People in town who are generally opposed to any changes in Chapel Hill, such as the leadership of Chapel Hill Alliance for a Livable Town (CHALT) and like-minded town residents, have recently shared two comments about the nature of our changing and fast-growing region that are difficult to square.

First, we saw comments about the recent report on Wake County’s shrinking tree canopy. In 2020, Wake County had 297,242 acres of tree canopy, about 54 percent of the county’s land cover, but that represents a loss of more than 11,000 acres since 2010, or a reduction of more than 3.5% over that ten-year period.

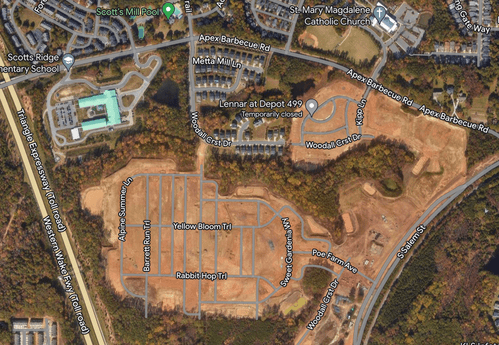

This should not particularly surprise anyone who follows development patterns in Wake County. New single-family subdivisions have been sprawling in rapidly growing small towns such as Zebulon and Wendell, and beyond into Clayton and Johnston County. Citizens have used this report to comment on the loss of trees in Chapel Hill through developments such as Aura, on the corner of Estes Drive and MLK Jr. Blvd., as well as the felling of trees linked to the construction of much-needed bicycle and pedestrian paths alongside Estes Drive, in front of an elementary school and a middle school.

Second, we’re beginning to see comments trickle into Council about a proposal for a 12-story, 157-feet tall condo building on Rosemary Street (we wrote about this last week). The building, on a lot that measures one-third of an acre, is proposed to include 56 for-sale apartments, 14 of which will be dedicated as for-sale affordable units, priced to be attainable by teachers, police officers, and UNC employees, with a 99-year affordability requirement. (The developer has said that the height makes it possible to provide such a high percentage of affordable units.)

CHALT has complained on social media that “This plan would create a very large building on the edge of the historic district, a building that would be completely out of scale with its surroundings.” The planned condos would sit across from a currently-under-construction lab building, also on Rosemary, which is almost exactly the same height. (And because of topography, it won’t be visible from Franklin Street.)

As CHALT notes, this condo building would replace an older two-story commercial building that’s no longer in use, and would be built atop impervious surface. The number of trees that would be required to cut down to build these 56 places to live equals zero. (And the percentage of affordable units in this building is 25%, much higher than we’ve previously seen.)

To save paradise, build on a parking lot

These two preferences—do not cut down trees, and do not build denser development in town—are incompatible, especially here in the Research Triangle, where tens of thousands of people move here every year.

We are a growing region in a growing state in a growing nation in a world with a swelling population. Back in 1960, North Carolina had 4.6 million people, out of a nationwide population of 179 million. In 2020, North Carolina’s population more than doubled to 10.4 million, while the US population increased to 331 million. There are many more people, and many of them are moving here because jobs here are good. In a region and a nation with a housing shortage, they need places to live.

As Patrick McDonough recently pointed out in his excellent piece, “The Fundamentals of Carrboro,” “all the other communities surrounding Chapel Hill and Carrboro have grown by at least 20% [over the past decade], while Chapel Hill and Carrboro have grown at less than half the rate of the others.” This impacts communities outside of Orange County, like Durham, Pittsboro, Wendell, Zebulon, and Morrisville, but also communities in our county, such as Hillsborough and Mebane.

Once we accept that people need to live somewhere, and some of those people will live in Chapel Hill and Carrboro, there are two options. One option is to increase density in already developed areas. That minimizes the need to build new carbon-intensive roads and extend sewer service, and it also means that sometimes when new residences are constructed (like the Berkshire in Blue Hill, and this proposed 12-story building), the work can be completed without cutting down a single tree. The downside for some is that it may affect “neighborhood character” and look out of place.

The other option is to protect areas where people currently live from any change and force all development out into more rural areas, such as those in Wake County, Chatham County, or Johnston County. This obviously requires new and more roads, including monstrosities such as the southern loop of NC-540 that is currently under construction (and that will spike carbon emissions). The type of housing that is built in these areas is almost always going to be separate houses, generally built on land cleared of trees.That’s how you get the type of tree canopy loss that Wake County has experienced, as in this subdivision being built in Apex.

If Orange County did a tree canopy study, we expect they would find similar results: preventing development where people already live only pushes it to the fringes, and leads to forests of trees felled to provide housing for people.

These are our options. We can reuse land that is already cleared of trees and allow new, compact, and space-efficient development like a multi-story residential building in downtown. We can take land that is currently used for single-family homes and allow people to build duplexes, so that two families can be housed on a piece of land that legally could only be used for one, while maintaining most of the tree canopy. That is what Chapel Hill’s new housing policy, adopted in June, is designed to do.

Or, we can insist our neighborhoods and our viewsheds are sacrosanct, and continue what we do now which is allow trees to be cut down for 8,000 square foot homes and saltwater pools so long as they do not change the view of our town from a downtown street corner. And, we can continue to pay little to no attention as large swaths of land miles away are converted from forest to low-density single-family homes—out of sight, out of mind—-until we see an occasional report about trees and the true cost of this sprawling development.

If we could ask them, the trees would probably prefer denser, higher infill development over new tract housing on forested land. But trees don’t get a vote, and the people who say they’re concerned about deforestation often don’t have their best interests at heart.

Author’s note: Four trees along the frontage of the Berkshire site were taken down to build the sidewalk in front of the building, so people didn’t need to walk in the grass or on the street, and after construction finished six trees were planted in its place. TBB regrets the error.