We initially saw Michael Parker West‘s Twitter thread on private school enrollment in North Carolina, and asked him to turn it into a blog post. West is an educator, institutional and community organizer, and assistant principal based in Wake County.

It’s been reported that North Carolina private school enrollments are growing to levels not seen since 1971. And if NCGOP leaders get their way, private school enrollment will grow even more under the proposed expansion of Opportunity Scholarships which seek to remove an income requirement threshold. It would mean that more taxpayer dollars would be siphoned away from public schools and go toward supporting the private school tuition of those who largely already have the means: wealthy, mostly white families. While this may feel like a uniquely modern phenomenon, this story is not new. If you know anything about what was happening with NC public schools in the 1970s, many themes from that era ring troublingly true today. We still have time to change the ending of this story though. The question is whether we will.

Let’s start with a little history.

Most of us know that in 1954 Brown v. Board ruled that separate was inherently unequal, and declared that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. What’s less remembered, is that meaningful compliance with the Brown decision was thwarted for years by the state of North Carolina. Part of that is because racial inequity in North Carolina schools — as Dr. James E. Ford and historian Ethan Roy write — is deep rooted. Our public schools were suddenly charged with doing something they were never originally designed to do: to adequately and effectively serve everybody regardless of background. It’s a fight that continues today.

The NC General Assembly reacted to the Brown decision by passing the Pupil Assignment Act in 1955 which strategically used race-neutral language and empowered local municipalities to prevent desegregation on any meaningful level. According to one report for example, one school district rejected a Black family’s request to transfer their son to an all-white school citing his academic weakness (he was earning mostly Cs) but later disqualified a different African American family’s petition arguing the opposite, saying that because he was earning mostly As, there was no reason to disrupt his academic success.

Even in the 1950s, it seems we white folks insisted our racism had absolutely nothing to do with race.

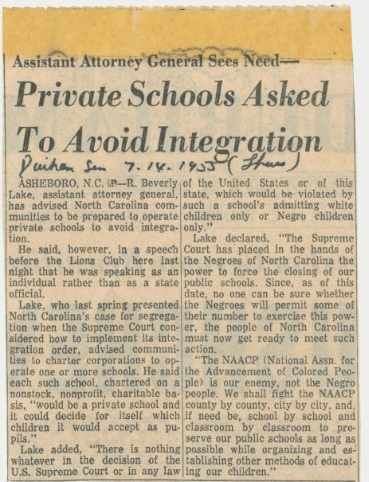

Over the next couple of years, NC passed the Pearsall Plan in both the state legislature and by popular referendum. This began a system of local—not state—control. The Pearsall Plan deliberately decentralized public school authority (in part to prevent lawsuits against the state) and among other things, offered a “freedom-of-choice” provision that allowed white parents to use state money to support their child’s education in a private school.

This is the origin of school vouchers in NC.

By 1961, the state’s strategy of noncompliance was in full swing. Of the 173 public & elementary school districts in NC at the time, all were home to both Black & white families, but only 10 of the districts’ schools even attempted token measures of desegregation.

By the end of the decade however, a series of court cases changed the game. In 1969, Godwin v. Johnston County raised the question of whether NC had an affirmative obligation to actively dismantle school segregation and not simply, as they had been doing, kick it back to the local school boards to figure out. Short answer: yes; the state was on the hook. Dr. Dudley Flood and Gene Causby were hired to help make it happen. Then in 1971, (there’s that year again) Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg ruled that busing offered an appropriate remedy to the problem of segregation. After a full 17 years of delay tactics, North Carolina suddenly had to get serious about actively desegregating their public schools.

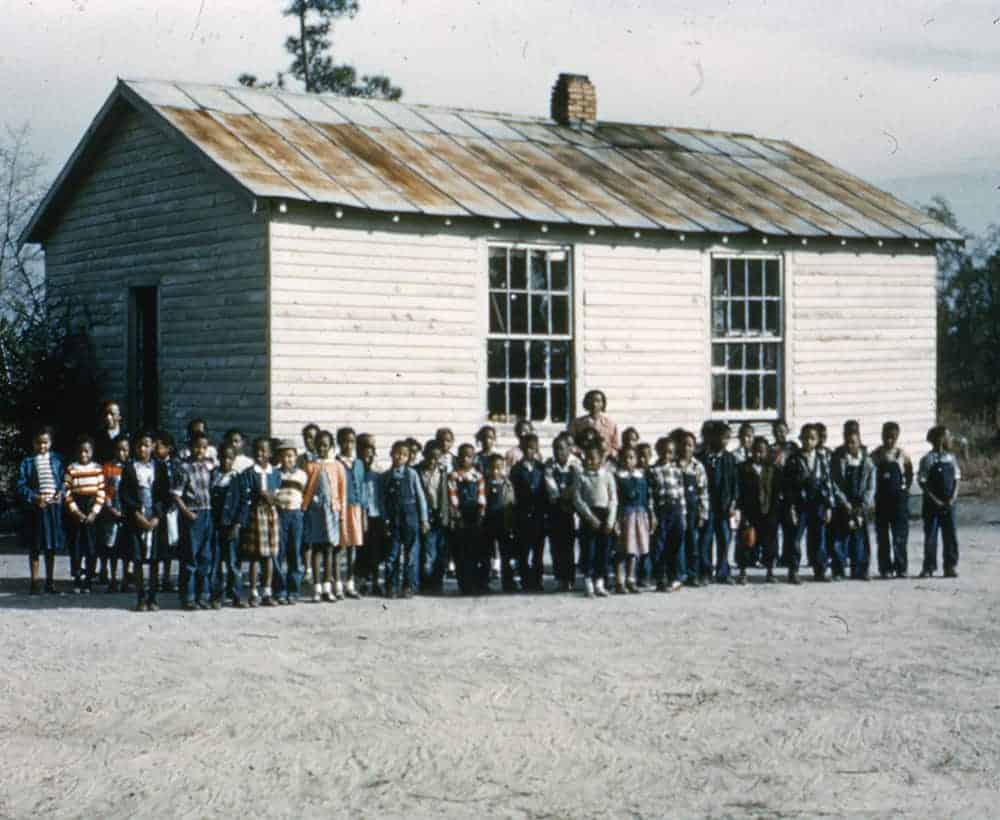

Unsurprisingly, white flight ramped up at an unprecedented rate in response. More than 35,000 white students were enrolled into private academies. Here in Wake County, many of those who couldn’t afford private schools fled the increasingly-Black Raleigh City School system in favor of the comparatively whiter Wake County school system. But when flagship historically white schools in Raleigh began losing programming funds due to the exodus, those with power in the state capital (some of whom had children in those schools) ultimately forced the two districts to merge, forming the modern Wake County Public School System in 1976.

Despite all the resistance however, white students still represented the majority of the public school population in NC for the next four decades. But in the last few years, those numbers have shifted. Students of color now make up the majority of NC’s public school student population. And as districts continue to wrestle with a reckoning rooted in effectively serving everybody, questions about diversity, equity, history, and community are met with a predictable backlash from many of those who have historically expected a measure of exclusivity in our public institutions.

Once again, we see increasing calls to expand school vouchers and state money for private schools, and the active undermining of public schools all across our state. What’s more, it is not uncommon for some of these private institutions to be the subject of high-profile fraud investigations. Many of them have troubling track records of unabashed discrimination in their enrollment practices.

What happens next is not inevitable. The proposed expansion of the Opportunity Scholarship program, particularly with the removal of the income requirement threshold, threatens to divert more $2 Billion over the next decade from the state’s public schools and give it to wealthy mostly white families who are already enrolled in private schools. We still have the chance to do something different this time, but it would require us to take an unflinchingly honest look at how we got here, and the clock is ticking.