The Chapel Hill Historic District Commission (HDC) focuses on the tiny details. If you’ve been to a meeting, you know that it’s an opportunity to spend an evening futzing over the minutiae of fence heights and lighting elements and window trim with people who have the authority to force you to spend tens of thousands of dollars to meet their unyielding requirements. Working with the HDC to make improvements to your home is a bit like working with an interior decorator, but if that decorator’s specialty was high-end torture chambers.

On Tuesday, May 9, the HDC’s meeting was an opportunity to revisit the town’s Housing Choices for a Complete Community text amendments, or, as it’s more commonly called, the proposal to build “missing middle” housing types throughout our community. In early April, town staff announced it was dialing back its original proposal – it would now allow for duplexes throughout town, but limits the construction of denser housing to places where they’re already permitted.

The watering down of the proposal was in part in response to vociferous complaints by mainly older, wealthy white homeowners, and especially those residing in Chapel Hill’s historic districts – home to some of the most expensive real estate in North Carolina. (As Delores Bailey, director of the local affordable housing non-profit EMPOWERment, Inc. observed in a recent discussion, low income people and people of color haven’t been nearly as successful in advocating for themselves over the past decades as wealthy white homeowners have been in just the past few months).

While town planners Anya Grahn‐Federmack and Tas Lagoo gave a version of the same presentation they’ve delivered a dozen times or more, they added a few new slides that show how the revised proposal, which allows for duplexes, will work in practice.

Not surprisingly, the Historic District Commission, which, as we’ve discussed previously, is essentially a design review board for neighborhoods near campus, is opposed to the changes. In fact, several times during the meeting the commissioners members went beyond their remit to complain about other parts of town outside of the historic district (like Blue Hill, built over the past 8 years) and offer advice about how the town should proceed.

One particularly entertaining moment came when a commissioner suggested that the town embark upon a “pilot project” in one neighborhood. “You mean in the historic district?,” another commissioner asked. “No, of course not. The historic districts should be exempt,” came the reply.

At the end of the discussion, the HDC resolved to form a committee to prepare recommendations to the town council, which would explain why they believe the historic districts should be exempt from adding any missing middle housing to lots within the local or national historic districts. (Of course, they would never think to try to stop people from building new $3M single family homes in the historic district.)

As one might expect, HDC members noted the value of having old houses in the neighborhoods around campus, suggesting that they make Chapel Hill what it is. And if we were discussing a living history museum, like Old Salem or Colonial Williamsburg, that draws tourists to see the olden ways of everyday tasks like cooking food, making clothes, and caring for livestock, the HDC might have a point.

But, as the people who created the historic districts knew, for the most part the homes in the historic district are not that architecturally distinct, and not that old. Many of them were built after 1930.

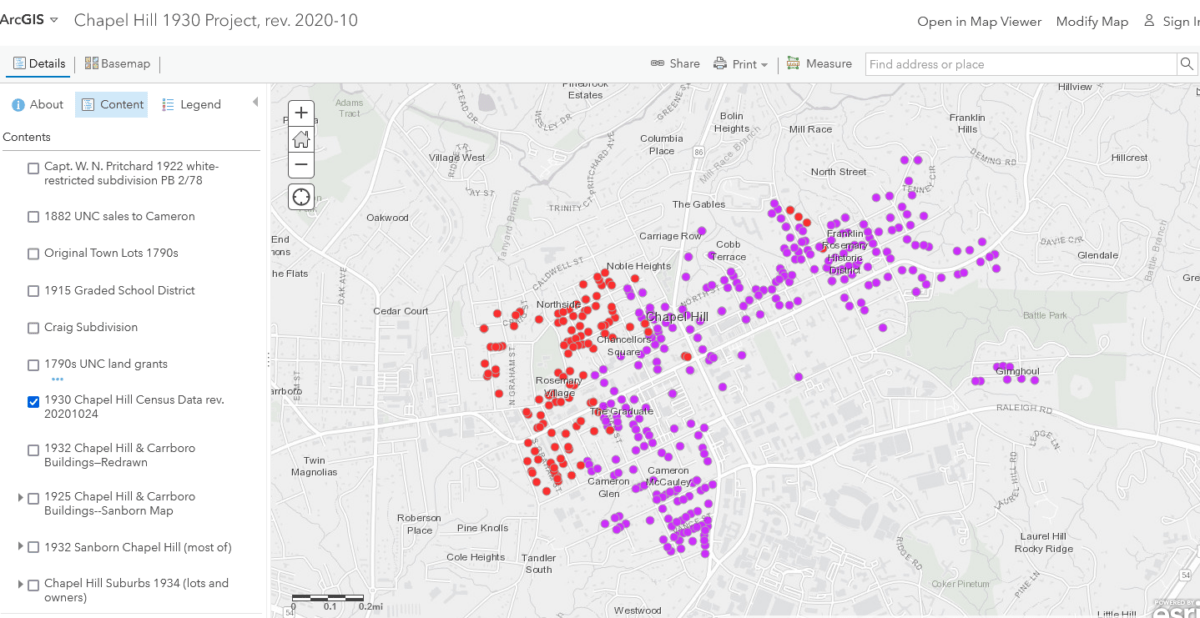

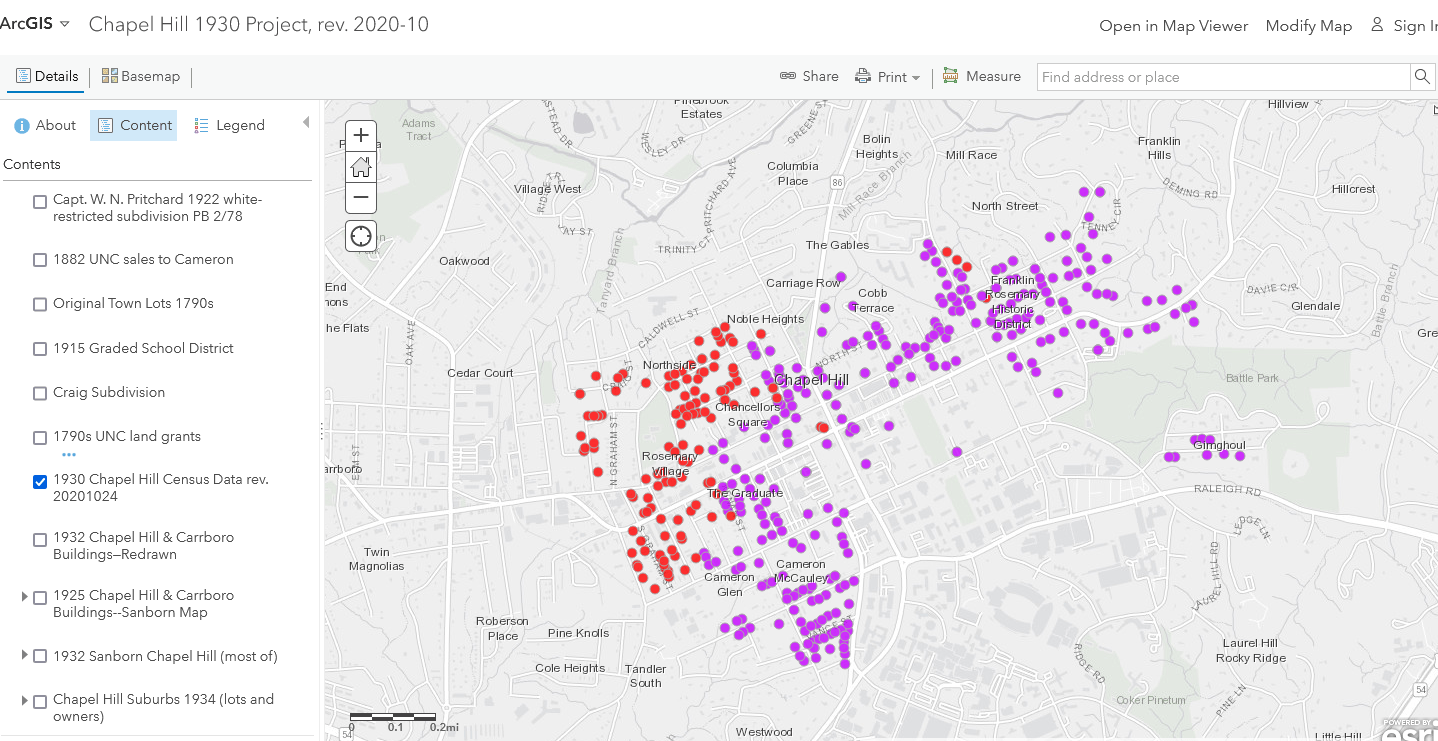

Nor were they limited to single families. Many of the larger homes were used as boarding houses, and some were even converted into single-family homes with the support of local historical preservationists. Census data shows that roughly 1 in 5 of the homes shown in the map above rented rooms out to one or more boarders in 1930. Many of our historic district houses were, historically-speaking, multi-family residences.

The 1930 Census shows that professors and students and UNC support staff and barbers and bookkeepers lived in these neighborhoods. If we really want to honor the history of these neighborhoods, what better way to do that than to enabled the types of people they were designed for to live in them again?

In an answer to a commissioner’s question about why the town council was so concerned about making it easier to build housing in town, planner Tas Lagoo paraphrased a section from a speech given by the American television broadcaster, and UNC alum, Charles Kuralt in 1993, as part of the university’s bicentennial celebrations:

What is it that binds us to this place as no other? It is not the well or the bell or the stone walls. Or the crisp October nights or the memory of dogwoods blooming. Our loyalty is not only to William Richardson Davie, though we are proud of what he did 200 years ago today. Not even to Dean Smith, though we are proud of what he did last March. No, our love for this place is based on the fact that it is, as it was meant to be, the University of the people.

Since its creation in 1976, the HDC has carried out the solemn work of maintaining architectural and landscaping standards associated with the Chapel Hill of Charles Kuralt’s youth (Kuralt attended UNC in the 1950s). But it’s the Planning Commission, and, even moreso, the town council, that are charged with focusing on the town’s future.

Should we exempt the Chapel Hill neighborhoods that are closest to campus from even playing a minor role in housing the university’s students and teachers? Can Chapel Hill be a town of the people if it closes its doors to those who don’t have the money and desire to live in a theme park version of the 1950s, when the neighborhoods around downtown were white-only, by practice if not by law? Are we really more concerned about the color of the hinges of a gate than we are whether it can be opened wider so more people are able to join our community?

This is the question before us this month and next (the Planning Commission will consider the proposal on May 16, and offer its recommendations. And,on May 24, the Chapel Hill Town Council will open its hearing on the proposal at a meeting we expect to draw significant interest). We can either make modest changes to our neighborhoods to accommodate a growing state and region or we can sit by while our neighborhoods become ever wealthier and isolated from the university and our state. If we follow that path, we’ll be honoring the worst parts of our history, not the best.

While the HDC might want to exempt itself from missing middle housing types, none of us get to exempt ourselves from the reality that we need to look at the bigger picture and build a Chapel Hill for all.

Stephen Whitlow and Melody Kramer contributed to this piece.