What makes a place conducive for human happiness and wellbeing? And how do we create that in the face of our sustainability challenges?

“And what are our needs for happiness? We need to walk, just as birds need to fly. We need to be around other people. We need beauty. We need contact with nature. And most of all, we need not to be excluded. We need to feel some sort of equality.”

Enrique Peñulosa, the mayor who transformed Bogatá, Columbia with a goal of happiness

I’ve spent decades of my environmental career focused on sustainability, and especially community sustainability, on top of training in applied ecology. When you take all that information, put it in a head like mine, add a fascination with “happiness” following a divorce, and mix it up really well, the answers to those questions start settling into a reassuring picture. The upshot is, the same community structures and actions needed to create sustainable communities will also foster our happiness and wellbeing. Isn’t that handy?

One problem in convincing folks of that is that human beings are notoriously bad at predicting what WILL make them happy. Some people think: a bigger salary, a bigger house, a hot spouse, a hot car… But we’re usually wrong. For example, work hours have gone down since 1965, but with more time spent watching TV and less socializing with friends, we have less satisfaction. In fact, doubling one’s number of friends has an equivalent effect on well-being as a 50% increase in income.

To paraphrase Derek Bok in The Politics of Happiness, once the necessities and comforts of life are met, happiness doesn’t seem to come from selfish pursuits, but primarily from having close relationships with family and friends, helping others, and being active in the community, i.e., those things that contribute to a better, stronger, more caring society. At the same time, happy people tend to live longer, enjoy better health, work more effectively and contribute more to strong, effective democratic government and flourishing communities. So, having happy people around is all kinds of good.

I think that everyone’s rush to gather with friends “post”-pandemic proves how much social relationships mean to us. Sadly, the way we’ve lived post-WWII has made that much harder. As American neighborhoods sprawled out, people watched more TV and two-career families expanded, less and less time was available for such socializing. The result has been an erosion of social capital — that social connectedness which is so valuable to human existence.

In Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam talks about how, where social capital is robust, children learn better, stray to crime less, and thrive more. Old people with high social capital had higher survival rates in heat emergencies — neighbors were watching out for them. But when we live more apart from each other, when we spend too much time in commutes (the specific activity with the worst impact on happiness), it’s harder to arrange socializing – like those old bowling leagues and clubs where community ties, both strong and casual, made society stronger and inhabitants happier.

Conversely, isolation is unhealthy, associated with poor mental health and unhappiness. Yet more and more people are living in isolation as our housing is spread out, we don’t know our neighbors, and we’re increasingly living in one-person households. As a divorced empty-nester, I LOVE it that I can walk four blocks tonight to gather at a restaurant for the monthly bike alliance meeting – it feeds my well-being even though I’m introverted.

The specific activities that make people happiest are #1, a loving relationship and #2, socializing after work. Watching TV, which most of us spend our evenings doing, is only #9 of 18 evaluated.

A local government can’t do much for your #1, but it can create places that foster #2. So, a place that is dense and well-designed enough that people don’t have to commute alone in a car from door to door, but, instead, can run into friends on the way home for a beer or dinner, is a happier place. It has also been shown that places with sufficient density for such accidental interactions are also more economically productive and creative.

As Peñulosa described, human beings also innately love nature. It calms us. We universally recognize its beauty. The Japanese have institutionalized walking amongst trees for health as “forest bathing.” So, density without ample AND equitable access to nature is inadequate for well-being.

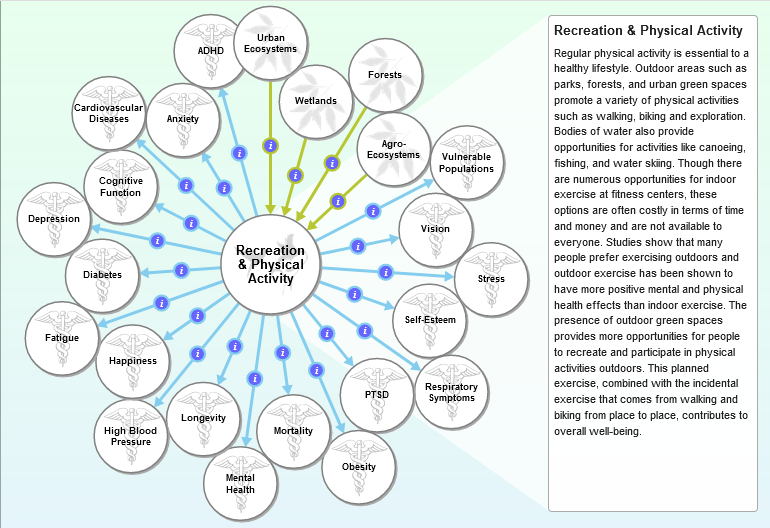

A great US EPA tool, the EcoHealth Relationship Browser, has summarized data showing how different ecosystems foster a multitude of health benefits – all of which means that we save money on health care costs and gain from greater productivity.

Charles Montgomery, in Happy City, tells of one example study where a lack of greenness in the courtyards of affordable housing complexes led to more crime, regardless of their upkeep — and the less green, the higher the rates of violent crime. Nature deprivation is not only unhealthy, it’s dangerous, because it leaves people feeling more raw and aggressive. It also leads people to abandon barren spaces, removing watchful eyes. Green spaces build social capital by fostering hanging out and hanging out fosters chatting. Humans especially like biodiverse greenscapes, with many different kinds of trees and birds, the more diverse the better. So, the sterile lawns and token trees of sprawl are “empty calories” of nature. Even tiny splashes of nature create a psychological ripple effect, so cities need accessible greenspace for everyone in sizes S, M, L and XL.

Trees are also incredibly helpful in helping cut the urban heat island effect where the concrete of a city holds the day’s heat. This exacerbates heat weather emergencies, as we lose the cool respite at night we need to recover. Shade trees, especially along streets, shade hard surfaces while also catching some of the rainwater that causes stormwater issues.

Which takes us to stormwater issues. Some believe that the taller buildings that density requires means worse stormwater problems. In fact, the sprawl form of housing is a far bigger culprit for stormwater issues, because it means more trees destroyed and impervious surface area PER PERSON than density. Sprawl also means that, despite most trips being less than 3 miles, all trips need a car, so we need more impervious roads and parking lots.

Sprawl makes car alternatives, like transit and walking/biking/rolling infrastructure, harder to provide. And sprawl form doesn’t just occur in suburbs, but in a town’s older, more diffuse neighborhoods. Density that allows us to meet our needs without a car is more equitable, since not everyone is able to drive or even afford a car. Also, greenway bike/ped infrastructure allows for emission-free transportation that provides healthy greenery, exercise and recreation, wildlife habitat, and connectivity for pollinators, as well as people!

I mention stormwater in an article about happiness and wellbeing because environmental issues, like floods, pollution, habitat loss, and the anxiety and impacts of climate change and species extinction fall into the “creating unhappiness” side of the ledger. If we do not address these issues, we negate our Happiness-inducing actions and we won’t preserve even the basics of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Physiological needs (like drinkable water and food) and Safety needs (like health and resources). If we do not fight climate change, habitat destruction and extinction of species like pollinators, we are, to be blunt, screwed. But how do we fit these issues into one of community happiness?

Well, here is where the confluence of all these issues occurs – where actions for one will support benefits for the other. A happy, sustainable community will be dense, but not crowded, with green everywhere in small, medium, large and linear arrangements. It will have daily needs within 15 minutes, where we can bump into friends and acquaintances to have fun or be creative. People can pick up a coffee and Danish while walking to transit, read or chat while they commute, then walk home by way of a shop or a pub. There are parks that catch and treat stormwater, where kids can play and grownups can birdwatch, people watch or play. There are many opportunities to build social capital, so that kids are healthy and learning well, citizens are engaged and working for the common good, and we are all watching out for our friends, our neighbors, and our government. Luckily, it’s also cheaper to build and maintain that kind of city, many of the benefits translate into economic productivity and a higher functioning workforce, and we save money on gas, doctor bills, and therapy.

In short, when we build a sustainable community, we sacrifice nothing that we really need for our wellbeing and we preserve that which we do.