The federal low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) is not well understood, but is responsible for more than $1 billion of new real estate activity in North Carolina each year. Currently the state has more than 1,200 properties containing 70,000 units in almost every county, yet odds are hardly anyone reading this post can name one.

How did the LIHTC get its start?

Congress enacted the LIHTC in 1986 as part of tax reform. Since then it has grown in size, sophistication, and support to a degree unmatched in the history of American affordable rental subsidies. There are multiple reasons why, but ultimately it’s because the fundamental model works remarkably well.

The first step in understanding is seeing how the program relates to other activities. The matrix below separates out the how – demand versus supply-side interventions – and who is served.

| Tenants | Owners | |

|---|---|---|

| Demand | Housing Choice Vouchers (“Section 8”) | Down payment assistance, below market interest rates |

| Supply | LIHTC, public housing | Habitat for Humanity, community land trusts |

Although LIHTC properties are only rental, they can take any form, from single-family houses to steel-frame high rises (the vast majority are somewhere in between). Developers can construct new buildings, rehabilitate existing apartments, and/or adaptively re-use existing structures. The developments are very high quality, similar to or better than market-rate.

Affordability Through Equity

Next is understanding the affordability mechanism. In very basic terms:

- Financial institutions (primarily banks) invest equity; their return is from tax benefits, not rents.

- This equity means less debt financing and resulting payments, which makes lower rents possible.

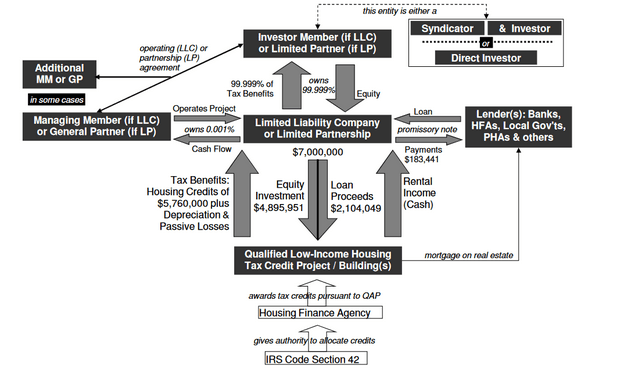

This image depicts the structure of the ownership entities, and this corresponding hypothetical demonstrates the investment calculation (some numbers are now out of date).

Why Use the Tax Code?

Again, the previous paragraph is very much a summary. There’s a lot more to the story, which brings us to the step of answering a frequent question: Why create such a complex system instead of just appropriating funds? (Note those other programs are also quite complex.) An often-expressed reason is the value of public-private partnership.

However, experienced practitioners know the real key is the boring concept of compliance: programs succeed or fail to the extent participants follow the rules. Using the tax code allows for a uniquely effective form of enforcement.

- The equity provided up-front is based on a presumption that the investor will receive all the anticipated LIHTCs.

- Upon finding noncompliance, the state allocating agency sends a report to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

- The IRS reduces the amount of LIHTCs generated that year (how much depends on the severity).

- The investor imposes a financial penalty on those responsible for their inability to claim the already-paid-for tax reduction.

- From a tenant perspective, the only consequence resulting from these actions by the state, IRS, and investor is the problem gets solved.

The possibly in #4 means owners and property managers are very motivated to comply. By contrast, while absolutely necessary, appropriations do not benefit from the same feature. Essentially all serious consequences for noncompliance are worse for tenants than owners (e.g., ending assistance), which means agencies must think twice before imposing truly effective remedial measures.

What are the federal standards?

Last at the general level are the federal and state rules. Both have requirements for the maximum LIHTCs awarded and ongoing operations. On the latter, federal law and IRS guidance mandate owners

- limit occupancy to households below certain area median income percents (mostly 60%),

- charge rent affordable to those income percentages, and

- properly maintain the units/buildings,

for at least 30 years. (There are wrinkles to the above, like for students.) The rules for a state are more varied and detailed.

How is this implemented in North Carolina?

Although a federal resource, administration of LIHTCs happens mostly on the state level. The main policies are in qualified allocation plans (QAPs). The North Carolina Housing Finance Agency (NCHFA) administers the program according to the QAP in effect for a particular calendar year.

The initial and highest-profile aspect is setting the terms of a competition. For context, the 2022 round started in January with 127 applications and ended with 28 awards for totaling 1,716 units. Another form of LIHTC accompanies properties using tax-exempt private activity bonds (PABs). This resource is not oversubscribed because of being more challenging to use (less tax subsidy and greater transactional costs). The January 2022 round produced 23 awards containing 2,713 units using PABs.

Current Qualified Allocation Plan

NCHFA’s 2023 QAP separates the state’s competitive LIHTCs into five distinct contests, known as set-asides:

- one with 10% of the total for rehabilitation of existing housing, and

- the rest for new construction split into four geographic regions – Central, East, Metro (the seven largest counties), and West – based on their per-capita share.

Orange County is in the Central Region. Another contest is within a county: other than the Metro, each is limited to one new construction award.

Applications need to meet numerous threshold requirements to be eligible. One of the most relevant to this post is that all legislative and quasi-judicial zoning approvals must be complete by mid-May (developers usually start the process in January or February). There are no waivers or exceptions. Considering the 4:1 application/award ratio, if an application does not meet a requirement, NCHFA will just move on to the next in line.

Within each set-aside, and in some cases county, NCHFA ranks eligible applications using selection criteria. For most categories all developers can earn the maximum possible points. An example is distances to amenities; if a grocery store, shopping, pharmacy, and more are not within 1.5 miles, the site won’t compete.

An exception everyone earning the maximum score is the state Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has identified 12 Central, East, and West counties (including Orange) and all in the Metro as being a priority for awards, so applications there earn an additional point. Since 2002 NCHFA has partnered with DHHS to target 10% of units in LIHTC properties to persons with disabilities.

How is Orange County doing?

So how is Orange County doing with the competition and PABs? The only answer is relative to others, and Buncombe County is a good comparison. The fundamentals there are more difficult considering the mountainous terrain, tourism-based land costs, and extent of park land.

- Buncombe has 3,023 LIHTC units for its population of 271,534.

- If Orange experienced the same level of production over the years for its 148,884 residents, it would be home to 1,658 units.

Instead, despite the relative advantages, there are only 720, of which 124 are in a single 26-year-old development. For another comparison, Wilson County has roughly half the population and 1,224 units.

Why did this happen?

There’s one simple reason: the jurisdictions’ well-earned reputations for difficulty, especially Chapel Hill, is a strong deterrent to developers looking for opportunities. In other words, area localities’ land use policies caused thousands of people to miss out on affordable housing. Deliberate, ongoing choices are producing entirely predictable outcomes.

The good news is elected officials have the power to change their perceptions and realities through swift, effective actions. A great start would be ending the ban on apartments applicable to most parcels (as in going much farther than the current “missing middle” proposal) and completing discretionary processes in three months.

All it takes is political courage.