Along Elliot Road in Chapel Hill sits a modern rental apartment building called the Berkshire Chapel Hill. Though nondescript, several years ago this “luxury” apartment complex rocked Chapel Hill’s political landscape. In 2015, a new mayor and slate of like-minded Town Council members won election following community outrage after the Berkshire replaced a perfectly nice asphalt parking lot.

Nearly seven years after this project was approved, and with hundreds of new residents now able to live in Chapel Hill, some Chapel Hill activists continue to defend our town from new residents. The latest is a piece by a long-time Chapel Hill volunteer, activist, and member of the anti-growth organization Chapel Hill Alliance for a Livable Town (CHALT). She says, as CHALT has for many years, that we’re all full and don’t need anyone else.

The point is made clear in the first paragraph, where she notes that the new owner of property in town may be planning “more market-rate apartments.” That, she exclaims, is “Just what Chapel Hill does not need!”

(Let’s ignore “does not need” for now. We’ll get to that later.)

She points out two new projects under development. One is a Town plan to allow moderate-density housing on land on the north side of Town. The second is a private proposal to build a multistory condominium building (including a few deed-restricted affordable units) with ground-floor retail along the main southern corridor into Town, a short walking distance from the UNC medical campus.

These projects are bad for the Town, she says, because this increased density means “town control decreases and our cost to maintain town services increases.” It’s not clear what she means by “town control decreases” (perhaps she’s concerned the future residents may not share her views on local issues) but her next sentence is the crux that animates so many of these discussions: “If the new residents moving here live in apartments, they don’t pay residential property taxes, but do continue to drain our budget coffers for services.”

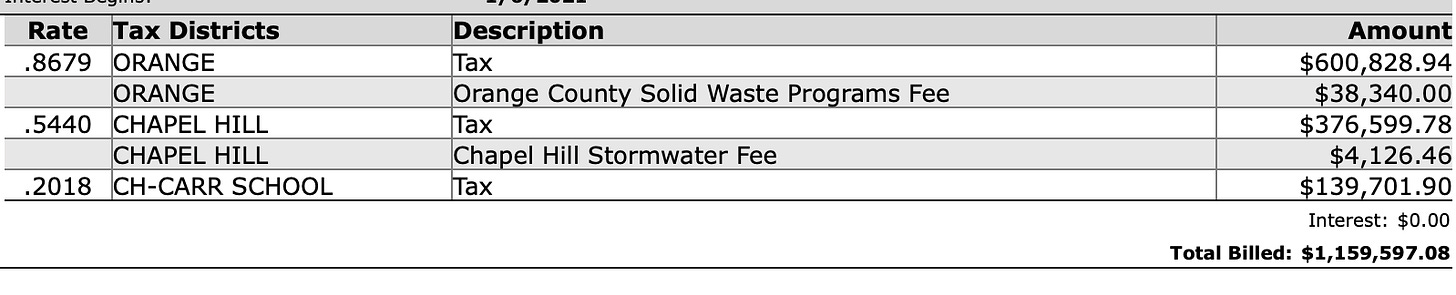

That point is, quite simply, not true. Who’s not paying residential property taxes? The Berkshire, which houses hundreds of residents, pays a hefty property tax bill of more than $1.16 million, including more than $139,000 in school taxes — which does not even count the money that is paid to the county and that the county directs towards schools.

The much-maligned Lux/Lark apartment complex, which is aimed towards students, paid more than a half-million dollars in property taxes. That includes $63,440 directly to the school system — taxes paid through the rent of college students who are unlikely to have children in our public schools. These residents also pay sales taxes, and they’re more likely to spend money in Orange County if they live in Chapel Hill than if they live, say, in Fuquay-Varina.

There’s no doubt, as the author notes, that all else being equal, more housing and more people requires more services — new fire trucks and ambulances, keeping roads in good repair, garbage and recycling, and so on. But not all development is equal. The cost of services like garbage collection and maintaining roadways depends on how we develop.

Compact footprints, like multi-family apartments, offer many service efficiencies. The Berkshire apartments didn’t add a single additional foot of street for the Town to maintain. A comparable road in town that serves about 32 single-family homes and one small apartment complex will cost taxpayers $200,000 to repave next year. For the Berkshire, our local water and sewer agency didn’t need to add a single extension to our water and sewer system. It’s much more efficient for a garbage truck to service hundreds of residents at a single dumpster than to drive through single-family subdivisions stopping at every driveway. So if we care about costs of services, we really should be advocating for more denser residential development.

We live in a thriving region. While some may prefer that we follow the trend of a midwestern Rust Belt town with a stagnant or shrinking population, we are growing. People want to move here. If we want to stop the cost of housing from skyrocketing, we need to make sure that people have safe and healthy places to live. The new apartments around town offer that opportunity for many, particularly young single people and couples just starting their careers. Think of the UNC grads who typically depart for Durham or Raleigh after graduation because they want to stay in the area but couldn’t find any place to live in Chapel Hill.

If Chapel Hill doesn’t allow moderate-density residential growth, it’ll take place in northern Chatham County and southeastern Durham County and Wake County, in sprawled development patterns that are much costlier to service. These sprawled developments also have much more significant environmental impacts, affecting much more land and encouraging much more driving that an apartment building right near UNC. We may see their cars on our roads, but we’re not going to have their property taxes, or as much of their sales taxes, or their civic involvement.

If Chapel Hill doesn’t allow residential growth, the Town will be throwing away money we’re spending to try to revitalize our downtown. The Town just dedicated more than $30 million towards a brand-new parking deck to spur office development downtown, and we’re hoping to invest millions more (and convince the federal government to invest tens of millions) in a bus rapid transit system. If we want our efforts to encourage commercial development to be successful, we need housing close-by that makes it easy for workers to get to our commercial spaces.

If Chapel Hill “does not need” more apartments, why do so many developers want to build them? Why did the Berkshire fill up within a year of opening? Why does it remain nearly fully occupied (on its website today, 14 out of its 265 units are listed for rent)? Who is supposed to determine the “right” number of residences? There have long been complaints about student rentals near UNC — should we encourage young professionals and graduate students to live in single-family homes-turned rentals instead of apartments? Or, perhaps we should hire John Candy to stand out front and say “Sorry folks, Town’s closed.”

And yes, we do need more affordable housing. That’s why it’s great the Town is supporting and funding multiple affordable housing developments and strategizing how to help manufactured home residents stay in town. It’s puzzling how the Town’s efforts to increase affordable housing should mean no additional market-rate housing.

Here’s how the author ends her argument: “We now have thousands of market-rate apartments, some of which are empty, and ever-rising rental rates. Meanwhile, our costs to service the units accelerate.” Let’s unpack this. Imagine these market-rate apartments had never been built and we did not have any empty apartments. Where would the folks in the Berkshire be living instead? Where would they be working? Maybe the UNC grad students wouldn’t have attended UNC at all because of the difficulty finding housing, or perhaps they’d live in another home in Northside that was converted to student housing. Maybe the young students and professionals would be living in Durham or Raleigh and contributing to those communities. And, we wouldn’t have the millions of dollars in property taxes that the Berkshire, the Lark, and other multifamily pay every year.

It is a good thing we have many market-rate apartments and that not every one is occupied — it’s the only thing that kept Chapel Hill’s apartment market from overheating even more, after UNC’s shut-down of on-campus housing forced students to off-campus residences. There’s scant evidence that it’s making any cost of services accelerate. And I don’t think Berkshire residents have made Chapel Hill a less appealing place to live.

Chapel Hill needs more places to live so that we can accommodate all our future residents — everyone who wants to live here. We should invest in affordable housing, and we should allow market-rate housing. We should make it easy for UNC students to live and work and shop in town after they graduate. We should welcome everyone. Let’s keep building housing.