make the historic district commission more inclusive.

Currently, there are 9 seats on the historic district commission and all members must reside within the planning jurisdiction of Chapel Hill. Because these terms are three years, there are very few students—who make up a large percentage of the residents in the districts–who serve on these commissions. We should consider adding a one-year student seat to the commission, and the town can work with UNC’s student government to ensure that there is someone to fill the position.

Tell the truth about the historic districts.

The Town of Chapel Hill’s 2021 document on the Historic District opens with the following paragraphs:

Such language implies that the neighborhoods around downtown Chapel Hill are essential to the town’s “character.” Instead, they ensure that the town, once known for its cultural vibrancy, will forever remain as it was in the mid-20th century. But when the historic districts were created, many residents questioned whether we needed the historic district protections, and predicted that putting them into place would limit the town’s potential to grow. Thirty years later, we’re all paying the consequences of their actions. (Carrboro wisely opted to not create a historic district, which is why you see new construction near downtown).

Instead of pretending as if the historic districts were passed down from on high, never to be touched or debated, the town needs to remind residents that the historic districts were created for specific reasons, and that the goals of those who created them might not align with ours. We cannot let the actions of past residents condemn our town’s future.