With few exceptions, most people running for Chapel Hill Town Council—a part-time job that pays a tad over twenty thousand a year and requires you to work nights and weekends—are doing so for a reason.

Erik Valera is running because he wants to represent communities that are seldom heard in council meetings. Melissa McCullough is running because she wants to bring her expertise on climate change and the environment to bear in town government. Theodore Nollert is running because he wants to be a voice for students, renters, and young professionals who like to stay in this town, but fear they can’t because of the escalating price of housing.

And then there’s Elizabeth Sharp, who is running because she is concerned that a developer will build a duplex in her neighborhood and rent it out to students.

Make your 2023 municipal election voting plan

Beginning with the 2023 municipal elections, North Carolina voters will be required to show photo ID when they check in to vote. Voters who vote by mail will be asked to include a photocopy of an acceptable ID when returning their ballot by mail.

Check your voter registration now. You can look it up here. This is really important particularly if you’ve moved in the past year.

Make a plan to vote during early voting. This ensures that if there’s a problem, you can sort it out. Early voting runs from October 19-November 4. Here is the complete schedule of voting sites, dates, and times for Orange County.

Read about the new voter ID requirements. Every vote counts in North Carolina, and this information must be shared early and often. If you know of people who have just moved here, or students, or new neighbors, please let them know about registering and the voter ID requirements.

Before running for council, Sharp was uninvolved in local government

Until she filed to run for council in July, Sharp was not involved in local government. To my knowledge, she has never spoken at a council meeting, never sent an email to the town council inbox, and has never served on a town advisory board. She didn’t even vote in the last two town elections (2019 and 2021).

So why is Sharp running? From all available evidence, it appears that she only became interested in town affairs when she learned that the town council was considering a text amendment that would make it theoretically possible to build more diverse housing types in her neighborhood.

On February 27, the Town of Chapel Hill’s planning staff met with residents of the Glendale neighborhood, a small neighborhood off of Franklin Street where houses sell for $700,000 and up. In the meeting, which was recorded by the town, Sharp weighed in about why she was opposed to the changes, first complaining about traffic and students before veering into a broader critique of everything that’s been built in Chapel Hill since she moved here seven years ago. (Sharp is far from the first person who moves here only to complain that new arrivals are “ruining” Chapel Hill.)

Sharp believes all students are alike

While Sharp was presumably speaking off the cuff in February, in her campaign she has continued to emphasize her stance against adding more housing choices in neighborhoods. In July, shortly after she filed for office, she posted a blog post titled “What do you think about single-family zoning?,” in which she acknowledges some of the reasons that restricting neighborhoods to single-family homes is a bad idea (it leads to sprawl and inefficient use of infrastructure), but goes on to argue:

Unfortunately these same experts routinely leave unaddressed the fact that in America in 2023, real estate is one of, if not the most, complex and competitive commodities in our economy, particularly in a college town. In theory, we should be able to densify gently without disrupting the equilibrium of our community, and possibly even strengthen it. But in practice, the strongest force in American real estate is the primacy of return on investment. All other influences and outcomes are secondary at best.

…

One of the very special things about the parts of Chapel Hill near the university is the proximity of student neighborhoods to family neighborhoods. This is a boon to both the families and the students, who benefit from each other’s respective stability and energy. But if encroaching student rentals start to push families out of current family-oriented pockets – which have likely persisted near campus precisely because of single-family zoning, its other drawbacks notwithstanding – we will lose this special, delicate balance. Families will increasingly live on the edges of Chapel Hill, while students will inhabit the interior neighborhoods, close to downtown and campus. This will not only segregate the two populations, but drive non-student business out of downtown, where goods and services are accessible not only by car, but on foot, bike, or bus.

College students, as has been pointed out, are not monsters. They will not ravage neighborhoods out of malicious intent. They are just young, as we all were once, and they do the things young people do when living away from their families for the first time, in residences to which they have little financial or emotional attachment. Their landlords assume this and therefore invest minimally in maintaining properties that they cannot expect their tenants to treat carefully (again, return on investment carries the day).

In Sharp’s view, there are two types of residents—”students” and “families”—and Chapel Hill’s unique charm is that the student neighborhoods are segregated from the family neighborhoods. But if we add just a few more duplexes, it will lead to more students moving into neighborhoods that border …. a very large university campus. (Note: Sharp does not mention the long history of de facto and de jure racism inherent in single-family-only zoning, nor Chapel Hill’s role in promoting racial segregation).

It is also telling that Sharp has difficulty imagining any other populations that might currently live, or would like to live in Chapel Hill. In her view, now that duplexes are permitted in most neighborhoods, every property sale “pits the wallets of wealthy single-family homebuilders against the wallets of wealthy real estate investors,” with the latter presumably only interested in building homes for students who are living away from home for the first time, and will “have little financial or emotional attachment” to their homes. She writes:

Nowhere in this market-based solution are the needs of middle or low income residents represented, nor are the needs of young professionals looking to buy their first house, retirees wanting to downsize, or any of the other myriad family arrangements that “missing middle housing” is meant to serve.

Because Sharp appears to only be imagining 20-year-olds throwing wild parties and driving too fast, she misses the diversity of current and future residents who might be interested in living near campus. In her piece she links to a 2019 HUD study that notes that forty percent of renters are students, which means that the majority of renters (sixty percent) are not. While she might not want to live in a duplex near campus, there are certainly some young professionals, retirees, and others who would be happy to do so.

And of those students, many are graduate students, who have much more in common with young professionals than undergrads. Many medical students work early morning and late night shifts at the hospital, and are willing to pay exorbitant rents for homes near campus. They will benefit from having more housing choices. Likewise, many graduate students are also parents and need to live close to campus to balance their teaching and research responsibilities with taking care of young children. There are also many international students who cannot drive, and seek out housing near campus.

A duplex is a place where someone can live

On top of this, a housing type—a duplex, a backyard cottage, a garage apartment—is just that, a place where someone can live. In my neighborhood, which is near campus, there are a lot of homes, from mid-rise apartment buildings to townhomes, that were built before the zoning rules were changed in the 1980s. Some of these homes are for sale, others are rentals. Some are occupied by students, others by medical residents, still others by UNC staff. There is nothing about a housing type that determines its occupant, much as Sharp would like to pretend otherwise.

In this same post, Sharp proposes her solution to the difficulty low and middle-income people have with finding housing in our community, working with the affordable housing non-profits that already work closely with the town:

We are lucky to have well-established non-profit organizations like EmPOWERment, the Community Home Trust, and Habitat for Humanity in Chapel Hill. We should implement policy to streamline these organization’s access to properties in existing single-family neighborhoods. They need to be at the bidding table with the real estate investors and the wealthy homebuilders.

In this post, Sharp, who elsewhere states that the market drives everything, doesn’t acknowledge the essential problem with this proposal. Property owners, whether they’re single-family home owners or developers, want to sell their homes for the highest possible value, and it would not make sense for EMPOWERment, which focuses on very low income residents, or Community Home Trust, which purchases properties to resell at a lower cost to moderate income residents, to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to buy homes in expensive neighborhoods when their scarce resources could go further elsewhere. If Sharp had taken the time to talk to these organizations, she would have known this.

Sharp’s proposals to build affordable housing are not viable

In her answer to the Orange County Affordable Housing Coalition’s questionnaire, Sharp suggested that housing non-profits be given “higher-density zoning guidelines in existing neighborhoods,” but with the difficult economics of building affordable housing, the zoning would have to be exceptionally generous. (Disclosure—I am a member of the Coalition, but the Coalition does not endorse in municipal elections).

Does Sharp really think her neighbors who are opposed to duplexes would welcome a six-story apartment building in their neighborhood if most or all of the units are affordable? If so, terrific, but I don’t think it was the lack of affordability that was driving neighborhood opposition to housing choices. (We even have a case in point locally, where a developer is proposing to construct a 12-story apartment building adjacent to, but not in, the historic district with twenty-five percent of the units reserved for moderate-income people. As you might expect, the neighbors are opposed.)

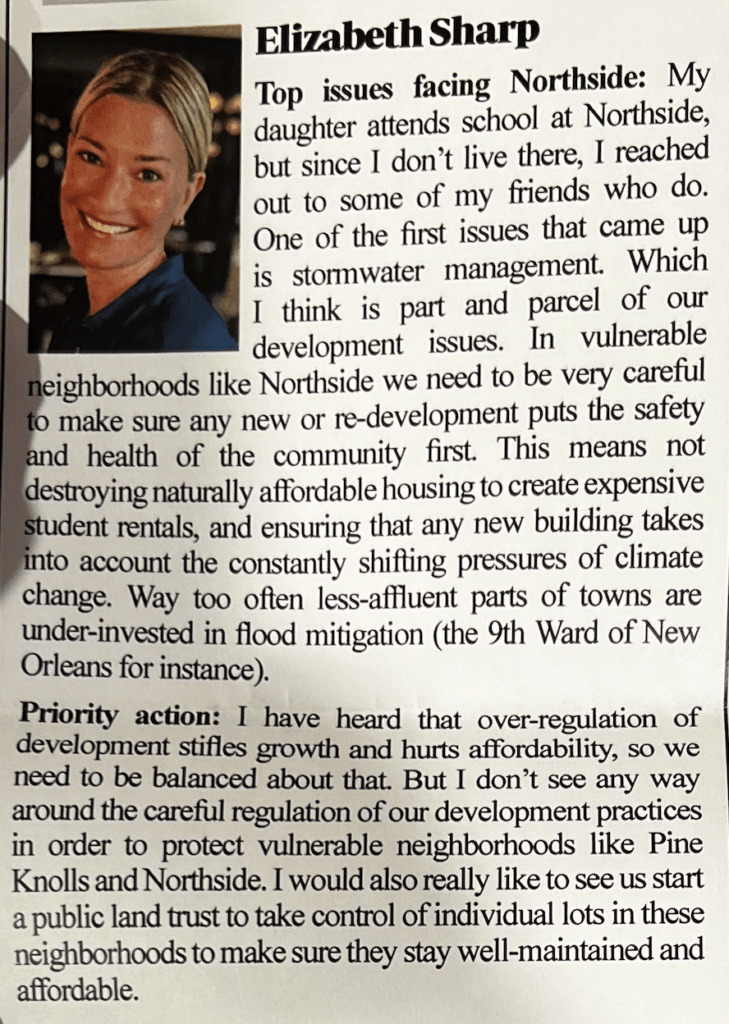

When interviewed for the Northside News, a print (!) publication that is distributed to residents of one of Chapel Hill’s historically black neighborhoods, Sharp suggests that they consider forming a land trust, seemingly unaware that Community Home Trust, a land trust that has a dozen homes in Northside, has been in the community for decades. Again, while it is understandable that Sharp, who only became involved in civic affairs eight months ago, would be unaware about the many strategies the town uses to preserve and build affordable housing, there’s a reason we value experienced and knowledgeable council members.

Does Sharp Respect the Town Council and Staff?

Over the past few months, it seems that Sharp is beginning to learn more about affordable housing and zoning, and her education continues on the campaign trail. In early September, she attended the Council Committee on Economic Sustainability (CCES) to hear a presentation by Mitchell Silver, the former planning director of the City of Raleigh and widely regarded as one of the most influential planners of our time. CCES meetings, like the council’s workshop meetings, are more informal affairs, designed for council members to engage directly with one another, and no public comment is permitted. Immediately after Silver concluded his remarks, Sharp, apparently unaware of this rule, raised her hand and began to ask a question before Mayor Pam Hemminger reminded Sharp of council rules.

This is an understandable misstep, and most people would recognize this and remain silent—and mortified—for the remainder of the session. But not Sharp. Just under a half hour later, Sharp again interrupts, saying she is aware that it is inappropriate for her to ask a question but wants to clarify something Silver said.

As someone who follows the council closely, I have watched many of these CCES meetings, and have attended a few in person. I cannot recall someone interrupting the meeting even once, let alone twice. I think these actions suggest something about the lack of respect Sharp has for the council, town staff, and the speakers they invite.

We need thoughtful town council members

As Sharp’s early campaign signs remind us, she is interested in “creating thoughtful progress,” three words that almost any candidate running for local office could use. In her campaign messaging she implies that the current council has not been thoughtful, as if council members do not spend hours every week thinking deeply about the town and how future developments will impact our community. She criticizes the council for not exploring “creative” solutions to our housing challenges, but then proposes policy solutions that reveal her ignorance. Recently Sharp gave an interview to WCHL in which she again articulated her key message on housing:

I think we need to remove our affordable housing solutions from the free market, largely because if we try to rely on market forces to fix this problem will always be adversely affecting the affordability of housing anytime we do anything that improves our economy or the quality of life at Chapel Hill. If we make it pleasant and financially viable to be here, demand will be high. And there is an upper limit to how much we can build before making it unpleasant to live here, at which point it becomes affordable just because no one wants to be here.

For Sharp, a Chapel Hill with more duplexes is a diminished place, with such poor quality of life that no one will want to live here. But for many others, who want to live here because they are in school, working at UNC or UNC Hospitals, or just trying to find somewhere to live as they age, a Chapel Hill with more housing would be a relief.