Over the years, one of the most consistent defenses of burning coal at UNC-Chapel Hill’s cogeneration plant is that it’s a very efficient and clean operation.

Whenever I write about Cameron Avenue, the common response is that it’s a really clean coal plant.

I’ve been through the place, got the grand tour and a solid explanation of fluidized bed combustion and other things that reduce emissions. I’ve been through a lot of coal plants. My Dad helped design and build power systems including coal and natural gas plants.

So yes, in comparison to large-scale plants like, say, the old Dan River Steam Station (pictured above) or Belews Creek, Cameron Avenue emits a plume that’s less dirty per kwh.

This piece was originally printed in New Hope City, a Substack written by Kirk Ross. You can subscribe here.

But beyond air pollution, the cogeneration plant, like all plants with coal-fired boilers, produces coal ash.

Lots of it.

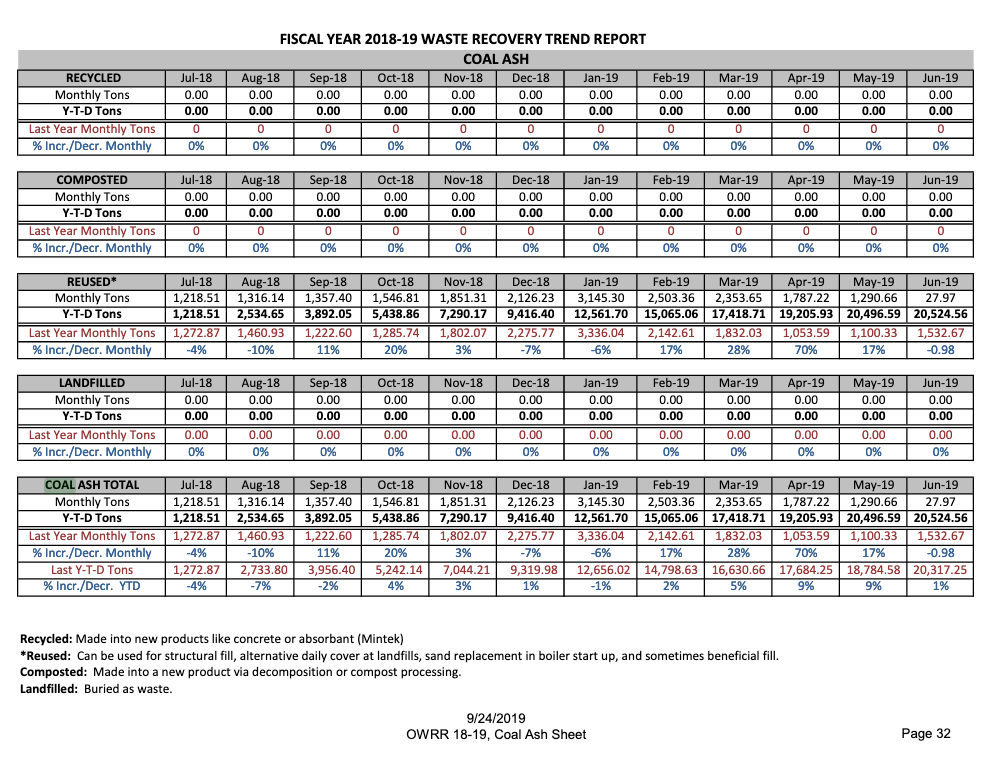

According to the university’s 2018-2019 recycling and waste reduction report, the Cameron Avenue cogeneration plant produces roughly 20,000 tons per year.

That’s one ton for every undergraduate student on campus per year or a little more than a 1,000 pounds a year for everyone on campus — undergrads, grad and professional, faculty and staff.

The spin on what happens to all that coal ash has always been that it goes into concrete products and other “beneficial uses,” a term of art in the state’s Coal Ash Management Act, passed in the wake of the 2014 Dan River coal ash spill. Beneficial uses in the bill include using ash in construction products or as structural fill for highways, airport runways and similar projects.

The university has been quick to point out that the coal ash leaves Chapel Hill and up until a few years ago would tout its coal ash recycling program.

An important and eye-opening investigation by Reuters of universities still heavily reliant on fossil fuels featured extensive reporting on UNC-Chapel Hill and tracked down what’s happening to Cameron Avenue coal ash today.

Reuters — U.S. colleges talk green but they have a dirty secret

Reuters — How Reuters analyzed emission rates for U.S. campus power plants

The story, throughout which the university declines to comment, contains this paragraph:

UNC pays trucks to haul its coal ash and other waste 60 miles north across the state line to South Boston, Virginia, a hamlet of 8,000 people. There it is dumped into an unlined pit, an average of 40 tons a day, according to the town manager. The rural community is about 60% Black and the median household income is $40,087, about half that of Chapel Hill, according to U.S. Census data.

Let’s go over a few things again w/bullet points. According to the Reuters report:

• 40 tons per day

• to an unlined landfill

• in a lower income, mostly Black community

• just across the Virginia border

• the university declined to comment

Please read the rest of the story.

As nasty as that looks, the Cameron Avenue coal ash arrangement cleans up pretty good on paper. Until last year, the university had a Coal Ash Page in the annual campus recycling report with a breakdown of what happens to the coal ash in four categories — recycled, composted, reused, and landfilled. The university’s coal ash is listed entirely under reused, which has an asterisk.

The key at the bottom of the chart reads: “*Reused: Can be used for structural fill, alternative daily cover at landfills, sand replacement in boiler start up, and sometimes beneficial fill.”

After sitting through lengthy legislative hearings in 2014 following the Dan River coal ash spill and following the bill, S729, I can assure you that this was exactly the kind of arrangement that raised concerns over proposed language that would allow coal ash in some cases to go to unlined landfills. The structural fill provisions in the final version of the law limit the size and scope and require extensive reporting of facilities that take coal ash in North Carolina.

The fact that Cameron Avenue’s coal ash crosses the border into a state with less strict rules deserves greater scrutiny. No doubt there is a very simple explanation.

As the current controversy over the coal ash previously deposited at a university dump off Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard reminds us, you don’t have to look far or go back too many years to be reminded of the university’s legacy of coal.

Add to it that an affordable housing project at the site of the former Chapel Hill police station is at a standstill while university produced coal residuals are tested and assessed.

The testing is critical because as Duke University’s renown researcher on coal ash and its toxicity Avner Vengosh will till tell you, all coal ash is not the same. There are regions that have higher content of toxic substances.

It’s unclear how much if any testing UNC-Chapel Hill regularly does on its coal ash and what the breakdown is for the stuff going into that landfill in Virginia. Part of the legacy of coal on campus is looking the other way or at best, rationalizing it away.

In doing research on this post I found an incredibly unsettling section in a recycling and waste reduction presentation from 2008. It gives you an insight into the kind of institutional thinking that’s swept coal ash under the rug. It reads:

Coal ash, which is a by-product of power and steam production at our cogeneration facility, is actually the largest waste stream on campus. Generating 36,557 tons of coal ash this year, it is three times the total campus waste stream–recycling and trash combined. With a waste stream of that magnitude, we do not include the coal ash statistics in the overall recycling and municipal solid waste totals. With that said, the coal ash is recycled!

There are a lot of questions still unanswered, but as more information of the true cost to our community and others of keeping the Cameron Avenue plant operating emerges, the balance between doing something and doing nothing shifts steadily toward change.