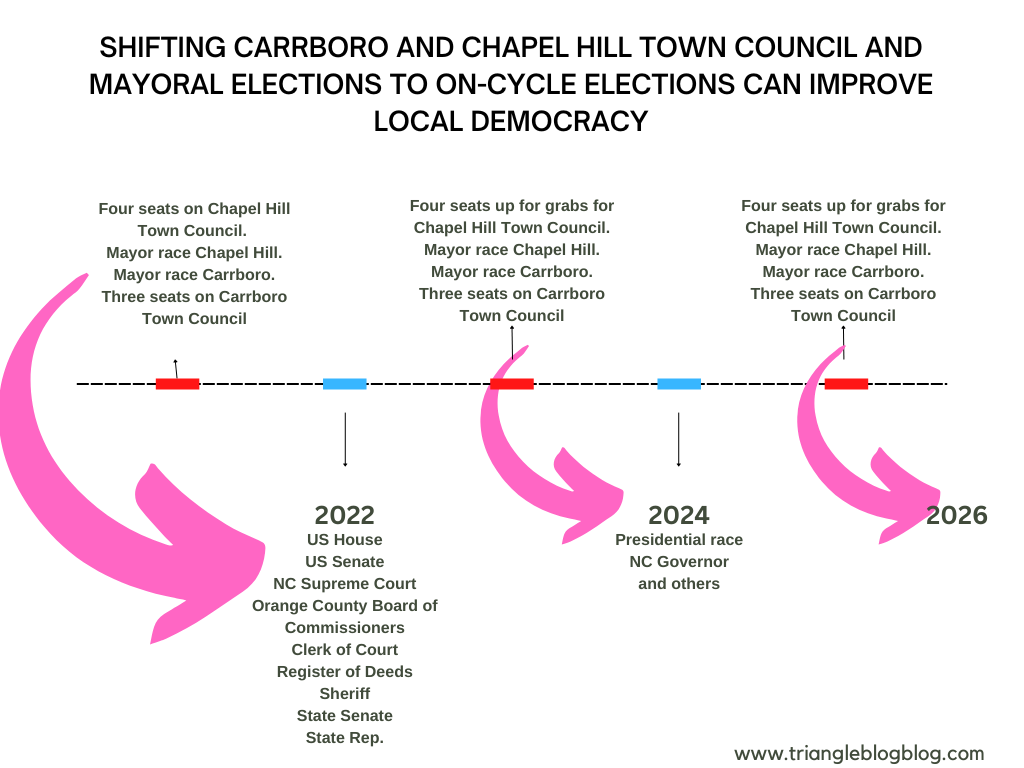

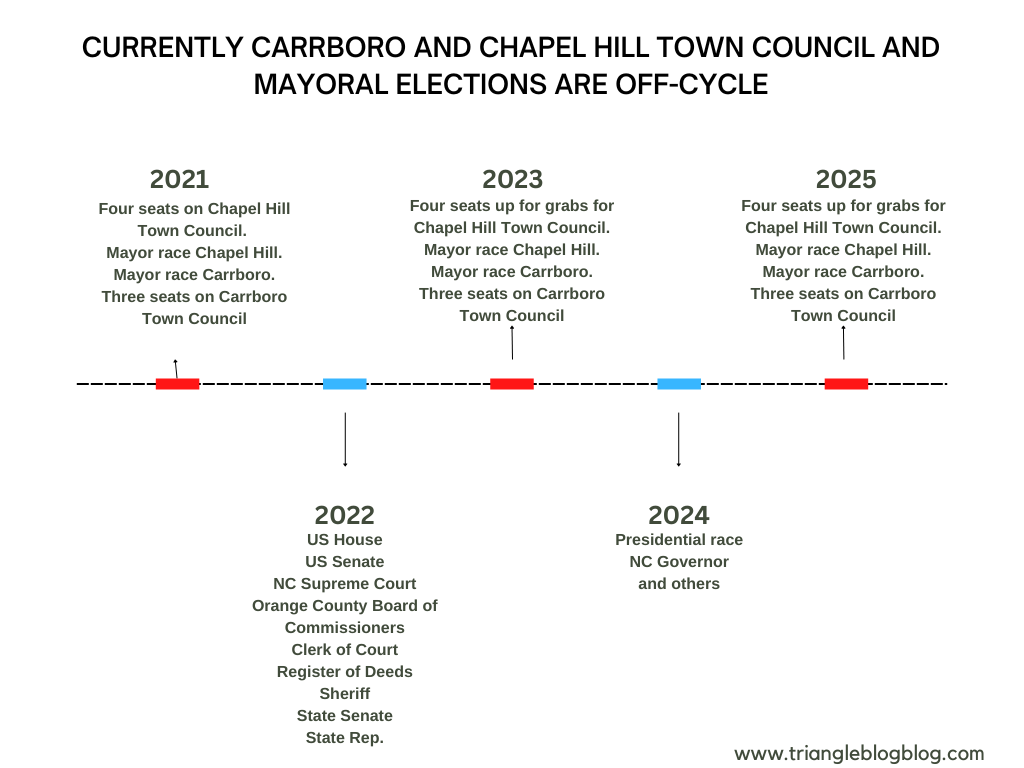

Most municipal elections in North Carolina are in odd-numbered years, which means they don’t line up with federal elections (held in even-numbered years) or state elections (also held in even-numbered years.)

This is starting to change, albeit slowly. Over the past decade, a number of municipalities in NC have switched to even-year elections: Winston-Salem, Asheville, Raleigh, Lincolnton, and all of the towns in Stanly and Surry Counties now hold their municipal elections in even-numbered yeras.

Why does North Carolina hold municipal elections in off-years?

It’s complicated. The writer Jeremy Markovich, who runs the excellent blog North Carolina Rabbit Hole, dove into the issue last year. We recommend reading his entire piece, which details how and why NC made this decision in 1971. (The best guess, from a School of Government professor named Robert Joyce, is because they wanted to make them “more pure” and separate them from partisan contests. They thought it would also lead to higher turnout in municipal elections.)

That didn’t happen. Off-year elections have much lower turnout across the state than races held in even years. And when municipalities switch their elections, turnout goes up by quite a lot.

This November, we’ll have a chance to test the effect of even-year elections locally. Last December, Carrboro’s Town Council voted to hold a special election this upcoming November to replace the council seat held by now-mayor Barbara Foushee. That means the election for the Carrboro town council seat will coincide with the elections for governor and president.

This is an exciting (and no cost) way to test out what even year elections might look like in Chapel Hill and Carrboro. Huzzah!

We’ve been curious about the possibility of Carrboro and Chapel Hill switching to even-year cycles for some time. Given that Carrboro will now “test it out,” it seemed like an appropriate time to reach out to Gerry Cohen, who is somewhat of a local election guru. Cohen has served as a member of the Wake County Board of Elections and is a former Chapel Hill Town Council member (from 1973-1979). He also has a deep understanding of election laws in North Carolina.

Our conversation took place over email.

Thanks for chatting with us, Gerry. First up, a practical question: What is the process for changing to even-year elections for a municipality that currently has odd-year elections? (How do you get approval to do it? How long does it take? How does it affect the terms of current members?)

Under current law any such change must be approved by the General Assembly by enacting a bill. There are about 60 that have already been moved to even year. Generally the town board would pass a resolution requesting the change, [and] typically such requests are honored. The earliest this could be taken up in the NCGA is the short session this April-July, or the 2025 session that starts in February next year.

The normal process of getting a local bill is for the governing board to vote on a resolution setting out the requested legislation then send the request to the house and senate members representing the area. Many times a local government with a legislative agenda might meet with the legislators. There is no statutory process for making the request

Most of the changes have involved extending all current terms by a year to get in-cycle. (thus if enacted early 2025 there would be no 2025 town election, the next after 2023 would be 2026.) A small number [of elected roles within municipalities] have had terms SHORTENED by a year. A couple have had the change starting on the second following election with the next odd-year electing members for one or three years

What is the likely turnout effect? (How different do demographics look in even-year elections? We assume younger people vote, but what about other groups?)

Looking directly at three municipalities [that switched]:

- Raleigh switched to even year in 2022

- Wake School Board switched in 2014

- Winston-Salem switched in 2016.

Turnout basically nearly tripled in the even year mid-term, and nearly quadrupled in the presidential. The increases are largely in turnout of renters, newer voters, younger voters and minorities.

Can you speak a little more to who turns out for even year elections?

Several research studies nationally have shown that the biggest turnout increases when elections are moved from odd to even years have been with renters, newer voters, younger voters and minorities.

Gerry provided us with the percentage of voters who voted in the last several cycles in Orange County. You can see a noticeable difference between odd and even-year turnout.

Orange County turnout (for -21 and -23 its the % of eligible voters in Chapel Hill, Carrboro, Hillsborough and CHCCS that voted)

2020 76.2% PRESIDENTIAL

2021 23.0% MUNICIPAL

2022 60.1% MID-TERM

2023 26.2% MUNICIPAL

Gerry also looked at the demographics of who turned out in those years.

Looking at age, I checked turnout in the UNC precinct for those four years. The UNC precinct includes all of university housing, and some residential neighborhoods south of Franklin St and east of Columbia St.

2020 37.8% (likely low because all but two dorms were closed due to COVID)

2021 12.2%

2022 40.5%

2023 20.1%

Thus for younger voters we see a substantial turnout increase in even versus odd years.

What have we learned from other towns that have switched to even year elections in NC?

What are the costs associated with such a change?

There is no charge to pass the bill! For the local government, generally when elections are moved from odd to even year it costs the local government less than half what it had been paying. The exact calculations depend on the formula the county uses for cost sharing with municipal elections, which varies. Complicating things, if just Chapel Hill changed – leaving Carrboro and school board in odd-year – their costs to continue on odd-year could increase.

(Note that if school board election was moved, it could go to the even year primary to be at the same time as county school board. Orange County school board changed to even-year nonpartisan primary in either 1970 or 1972. It was partisan 1964-70. Before that it wasn’t elected at all, it was appointed by the NCGA!!)

Why does NC have even year elections?

Gerry pointed us to the Jeremy Markovich story, which he says is “directly on point and well researched.”

Anything else you want to mention?

A common criticism of holding even-year elections is that “town election will get submerged in national issues and people won’t pay attention to local races” I think this is bogus. County commissioner elections have been even year for at least a century.

It is true that about 10-12% of voters will leave the town race blank, but my triple/quadruple totals above are those who actually cast a ballot for the town race and marked a candidate. Right now 80% of voters ignore the odd-year election!

My Raleigh experience in even year was that there was actually MORE attention paid to the local race in even year, more campaign forums etc. In addition when municipalities changed to even years, town candidates don’t have to run GOTV efforts. I don’t subscribe to “the voters are too stupid to vote in even years” theory. It’s actually easy to find the town races because state law provides that they will be the very last thing on the ballot (though above any referenda) so it’s easy to tell voters how to find the town race!