It took us a long time to write about the potential extension of the water and sewage service boundary in the southern part of Chapel Hill because we wanted to make sure we had a handle on the terminology.

That took a long time. We talked to a lot of people, including town staffers and former and current council members in both towns. We asked everyone to define the core terms in their own words. The Town of Chapel Hill made a really helpful glossary. We asked folks to point to parts of maps. There are so many maps.

This is a dense, confusing, and jargon-heavy topic. There are many terms. There are so many planning agreements.

And we apologize: we don’t normally lead off pieces with caveats and pages of definitions and historical context. But we can’t really talk about this messy, complex topic without the history and without understanding these terms.

So without further adieu, let’s chat about the Water and Sewer Management, Planning, and Boundary Agreement, which has the unfortunate acronym WASMPBA. That’s pronounced Wah-Sam-Bah.

Was-Sam-Bah

In the mid-70s, there were concerns that Chapel Hill and Carrboro would run out of water. Restrictions and conservation were put in place: no watering lawns, no washing cars, and snack bars at UNC were “barred from serving coffee, tea, or hot chocolate because of the water needed to make them.”

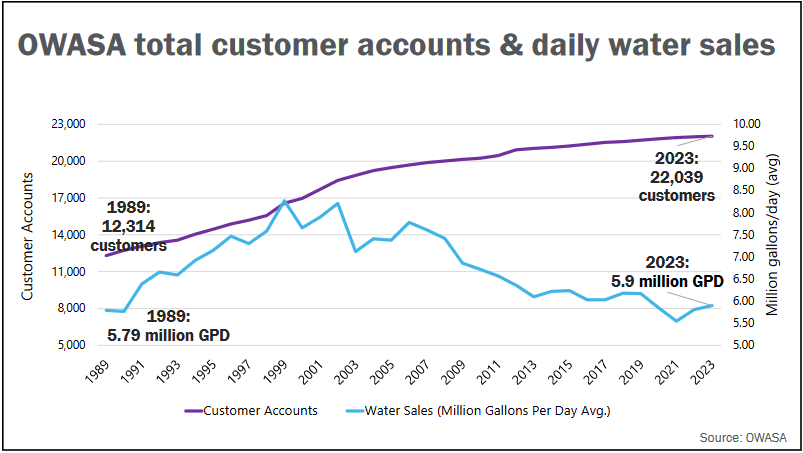

Fears returned in the early 2000s, when there was a record drought across North Carolina. In response, OWASA – the agency that supplies water to Chapel Hill and Carrboro – implemented several water conservation initiatives, including tiered block rates to incentivize people to use less water. They also worked with UNC to create what’s called a reclaimed water system. The reclaimed water system, which went online in 2009, uses filtered wastewater for things like cooling and flushing toilets across the UNC campus.

These initiatives did a bang-up job of reducing our community’s water usage. OWASA’s average day water sales in 2023 (which you can see below) are roughly at the level of what they were in the late 80s. Technology and economic incentives have kept the water usage low, even as the population of our region has grown. (In full disclosure, Mel serves on the OWASA board of directors but is not representing any view but her own in this piece.)

A shortened condensed history and definition of terms

Let’s return back to the late 80s and early 90s. At the time, all of the local governments in Orange County and OWASA were worried about sprawl and water. They put together a working group in 1994. Seven years later, they came up with an agreement that basically says “All five entities – Orange County, OWASA, and the Towns of Chapel Hill, Carrboro, and Hillsborough – will have to agree to extend water and sewage service beyond the boundaries of its current primary service area.” They also agreed to link the agreement to land use planning as “part of an overall strategy to align local government land use decisions with public water and sewer permitted areas.”

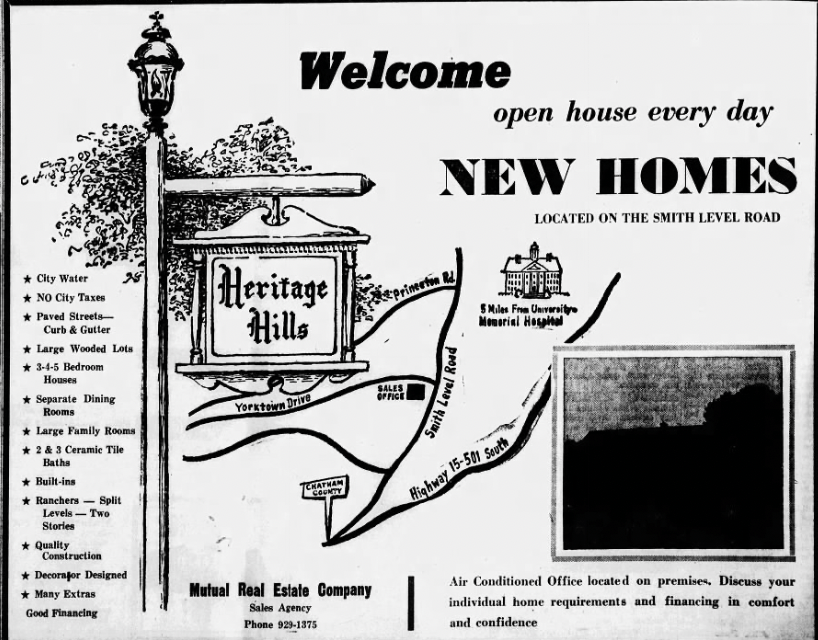

But here’s where things get tricky. Carrboro said they wouldn’t sign the agreement unless Rangewood and Heritage Hills were included. Both of those neighborhoods were outside the “primary service area” but already receiving water and sewage from OWASA. Chapel Hill said they wanted the agreement to be amended so that it encompassed their urban services area.

And so on.

Over the years, amendments have been made to extend the area in certain places. There’s a detailed document outlining all of these changes that goes into much more depth than what we’ve presented here, if you’re really into local water and sewage history. (And if you are, there are currently openings on the OWASA board and we encourage you to apply!)

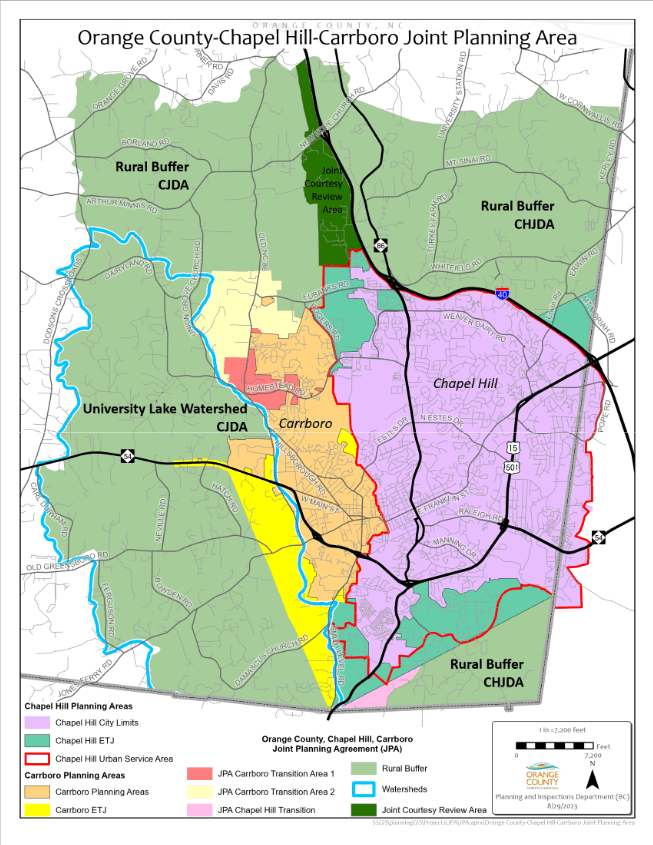

But to recap: All five governments have to agree to change boundaries. They sometimes have changed the boundaries. And there are a bunch of terms that relate to this agreement. We’ve summarized them in this table:

| Area | Definition | Who has planning authority? |

| Urban Services Area / Primary Services Area | the area where water and/or sewer service is now provided or might reasonably be provided in the future. | Town of Chapel Hill and Town of Carrboro |

| Extraterritorial Jurisdiction (ETJ) | Outside of towns’ corporate boundaries but adjacent to town | Town of Chapel Hill and Town of Carrboro |

| Rural buffer | Sits outside of Chapel Hill and Carrboro and covers approximately 37,250 acres (or 58 sq. miles) of land zoned for agriculture, forestry, and low-density development that will not require future water or sewer line extensions. | Orange County |

| Transition areas | Areas that Chapel Hill and Carrboro plan for in the future, but are not part of the current municipal city boundaries. | Towns’ land use regulations apply; county has final approval on rezonings |

And here’s a map showing where they are

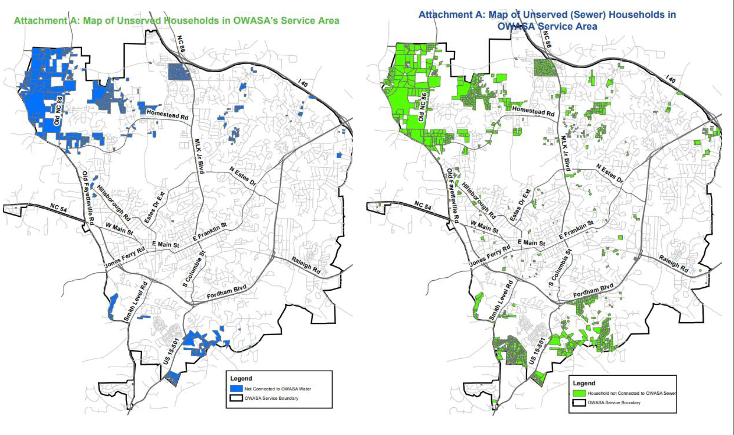

OWASA supplies water and sewage to everyone living in the primary service area limits, with the exception of 550 households that are not currently connected to water service and about 1,200 households that are not currently connected to sewer service. You can see them on the map below.

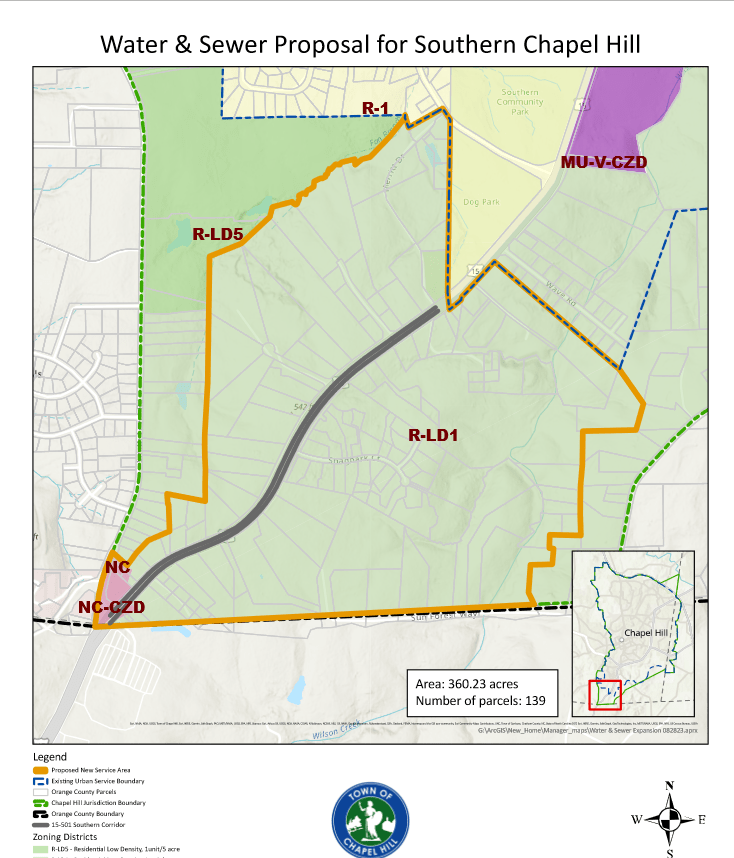

Which brings us – finally! – to the present day. There’s a little area just outside of the “primary service area” that sits within Orange County but outside of the Chapel Hill town limits. It’s just south of Southern Village’s dog park. It’s about 360 acres. (That’s about the size of Southern Village – which is 312 acres.)

And it doesn’t have water or sewage service. It’s the part that’s bordered in orange, below.

Last June, Aaron Nelson from the Chamber petitioned the Chapel Hill Town Council to expand the service boundary for water and sewage to include this area, which is in orange above. Notably, it would not actually extend any OWASA water or sewage service. It just gives us the ability to do so when planning for the long-term future. (In other words, this is something that could happen in 30-50 years, not immediately.)

This is an area that will be developed in the future. It sits on the 15-501 corridor, right by the forthcoming bus rapid transit system. It contains a large plot of town-owned land, which the town of Chapel Hill has said it would like to develop affordable housing on. (It’s much cheaper to build permanent affordable housing on land that the town owns.) And it’s perfectly situated for missing middle housing: the duplexes, triplexes, and quads that sell for less than single-detached homes.

The question becomes: Does this area remain on septic and well water, or do we allow future development just south of the Southern Village dog park to hook into OWASA?

What’s wrong with leapfrog development?

When Orange County and its municipalities first embarked upon planning for growth in the 1970s, there was consensus that they wanted to avoid “leapfrog development.” As the name implies, leapfrog development occurs when a developer “leaps” over nearby, but expensive or protected undeveloped land, to build a neighborhood that is disconnected from urban services, like water and sewer.

While the homes in the leapfrog neighborhoods tend to be less expensive to purchase than those ten or fifteen minutes closer, over time they cost more in services for local government, including fire, police, and education, because they’re far from existing schools and police and fire stations. Compact urban development, or infill housing, can be more expensive at the outset, but has lower costs over time. When Orange County began planning its future growth, they wanted to avoid future leapfrog neighborhoods like Heritage Hills.

Almost fifty years later, we are again seeing “leapfrog” development, only this time it is in Chatham County, which is not under the planning authority of Orange County. The Briar Chapel neighborhood had to build its own sewage treatment plant, which has had lots of problems, and Pittsboro is in the process of connecting its water and sewer infrastructure to Sanford after suffering water quality issues, all the consequences of poor planning by our neighbors to the south.

But our visionary planning from the 1970s gives us options that we would not have had if we had allowed all of southern Orange County to turn into suburban sprawl. Planners fortuitously reserved land alongside 15-501, a major highway, for future growth, to be revisited when we had exhausted other options.

Now, in 2024, we know four things.

First, we know that septic systems have a lifespan – and that many of the septic systems in this area will reach the end of their life span in the next 20-30 years. Failing septic systems can contaminate well water and nearby bodies of water and the effects of climate change will exacerbate that situation. Upgrade and maintenance costs fall on the homeowner, and can be prohibitive. (Furthermore, there are some existing OWASA water and sewage lines within the area proposed as these lines were in place prior to 2001. The change in service area would allow those existing residential properties to choose to extend water/sewage service to their existing residential units – which is similar in price as redoing an entire septic system.)

Second, we know that we are living in one of the fastest growing regions in the country, and that Chapel Hill is not building enough housing to keep up with demand. That’s why prices are rising—dramatically—and why developers are building thousands of homes in Pittsboro despite the fact that almost everyone who lives there will have a 30-minute commute, or worse, just to get to work.

Third, we know that, left alone, all of the lots that are currently in the area being considered for water and sewer service will become $2 million+ custom-built McMansions. This is already happening – one only has to look at the existing development in this area to see that plots purchased are not remaining naturally occurring affordable housing but are being torn down for single, very large estates.

We already have a lot of housing like this in the rural buffer, and we don’t think we need more of it.

Fourth, we know that adding the possibility of water and sewer service to these lots will enable higher density development. (And the cost of adding water and sewage to denser development is less than for sprawling single-detached homes – there are fewer pipes to lay and maintain.)

Even more importantly, the existence of developments, including apartment buildings, up and down 15-501 as soon as you cross over the Chatham County line suggests that we can get dense housing here if we want it. Instead of large single family homes, we can approve cottage courts, quadplexes, and smaller homes on small lots. We can add greenway connections as we grow, allowing people living in Southern Village to get to the Chatham County Wal-Mart in a 10- or 15-minute bike ride, or people living in these new homes to get to work at UNC by taking a short bike ride coupled with a bus-rapid trip rather than having to pay to park on campus. (It becomes much easier to build sidewalks and greenways after development comes.)

Who is opposed?

A group calling itself the Southern Entryway Alliance is opposed to expanding the service boundary for water and sewage to include this area. They have written many emails to the county commissioners, and spoken at public and business meetings. We mapped out the addresses they sent in a petition to the Orange County Commissioners on February 20 and then entered each address into OWASA’s public service area map.

Notably, almost none of the 65 signers live in the parcel under discussion – we counted 2 or possibly 3, at most. The vast majority of signers live in areas that were previously grandfathered in to OWASA’s water and sewage agreement. (Of the 48 unique households that signed, more than 70% already have access to OWASA water and sewage, several live no where near the southern part of Chapel Hill, and two live outside the county.) This underscores that the opposition to expanding the service boundary mostly consists of households that were themselves grandfathered in.

Septic Shock

There’s a great and detailed piece by Nathan Cummings in the Yale Law and Policy Review that details how local communities “frequently resist sewer expansions in order to keep development down and new residents out.” It’s well worth a read in full, as it details how local politics shape where wastewater boundaries start and end – and how those exclusionary policies have played out in high-demand areas like our own.

Extending water and sewage beyond Southern Village isn’t going to happen in the next 5-10 years. It’s a forward-thinking way to think about what the southern part of Chapel Hill should look like 30-50 years from now: Should it contain sprawling multi-million dollar single family homes, without the density to support amenities – or should we envision a future with more deliberate developments like Southern Village, in which many types of housing are available and amenities are within walking distance of residents, and residents are able to bike, walk, and rapid-transit to work and play? As Chapel Hill changes and grows, whose voices are we centering in those discussions, and how will they shape the next 30-50 years?

This piece was written by Melody Kramer and Martin Johnson.