For at least six years, UNC Health, the Chapel Hill-based nonprofit medical system owned by the state of North Carolina, has dreamed of turning its ~50 acres of land at Eastowne Drive and 15-501 into a medical campus.

A short history:

In September 2018, the Chapel Hill Town Council approved the first building of the new campus, which required tearing down a few smaller buildings in order to construct a six-story building and a 1000-space parking deck.

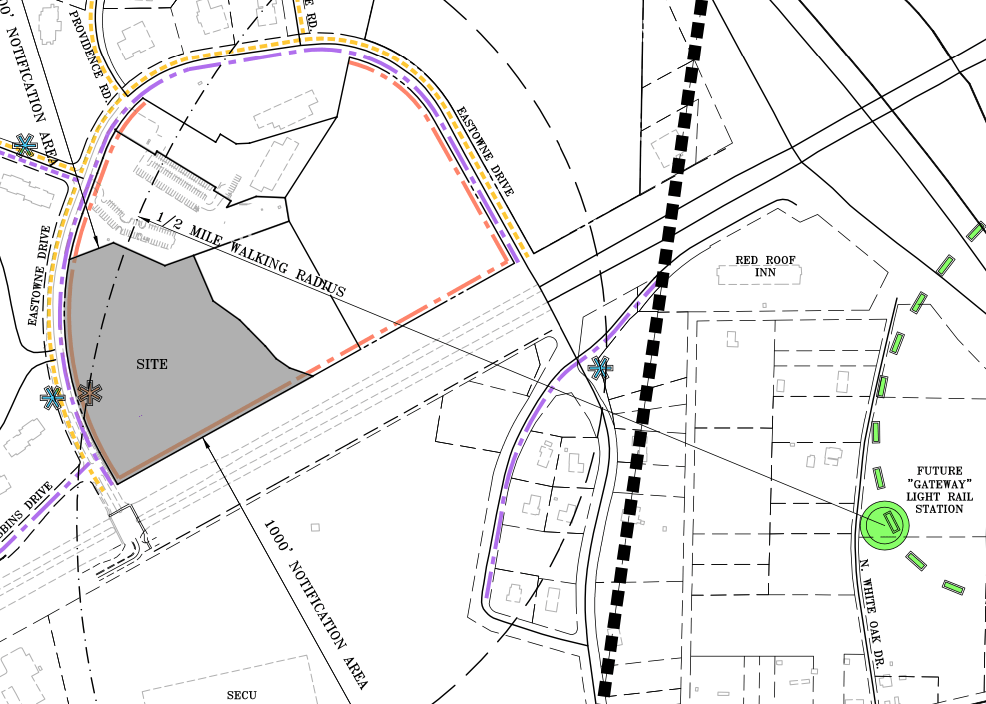

At the time the project was approved, the Durham-Orange Light Rail Transit project was still under consideration, with a planned stop within walking distance of the planned Eastowne campus.

After several rounds of negotiations, UNC Health agreed to lower building heights and eliminate the planned multi-use path along 15-501. (At the time, the majority of council was aligned with CHALT, which supplied the list of demands.)

Duke University & Hospitals helped kill the light rail in March 2019 and, with it, a generation’s worth of land-use planning. Then, a year later, COVID hit.

UNC finished construction of the first building and parking deck in 2021, but the future of the rest of its new campus was uncertain.

With this in mind, one can imagine that the Chapel Hill Town Council of 2023 was happy to see UNC Health come back to the negotiating table in January 2023. UNC appeared ready to get started. They proposed:

- A novel affordable housing plan. Instead of setting aside land for affordable housing, or just contributing money to the town’s coffers, UNC Health proposed contributing $5M to a revolving loan fund that could be used to provide low-interest loans for other affordable housing projects. This is a great idea, and we hope that UNC and the town match UNC Health so we can support affordable housing town-wide.

- But not any money for town services. Early in the negotiations with the town, UNC Health suggested that the council choose between $3M for its revolving loan fund and $30,000 per building in payment-in-lieu per year, and $5M for the fund but no additional money. (As a non-profit, UNC Health doesn’t pay property taxes, but currently contributes a payment in lieu of taxes to Orange County). In the meeting, UNC Health gave the impression that the town opted for the $5M.

Last week, the Chapel Hill Town Council voted to delay its decision on Eastowne. Several council members, including Mayor Pam Hemminger, tried to negotiate on the spot for the town services. In response to Hemminger’s proposal that UNC contribute $4.9 million to affordable housing and $100,000 a year, total, in affordable housing, UNC Health’s Simon George, the system vice president of real estate and development, said, simply, “This is unacceptable.”

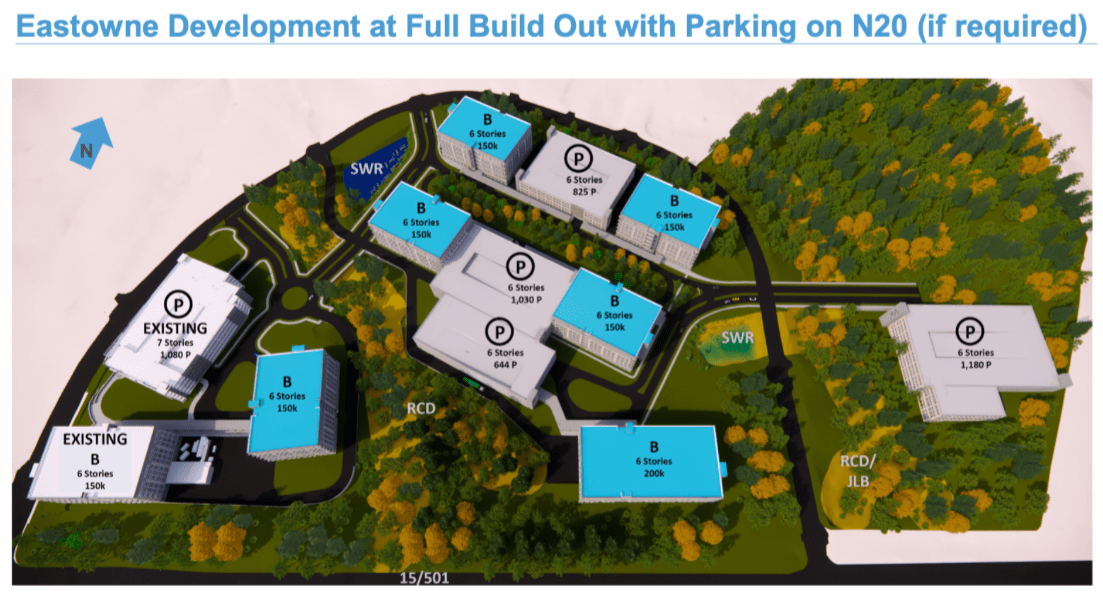

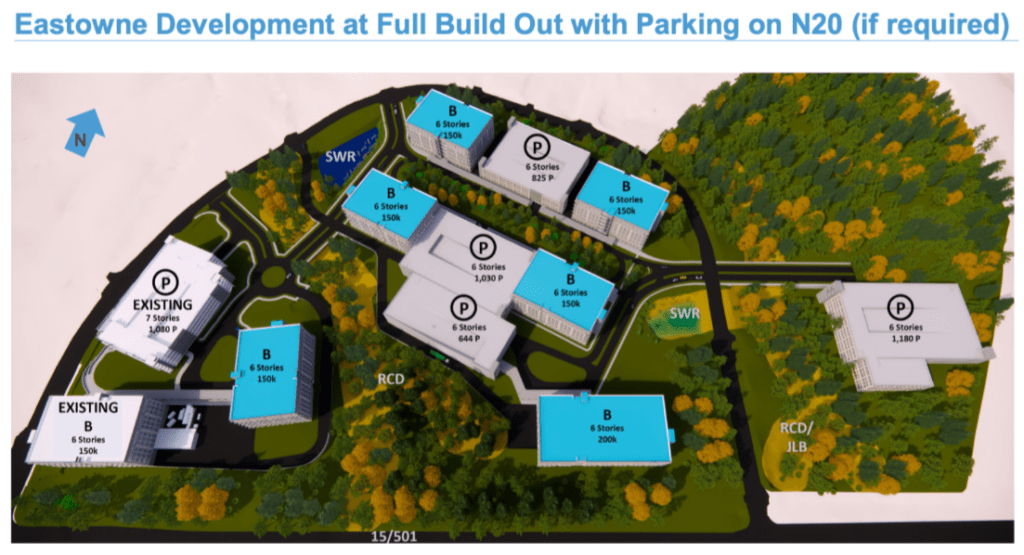

But the biggest sticking point of the night ended up being the one that could have been prevented had the light rail been built—the need to build five parking garages on the site.

As you can see from the map, the campus will be almost half parking decks, all just as tall as the seven buildings. And while the town council earlier spoke about the value of having free parking at the existing Eastowne offices, in contrast to the paid parking at UNC Hospitals, there’s a high cost to free parking, which in this case is the parking garage at the right. (To read more about our local natural experiment in pricing parking, see Ryan Byars’s piece from March).

This deck, if constructed, will be built on what UNC Health is calling the “Northern 20,” part of a wildlife corridor that provides valuable habitat. While this land has long been considered a valuable natural area (previously called “Cedar Trace Bottoms”), the fact that UNC Health needs this land for a parking garage, and nothing else, is particularly egregious. No one, it seems, is happy about this parking garage, but no one has figured out how to make it unnecessary.

Where will people park?

In public discussions with UNC Health, council members have proposed a number of ideas to solve the parking issue, all rejected as being too expensive (building parking underground), logistically unfeasible (building ten- or twelve-story decks, which could lead to congestion and extra time entering and exiting the decks), or just undesirable (like asking employees to park off site and take a shuttle into work).

UNC Health has said that they will only build the deck in the northern 20 as a last resort, if peak occupancy of spaces in its existing decks is 80 percent. (Parking experts note that decks are only to be considered fully occupied if 85 percent or more of spaces are full, and the council should ask UNC Health to adopt best practices for parking demand management.)

But, to my knowledge, they haven’t considered an alternative: charging for parking, which would reduce demand and possibly make the construction of the fifth deck unnecessary. (It would also prevent employees of the UNC Hospitals from using the free parking at Eastowne as a park and ride, which Council Member Amy Ryan astutely brought up.)

While no one likes to pay for parking, in this case the choice the council is likely to have to make is between approving the inevitable construction of a deck on sensitive environmental land in the near future or asking UNC Health to do everything in its power to avoid that possibility, which should include charging for parking. (UNC Health is anticipating taking 25 years to build this campus).

Let’s pay people not to park

There are ways to charge for parking that do not impact low-income employees and patients. For example, UNC Health could provide parking vouchers to patients on Medicaid, and pay employees cash if they choose not to park or carpool together. A recent study by the Federal Highway Administration found that paying employees not to park can reduce parking demand by 10 to 30 percent. The fifth deck represents approximately 20 percent of the proposed parking capacity at Eastowne, so it could be possible to eliminate the need for a deck through this single policy lever.

We should also fund alternatives to parking on site. UNC Health could be asked to contribute more funds to Chapel Hill Transit and Go Triangle to ensure frequent bus service to Chapel Hill, Durham, and elsewhere in the Triangle, which, of course, would include nearby parking lots. With frequent service, taking the bus can be just as fast as driving, as you save the ten or more minutes it takes to park and walk to your destination.

Sidewalks, greenways, and safe street crossings could be prioritized in future planning in the region, connecting UNC Health to housing—and parking—in Blue Hill. For example, if we built a greenway connecting Eastowne to Chapel Hill Crossing, the proposed development at 5500 Old Chapel Hill Road, people could be as close as a 5-minute bike ride or 15-minute walk, and there’s a lot of housing—and parking—that could be built even closer.

In UNC Health’s eyes, perhaps, none of these solutions are as good as building a parking deck on nearby property it already owns. But we shouldn’t let parking demands drive future development decisions. Requiring UNC Health to charge for parking—if not now, eventually—is the best possible solution.