One of the arguments CHALT frequently makes against dense infill multi-family housing is that “the cost of serving residential development (money going out) exceeds the amount coming in.” They repeatedly cite a 2012 study commissioned by Chapel Hill’s former town manager– Here’s a recent example from NextDoor:

There’s just (several) problems with this. Let’s wade in, shall we?

First, the document CHALT continually cites is from 2012 and based on development patterns and data from 2009-2010. It’s 2022. Things have changed in Chapel Hill.

If you read the 2012 report, you’ll see that the author of the report acknowledges that it has limitations. The author writes, “It is important to recognize two important limitations of analyses such as the one presented here. First, [cost of community services] studies highlight the relative demands of various land uses on local fiscal resources given the current pattern of development. As such, one should be cautious in extrapolating from the results of studies such as this in order to gauge the impact of future patterns of development on local public finance.”

Again – just to make the point clear – the author tells us that it’s a point in time study and shouldn’t be used to gauge the impact of future patterns of development.

The 2012 report states that, at the time, Chapel Hill’s residential uses “contributed between 92¢ and 98¢ to the Town’s coffers for each dollar’s worth of services that it receive[d].”

The reason the author finds a range of between 92¢ and 98¢ is that he analyzes residential uses in two ways:

- In the first analysis, multifamily housing (apartment buildings) was counted as a commercial use rather than a residential use (e.g. single family homes, duplexes). This resulted in a lower residential sector contribution to the tax base of 92¢ for every dollar in services it received.

- In the second analysis, multifamily housing was treated as a residential use along with single-family homes and other lower-density housing types. This resulted in a higher residential sector contribution to the tax base of 98¢ for every dollar in services it received.

In other words, back in 2010, residential development was close to breaking even from a revenue standpoint – and multifamily housing helped rather than hindered the town’s fiscal health.

And that was before we saw several new, large apartment buildings come online. Apartment buildings, for the past few years, have been very, very good for Chapel Hill’s tax revenues.

Take, for instance, the Berkshire apartments near Whole Foods. They are assessed at $82 million, have near-zero children in public school and consume almost no county services and very little city services. And for the past four years, they’ve been the number two taxpayer in Chapel Hill.

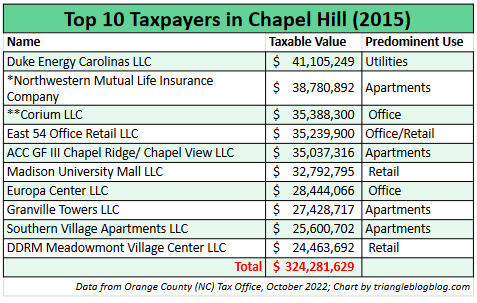

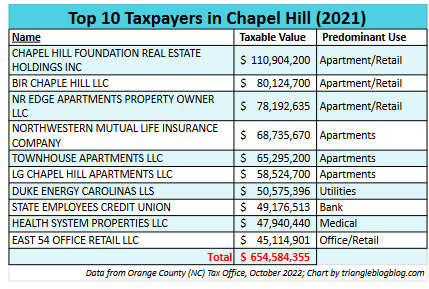

In fact, mixed-use apartment buildings dominate the top taxpayers in Chapel Hill and Orange County and have since 2015

CHALT may not like dense apartment buildings, but the six-story mixed use buildings tend to bring in far more in tax revenue than they generate in services (and often have few to no school-aged kids in them.) The top six taxpayers in Chapel Hill in 2021 (based on taxable value) were all apartment buildings. This is a remarkable shift from 2015, when Duke Energy topped the list of taxpayers and there were only 2 apartment buildings in the top six. We’ve pulled out the data, which is prepared by Orange County annually:

*Note the values in these tables are taxable values, which are used to determine the far lower amount of actual taxes paid.

What changed between 2015 and 2022?

In 2014, Chapel Hill implemented form-based code, which has helped upzone the 163-acre Blue Hill District along Fordham Boulevard. As a result, a bunch of apartment buildings now dot Fordham Boulevard.

Also, since the time the cost of community services analysis was conducted, we’ve seen the construction or redevelopment of large apartment buildings downtown or along MLK.

How much in property taxes have these apartment buildings paid?

There’s no quick way to determine the aggregate amount of property taxes paid by apartment buildings or single-family properties (reminder: we have day jobs). But some simple analysis of recent tax revenue data suggests that apartments are doing some heavy lifting in Chapel Hill.

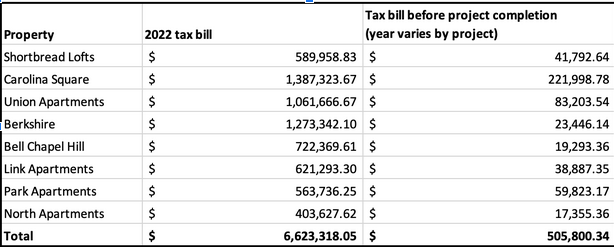

We looked up the most recent tax bill for eight apartment buildings that would not have been included in the 2012 cost of community services report. And wowzers, these guys are paying a lot in taxes!

Combined, these eight apartments will pay $6.6 million in property taxes in 2022. By our estimates, had these complexes not been built or redeveloped, the same parcels on which they are located would only be generating about a half million in property taxes per year. (For context, the Town of Chapel Hill anticipates roughly $35 million in property tax revenue this year. The $6 million in property taxes paid by the eight apartments, however, is shared by the town, the county, and the school system).

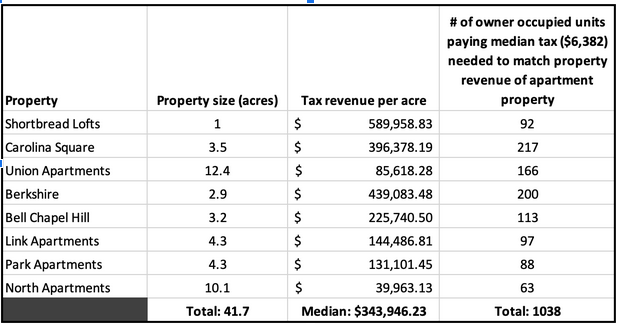

Not only do these eight apartments pay a lot in taxes overall, they also generate a large amount of tax revenue on a per-acre basis. In addition to building densely being a more efficient and environmentally-friendly use of land, it’s also tax efficient. As shown in the table below, the eight apartments generate median tax revenue payments of roughly $343,946 per acre.

Compare that to the median tax bill for owner-occupied homes in Chapel Hill, which was $6,382 from 2016-2020 (American Community Survey). If we assume a one-third acre lot generates that amount, then single-family homes should generate $19,146 per acre.

Some people in Chapel Hill wish none of these eight apartment buildings were ever built. But if we wanted similar levels of revenue from single-family homes that these buildings bring, we’d need to build over 1,000 single-family homes (which would require over 350 acres of land, assuming one-third acre lots, versus 42 acres taken up by the eight apartment buildings). That’s a lot of trees to cut down….

So, does residential development now pay for itself in Chapel Hill?

We cannot definitively say based on this simple analysis but it’s hard to think it doesn’t, especially because the 2012 study found that it nearly did then and since then the town has started building more densely. For a number of reasons, it makes sense that large, dense apartment complexes are a great financial deal for the town (and county and the school system):

- Many apartment residents in Chapel Hill are UNC students, which means many services they need (library, healthcare, recreation) are provided to them by the school, reducing their need to rely on town or county services (they also pay twice for Chapel Hill transit, once through student fees and once their rent payments that contribute to their landlord’s tax payment). Others are recent graduates who don’t have kids in the school system.

- Large apartments are more self-sufficient than single-family homes. Their trash, recycling, and yard waste is probably collected by private contractors instead of the town or county. Due to their modern construction and security features, they are unlikely to require more fire or police services than single-family homes.

- Most of the large apartment buildings are infill developments that take advantage of existing infrastructure, like water, sewer, and roads. When new infrastructure is needed on site, the developer pays for it, not taxpayers.

OK, so what do we do with this information?

It’s the holiday season and a new year is coming. Consider making a resolution to accept that these apartment buildings supply much-needed housing in our community and raise a lot of revenue for town. Revenue we need for things like pickleball courts and greenways and splash pads and fare-free transit and a beautiful library. And if there’s room on your mantle this year, maybe hang a stocking for our renter friends who are such a blessing to this town.

Notes

Data for the analysis of the eight apartments is from Orange County land and tax records. For six of the eight apartments, a one-to-one comparison could be made of tax revenue before and after construction on the subject parcel. For Carolina Square and Link Apartments, which are part of larger development projects, parcels have shifted over time and a direct comparison is not possible (for example, what is now the Link Apartments parcel used to be part of a Glen Lennox parcel). In these cases, we estimated the previous tax payment by estimating the acreage of the new apartment building sites, determing the ratio of those sites to acreage of the the larger developments, and applied that ratio to a pre-construction tax bill for the larger development. That is, if the Link Apartments parcel is 10 percent of the size of the Glen Lennox parcel it was carved out of, we estimated that the Link Apartments parcel used to contribute 10 percent of Glen Lennox’s total tax payment. In the case of Carolina Square, a similar estimation was made. Carolina Square includes office, retail, and Granville Towers. We have attempted to isolate the 2022 tax bill for just the Carolina Square apartments (excluding Granville), but could not determine if ground floor retail in those buildings is included in the buildings’ tax bills.

This piece was written by Stephen Whitlow and Melody Kramer, both of whom would like to thank Orange County for preparing the annual “Top 10 Taxpayers” spreadsheet.