The Town of Carrboro, known for its grocery co-op, arts festivals, and farmer’s market, and led by a council that just last year passed a resolution describing the town as a “peace-loving community” opposed to “tyranny, unprovoked aggression, and war,” today feels like an extremely unlikely home for a defense contractor to set up shop. Yet for a few years in the 1940s, Carrboro was a key contributor to the military effort, hosting a munitions plant that would produce over a hundred million anti-aircraft shells used by the U.S. Navy during World War II.

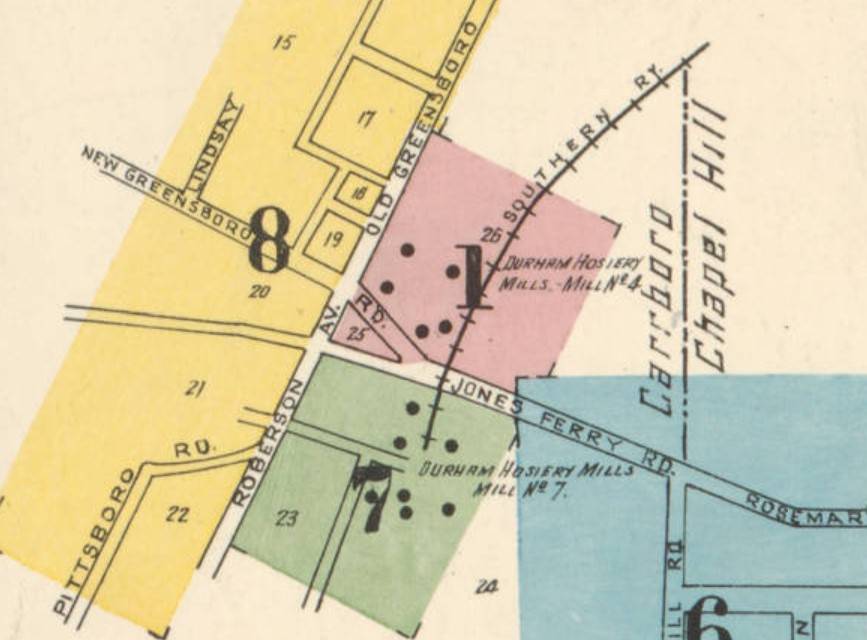

In February 1942, local newspapers first published reports of a war munitions plant coming to Carrboro. It was welcome news for a community still struggling to recover from the closure of the Carrboro textile mills in the 1930s. The factory would be operated by the National Munitions Company, which contracted with the U.S. government to produce anti-aircraft shells for the Navy. They would take over the building on Roberson Street formerly known as Durham Hosiery Mill No. 7.

When the factory opened in June 1942 it initially employed 125 people and, as more shifts were added, eventually had more than 500 people employees. The News of Orange County described the influx of workers from surrounding communities: “The greatest part of the Munitions workers came from Orange County. Men came from their farms, women left off their housekeeping, filling station operators, store clerks, mill workers – all kinds of people from all kinds of jobs came to Carrboro.”

The work involved mixing explosives and loading and packing shells. Ben Williams, who worked at the plant, recalled the work in an oral history recorded with the Chapel Hill Historical Society. He described it as an “assembly plant,” working with shells and raw materials that came in by train. “We put all the explosives – it was a loaded shell when it left out of there. Anti-aircraft, twenty millimeters anti-aircraft. Made something over one hundred and eight million of them over there.”

While most of the employees worked at the former mill building, some of the work took place elsewhere in town. Columbus Oakley recalled working in a building known as “The Bottom,” located “down in a valley” behind the main factory. It’s not clear from Oakley’s oral history how far away the building was, but it sounds like it may have been roughly in the area where the South Green shopping center is located now. The employees at The Bottom worked with explosive powder brought in from a farm near Chatham County line where it was stored. They pressed the powder into pellets which were taken up the hill to the factory where the shells were assembled and packed.

Who worked at the munitions plant

The munitions plant employed a relatively diverse workforce. The majority of the employees were women, which was not unusual in World War II-era factories. The plant also employed Black workers, though gender and race were factors in job assignments. Columbus Oakley recalled that Black men and white men worked together at The Bottom, while Ernest Hearn remembered that the majority of the Black men employed at the factory worked in the loading areas. All or most of the women at the factory worked in the main building.

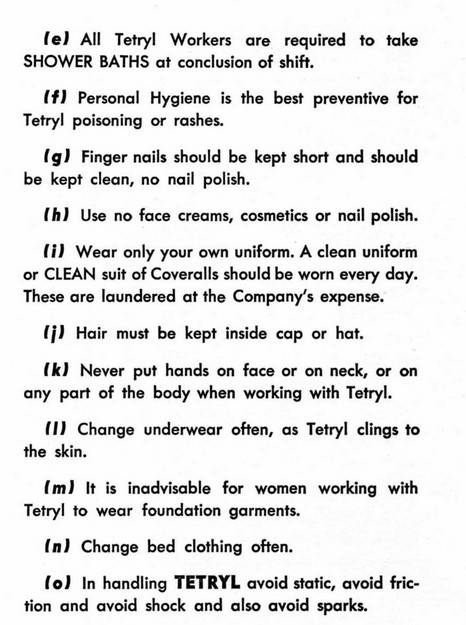

There were significant health hazards to the work, not entirely unlike those experienced by former mill workers. One local historian writes: “those that had once been covered with lint now went home with yellow dust on their arms and faces.” The yellow dust was tetryl, an explosive powder used in the shells. Former employees Ernest Hearn and Columbus Oakley talked about the tetryl powder in their oral histories. Hearn recalled the stains it left on his skin: “If you use it, it’s just like picking blackberries . . . Get it on your hands and all you can do is let it wear off.” Oakley was more explicit about the health concerns: “I didn’t like it. There wasn’t much work to it, no labor to it, but it wasn’t very healthy . . . inhaling dust, tetryl dust . . . it affected your lungs. You had a cough . . . And it yellowed you up. Our hair turned red around the edges of our caps.”

The tetryl powder was also highly explosive. Columbus Oakley recalled “several small explosions” in which some of the employees “got burnt.” But there was at least one incident that was far more serious. Early in the morning of September 6, 1942, a large explosion shook Carrboro and Chapel Hill. The blast was big enough that a resident of Oak Street remembered feeling the effects: “every dish and everything in the house rattled.” Several employees were injured and one man was killed. It was the only reported fatality at the plant.

The potential health risks from handling tetryl powder are evident when looking at the munitions plant employee handbook, which included a lengthy section of “Special Instructions Applicable to Tetryl Workers.” Tetryl workers were required to wear clean uniforms every day, shower at the end of every shift, and “change underwear often, as Tetryl clings to the skin.” They were also required to drink at least a pint of milk every day and take vitamins provided by the plant physician.

In spite of the risks, the workers at the Carrboro plant were apparently doing an excellent job. In 1943, the plant workers were awarded the Army and Navy’s “E” for excellence, the highest honor given to civilian war workers. The plant was presented its “E” banner in a ceremony at Memorial Hall at UNC featuring government and university officials and the Navy Pre-Flight School’s legendary all-Black B-1 band. The band played patriotic songs and the recent hit “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” made popular by Chapel Hill bandleader Kay Kyser.

The munitions plant employees also proved to be reliable contributors to the war effort. When local businesses ran competitions to see whose employees would purchase the greatest number of war bonds, the Carrboro munitions plant regularly came out on top. (It could be that the munitions plant employees were more patriotic than their neighbors, but they also would have been well aware that their jobs were secure only as long as the Navy kept ordering shells.)

Bazooka Day demonstrations

It was a local war bond drive that led to one strangest events during this period: Bazooka Day. The Orange County 4th War Loan Committee designated January 24, 1944 as Bazooka Day in Chapel Hill and Carrboro. The day included rallies at local businesses and schools and a demonstration of military equipment brought in by soldiers from Camp Butner. The highlight was the demonstration of a bazooka, the portable rocket-launcher that was designed to defend against enemy tanks. The bazooka demonstrations were held at the munitions plant in Carrboro and in front of the Campus Y on the UNC campus.

The work at the plant was always dependent on the continuation of the war, but the end still came abruptly for its nearly 500 employees. Just a couple of days after the end of the war was announced, the National Munitions Company canceled its contract with the Carrboro plant, effective immediately. A few workers stayed on to help dismantle and pack the equipment, but the majority were faced with unemployment.

The building did not stay empty for long. As the post-war economy grew, the textile industry returned to Carrboro. The mill buildings were purchased by Pacific Mills in 1946 and operated as Carrboro Woollen Mills into the 1970s. After the mills closed, the Roberson Street building was demolished and replaced by a new community health center, which remained until the mid 1990s. This is the same building that was recently renovated and is now the new home of the ArtsCenter.

Sources:

Newspapers

Daily Tar Heel. 13 February 1942, 23 June 1942, 17 May 1946.

Chapel Hill Weekly, 19 June 1942, 11 September 1942.

News of Orange County. 23 August 1945.

Oral Histories

Ernest Hearn, 16 June 1975. Interviewed by Hugh P. Brinton. Chapel Hill Historical Society collection, Chapel Hill Public Library.

Columbus Oakley, 22 January 1975. Interviewed by Hugh P. Brinton. Chapel Hill Historical Society collection, Chapel Hill Public Library.

Ben Williams, 1 July 1974. From Chapel Hill Historical Society’s Generations of Carrboro Mill Families Oral Histories, 1974-1978 (collection 04205). Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

Publications

Frances L. Shetley and Lou Bonds, “A Place to Live: Carrboro, North Carolina.” 1978. North Carolina Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

[Documents relating to the performance of National Munitions Corporation Plant No. 5, Carrboro, N.C.]. North Carolina Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

Official presentation, the Army-Navy E to the men and women of the National Munitions Corporation of Carrboro, North Carolina for excellence in the production of war materials. North Carolina Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

“Instructions for the Guidance of Employees, National Munitions Corporation, Carrboro, N.C.” National Munitions Corporation, ca. 1942. https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/247989