The Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University recently released its 2023 State of the Nation’s Housing report. The report offers timely analysis of a variety of topics related to housing supply and affordability.

Here are some findings from the report that may be of interest to our readers, especially as we approach an election in which housing needs (or the perceived lack thereof) are certain to be a key campaign topic. All figures are from the report. See the report for data sources and methods.

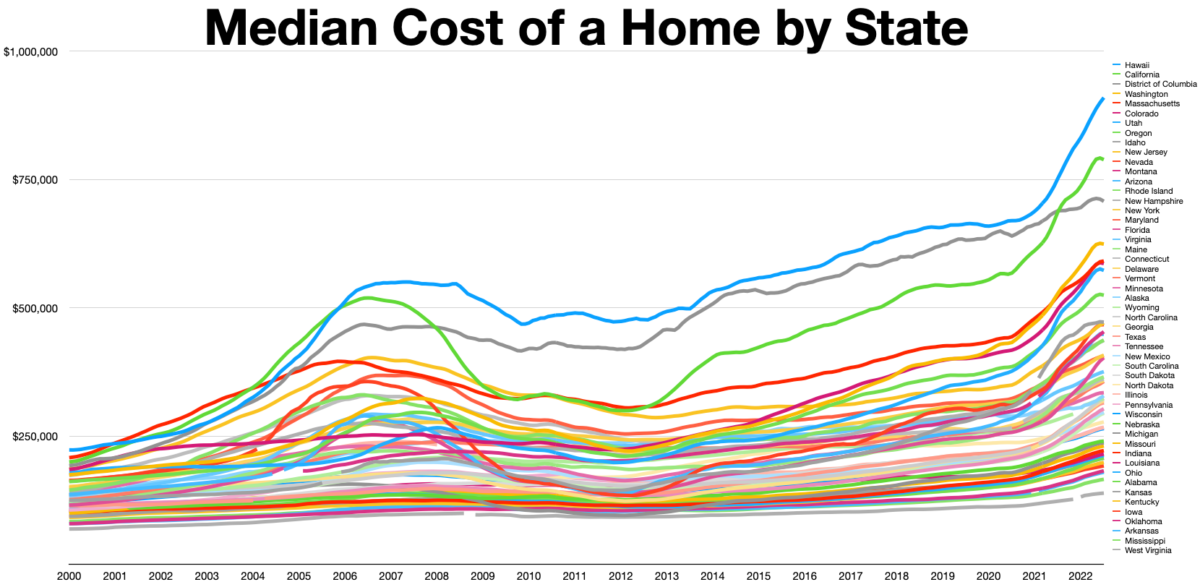

Year-over-year growth in housing costs has leveled off

Housing is still too expensive for many renters and homebuyers, but at least the rapid price increases seen in the first year of the pandemic have abated.

New single-family construction is below the historic average, multifamily above

It remains to be seen if the U.S. will ever build single-family housing again like it did before the Great Recession (whether and where it should, given the climate implications of low-density, car-oriented development, are separate important questions).

As we’ve said many times on TBB, we don’t build starter homes anymore. According to the report, “The decline in new homebuilding is particularly acute for lower-priced homes, due to rising construction and land costs, limited lot availability, and regulatory barriers like minimum lot sizes that restrict entry-level housing production.”

Multifamily housing construction has exceeded historical averages since roughly 2014. As feared by many in Chapel Hill, “the bulk of new construction targets the higher-cost market segment.” But the report also notes that the surge in construction and rising vacancy rates will likely limit rent growth rates for that segment. More new multifamily units affordable to moderate and lower income households (including market-rate and subsidized units) are needed to meet demand.

Rent growth has slowed

This bears repeating because some people in Chapel Hill – included several running for mayor and town council – do not believe housing is subject to the laws of supply and demand. Rents are still too high for many households, but a slower rate of rent growth is a good thing (unless, perhaps, you are among the many small landlords in Chapel Hill who rent to students).

People increasingly moved to small metros like Durham-Chapel Hill during the pandemic

The report’s authors speculate that the rise in remote work during the pandemic encouraged younger workers to leave large cities in the Northeast and California for more affordable locales: “Between 2019 and 2021, the share of the workforce reporting that they usually worked from home tripled from 6 percent to 18 percent. Among younger workers ages 25–34, rates of working from home more than quadrupled from 4 percent to 18 percent. Given that younger adults have the highest mobility rates and that remote workers were more likely than commuters to move, the increase in working from home among younger workers likely contributed greatly to the recent rise in interstate mobility.”

Over a quarter of all households are headed by someone 65 or older

The last decade has seen a surge in households headed by Boomers and, to a lesser extent, Millennials. A rise in aging households that want to age in place presents a range of challenges to places like Chapel Hill where many homes are large and expensive to maintain, lack accessibility features, and are isolated from goods and services for people unable to drive. According to the report, “demand is increasing for smaller housing, accessibility features such as single-floor living, and services delivered to the home. At the same time, increases in multigen- erational households are driving interest in flexible housing designs spacious enough to accommodate larger family households.”

Exclusionary zoning contributes to a higher share of people of color residing in high-poverty neighborhoods, regardless of income

Households of color in America have fewer housing choices available to them than white households. The share of Black households earning $75,000 or more living in high-poverty neighborhoods is roughly the same as the share of poor white households in those neighborhoods. And exclusionary land use policies are a significant contributing factor: “In many cities and suburbs, zoning favors single-family homes, which are typically owner-occupied and more expensive than multifamily options. This limits opportunities for households and renters with lower incomes, many of whom are people of color.”

Rent burdens are approaching historic highs

From 2019-2021, the share of cost-burdened renter households (those paying 30 percent or more of their income on housing) increased to 49 percent of all renter households (In Chapel Hill, 56 percent of renters are cost burdened, according to Census data). When renters are cost burdened, they may sacrifice on other needs: “households with lower incomes may struggle to pay for other necessities like food, clothes, and healthcare, which have become more expensive as inflation has risen.”