TL;DR: A lot of conversation and debate in our community centers on planning, zoning, and development regulations. But…what are these things? And why are they used? Are they good? Bad? Somewhere in between?

It’s important to understand how land use planning and regulations work, what they can and can’t do, and how they can be used to promote better development outcomes in our communities.

This is the second in a series of posts explaining the basics of planning, zoning, and other land use and development regulations. After exploring some basics, we will exercise your newly acquired planning knowledge by digging into land use issues and opportunities that are more specific to communities in the Triangle.

Did you miss the first post in this series? TBB Land Use & Development Primer | 1.1: Background & History of Zoning

The Legal Foundations of Zoning

Why is the government allowed to tell us what we can and can’t do with our property?

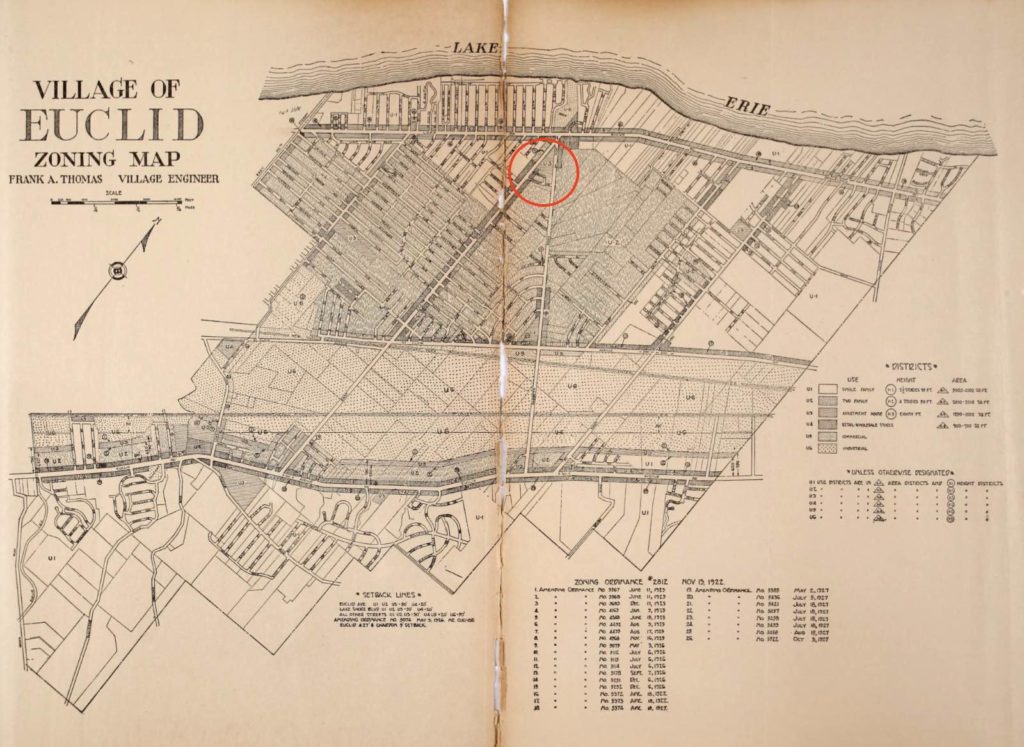

In short, municipal governments are allowed to enact zoning and development regulations (within limits) to keep us safe and protect our health. But, when zoning was first introduced, many people asked the same question. The issue was resolved in the US Supreme Court in the case Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Company (1926). In this case, the Ambler Realty Company owned land in the Village of Euclid, Ohio that they intended to use or sell for industrial development. But, when the Village of Euclid adopted a zoning ordinance in 1922, Ambler Realty’s land was assigned a zoning district that prohibited industrial activities.

Ambler argued that, by enacting the zoning and giving their land a designation that prohibited industrial uses, the Village had essentially stripped the property of its value. This action, they insisted, was a regulatory “taking” prohibited by the Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution (1). Unfortunately for Ambler, the Supreme Court did not agree. The decision upholding a local government’s right to enact zoning states that “If they are not arbitrary or unreasonable, zoning ordinances are constitutional under the police power of local governments as long as they have some relation to public health, safety, morals, or general welfare.” In plain English, this means that if a zoning ordinance or regulation is clearly connected to protecting the health and safety of the community (“public welfare”), it is legal.

Over the years, both zoning and development regulations, more broadly, have been challenged and tested in the courts. Some of the ways that communities have tried to use zoning have been found to be unconstitutional under the Takings Clause, but the government’s ability to enact zoning has not been challenged in the Supreme Court since Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Company in 1926. (Fun fact: this case is also the reason that conventional, activity-based zoning is sometimes referred to as Euclidean zoning.)

This case was like a hundred years ago… is zoning still relevant or even useful?

As American towns and cities changed over the 20th century, and as private automobiles increasingly dominated our land and public budgets, zoning has also evolved. It has expanded to accommodate (and/ or separate) more uses. Many zoning codes now regulate much more than just use or allowed activities. Modern codes include things like setbacks (distance of structures from the street or property lines), lot coverage (the amount of land that a structure can take up), building height (how tall a building can be), and building orientation (the direction a building is allowed to face).

A growing population and the escalating impacts of unchecked suburban sprawl make it more important than ever to be thoughtful about how and where we develop. To do this, we must commit to more sustainable patterns of land use and transportation requiring us to live, work, travel, and recreate in locations that don’t require us to travel dozens of miles at a time in a single-occupancy, fossil fuel powered vehicle. Zoning is a tool that can help achieve these goals.

What is a local government allowed to regulate (and what are they not allowed to regulate)?

Before answering this, we must explain the relationship between the state and local governments in North Carolina. Like so many other things (basketball, barbeque, Cheerwine), North Carolina is also special in the ways the state allows local governments to enact regulations. Local governments (like towns and cities) are always creatures of the state – formed and dissolved in the image of their maker. In some states, local governments enjoy greater latitude to make their own rules and regulations. We call this arrangement home rule. But, in other states, local governments are much more limited. In these states, local governments only have the powers that are expressly delegated to them by the state. We call these Dillon’s Rule states (so named after one Judge John Forest Dillon, who sealed his fate when he was the first to apply a rule testing the limits of local government).

Most states clearly fall into one of these two categories – home rule states or Dillon’s Rule states. North Carolina, however, does not neatly fit into either box. And this is where it gets a little complicated. So, if you’re confused (or just don’t care), the key takeaway is that North Carolina is not a home rule state, but we don’t apply Dillon’s Rule either. (Skip to the next section if you can live without knowing why.)

Instead of using Dillon’s Rule to test the powers of local government, North Carolina claims to use something called the “plain meaning” rule to determine the powers of local government. This rule is is supposed to enable a broader interpretation of local government power. But, as experts point out, this rule is not applied equally in all decisions. Instead, the state is using an interpretation of local government power that is even more strict (i.e., more limited) than Dillon’s Rule allows. And local governments (and planners… and residents) are left to untangle a confusing web of individual statutes to try and figure out what’s allowed and not allowed.

Okay…that’s confusing. What are local governments in North Carolina allowed to regulate through tools like zoning?

The following types of development regulations fall within the local government’s power to regulate (in North Carolina):

- The ways property can be used (residential, commercial, home-based businesses, small businesses, healthcare, aging support services, etc.)

- The types of housing that can be built on a property (duplexes, condominiums, single-family, retirement homes, small apartments)

- The location of a building on a property (building placement and orientation)

- How tall a building is allowed to be (building height)

- Minimum and/or maximum lot size

- Commercial and multi-family residential aesthetic design

- Requirements for sidewalks and landscaping

- Requirements for bike parking

- Requirements for open space (like parks and community areas)

- Requirements for greenway/trail development in new subdivisions

- Requirements for street connectivity in new subdivisions.

Are there things local governments in North Carolina are NOT allowed to regulate thorough tools like zoning?

Definitely. In North Carolina, development regulations like zoning cannot:

- Regulate single-family home design (number of bedrooms, garage placement, style, etc.)

- Regulate the cost of a home (through zoning alone)

- Require that businesses are locally-owned

- Require landowners to develop their land

- Prevent landowners from developing their land in ways that are allowed by-right (described in upcoming sections).

That’s enough zoning for today. In the meantime, dust off your safety goggles and PPE. Because, in our next installment, we will dissect a zoning ordinance.

(1) The Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution prohibits the government from taking private land for public use without just compensation (this is called the “Takings Clause”). The US Supreme Court differentiates between physical takings (i.e., the government seizing your land) from regulatory takings. The “regulatory takings doctrine” was established in Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon (1922) when the US Supreme Court ruled that takings can result from regulations “going too far.” This concept of “going too far” was further tested and clarified through subsequent cases including Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City (1978); Agins v. Tiburon (1980); First English Evangelical Lutheran Church of Glendale v. County of Los Angeles, (1987); Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council (1992); City of Monterey v. Del Monte Dunes, (1999); Palazzolo v. Rhode Island (2001); Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning (2002); Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A. Inc. (2005);and Murr v. Wisconsin (2017).