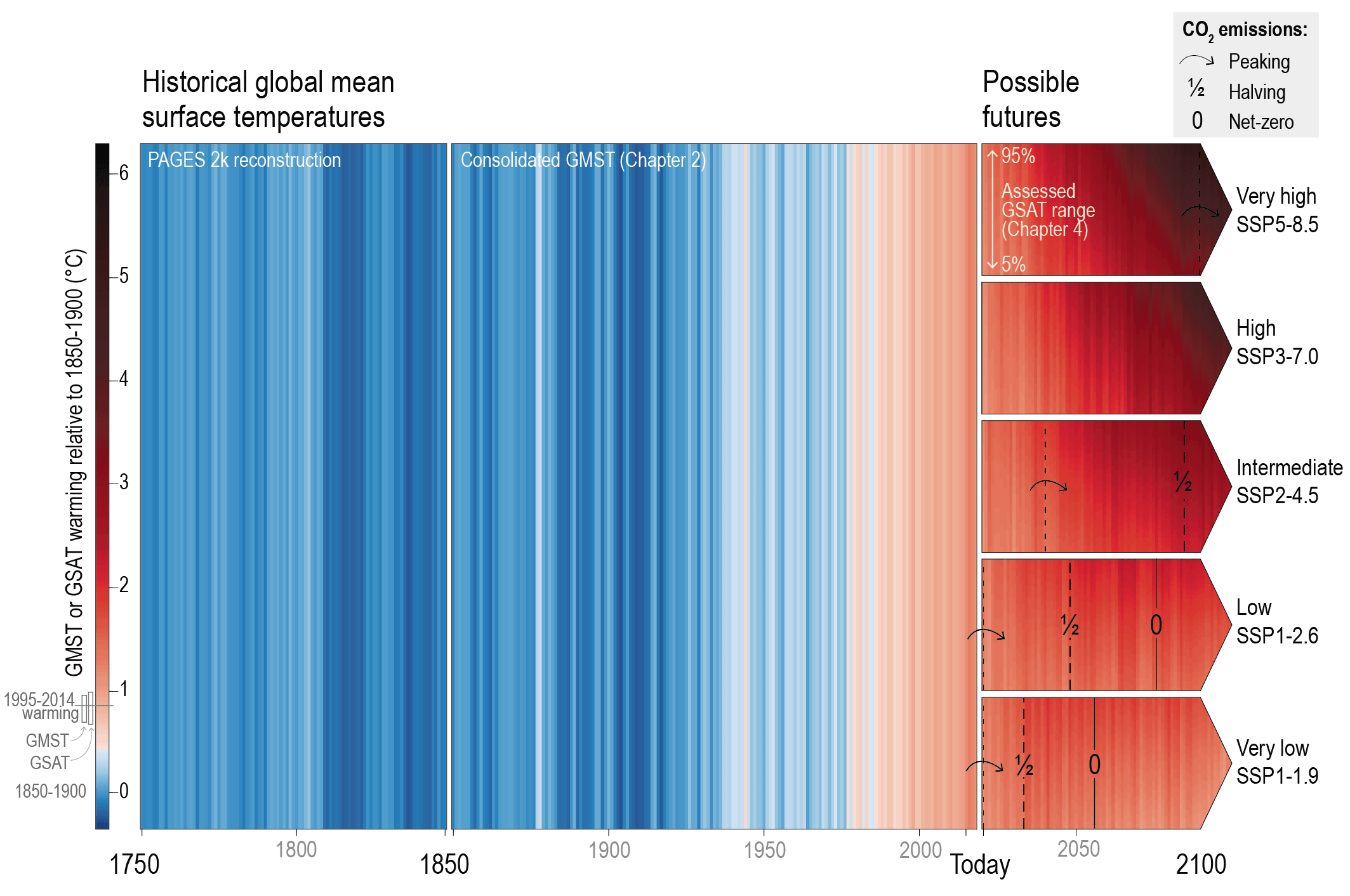

On Monday, the IPCC released its 2023 report on climate change, and it’s pretty grim. Scientists have given us a “final warning” on the climate crisis, warning that only swift and drastic action can avert us from irreversible catastrophic warning. The language is blunt, the warnings are dire. We need to act now, in many different areas, to avoid the dangerous temperature threshold.

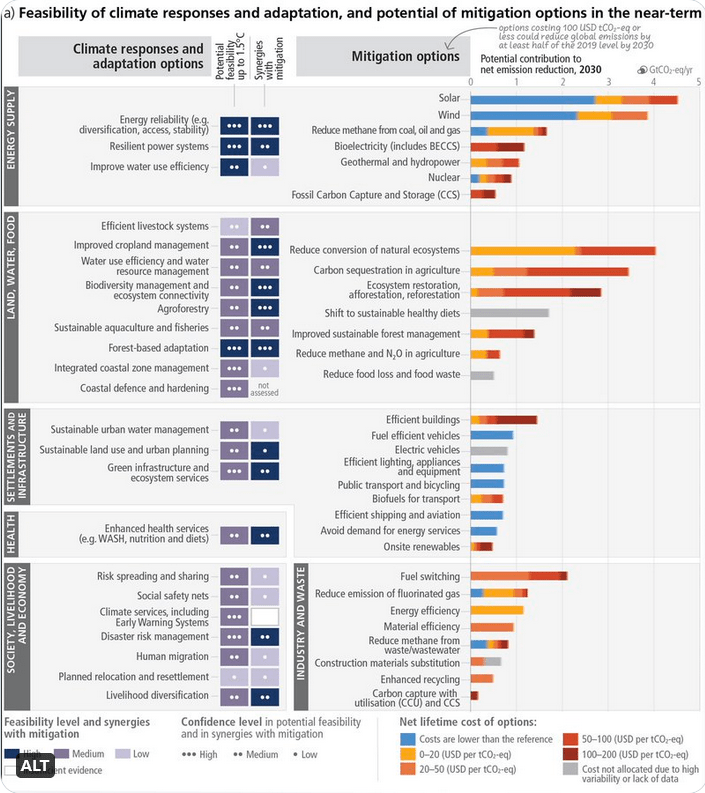

Part of the report offers potential solutions, many of which are available today and need to be implemented at scale around the globe. Here’s a chart showing potential ways to mitigate this crisis in the short term:

For example, climate scientists recommend that we adopt sustainable land use and urban planning (e.g. more infill and less suburban sprawl.) They also recommend more public transit and bicycling infrastructure. Reducing people’s time in cars is important, as is ensuring that buildings are energy-efficient.

We reached out to Jenny Schuetz, an urban economist at Brookings Metro and the author of Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing Systems for her thoughts on the report.

We reached out to Jenny Schuetz, an urban economist at Brookings Metro and the author of Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing Systems for her thoughts on the report.

We were particularly interested in how we can measure the climate impacts of growth in a place like Chapel Hill and Carrboro, where we see “climate conscious” voters and elected officials opposing zoning reform, bus rapid transit, and greenways.

Here’s what Dr. Schuetz said:

Schuetz: There are two big misconceptions that muddy the waters around the “true” climate impacts of urban growth.

First, too many people associate “I see trees and grass in my neighborhood” with “my city is climate friendly”—while not looking past their own neighborhood to land use patterns for the larger region.

Preserving low-density housing with yards in Chapel Hill (or Arlington VA, or Berkeley, or Austin) effectively pushes new housing & commercial development out to the exurban fringes, which in requires tearing down a *lot* of trees and converting open space (farmland, fields, forests).

Infill development also is more climate friendly because it makes use of existing streets, sidewalks, water and sewer infrastructure – all of which has to be built from scratch when we build suburban subdivisions. Long-time homeowners in Chapel Hill too often don’t see for themselves the exurban growth, the loss of trees and addition of highways in what used to be open space, so they can ignore the consequences of protecting their own backyards.

Second, much more broadly than urban growth, Americans have been misled into thinking that fighting climate change is an individual choice, about our own personal behavior (guilting people over recycling is a great example). But if you look at the list of adaptation & mitigation measures recommended by the IPCC, they require large scale systemic *collective* actions.

It’s not just about whether you walk to work and carry reusable grocery bags – if you care about reducing climate harms, you need to support *policies* that make it easier for *other people* to live low-carbon lifestyles. That means throwing your political support behind infill development, greater funding for public transit, showing up to community meetings to argue in favor of dedicated bus and bike lanes—and accepting that driving & parking in cities should be a lot more expensive.

For too long, we’ve bought into the idea that each person individually can choose to live a climate virtuous life, without having policies and market structures in place to guide everyone’s actions. That’s not going to get the job done, and it’s a distraction from the collective action we desperately need.