In the Facebook thread that just won’t quit, we’ve moved on from discussing whether newly-built apartments in Chapel Hill generate enough tax revenue to pay for services they receive (Spoiler: Yes.) and onto a series of other discussion points, including:

- Whether we can and should apply the fiscal analysis for the not-built 2014 Obey Creek project to Blue Hill to predict costs

- What kinds of development generate positive revenue for Orange County

Facebook is starting to break for us under the number of comments in this 160+ comment discussion, which is unfortunate or fortunate depending on your point of view.

So we’re taking to the blog. We first want to say that we hate that we even have to have this conversation. It’s yucky—and as Pat Dugan writes, “The fiscal structure of local government is not based on matching income streams with service costs by land use. Generally, local governments exist to serve people irrespective of where they live, play, shop, work, travel, or visit within a jurisdiction.”

We wrote our initial blog post to counter a dogged and ugly misnomer that persisted, unchallenged, for a decade in our community, and thought the conversation would end there.

But here we are.

First, we don’t think it’s a great idea to apply the fiscal analysis for the failed Obey Creek project to the Blue Hill District for the following reason:

The 2014 Obey Creek fiscal analysis didn’t differentiate housing types when it calculated cost of services

The 2014 Obey Creek fiscal analysis doesn’t outline its methodology, but a Facebook commenter noted that it calculated cost estimates for services by doing some back-of-the-envelope math: by dividing each cost category’s current budget by the population of Chapel Hill. If that’s the case, then people in single family homes were treated the same as people who lived in apartments, who were treated the same as students at UNC. In a formal fiscal analysis, people who live in detached houses are assigned different cost values for services than people who live in apartments. This is because in Chapel Hill, people in multi-family units are less likely to have kids in the school system and the infrastructure costs are lower and things like that.

The 2014 Obey Creek fiscal analysis was for a proposed Southern Village-like new development with 18 retail units, 5 offices, 1 hotel, and 673 housing units (of different types) spread over 130 acres. Blue Hill is a completely different project. Apples to oranges.

The proposed Obey Creek development was new—so nothing existed (or exists today) on the land. The proposal included a hotel, retail, some single-detached houses, and some condos. And because it was “greenfield” development, it included a lot of new water, sewer, utility, and road infrastructure. The apartments in Blue Hill are largely infill, meaning they’re built alongside already-existing infrastructure and replaced things like empty parking lots and chain-linked fences. Infill development can take advantage of existing services and infrastructure. For example, an analysis of 29 Minnesota counties found that overall per capita cost for county-owned and -maintained roads tends to decline as the percentage of people residing within that county’s cities increases.

This may be obvious, but applying an eight-year-old fiscal analysis from something that wasn’t built to a bunch of different things that were built as infill is not accurate.

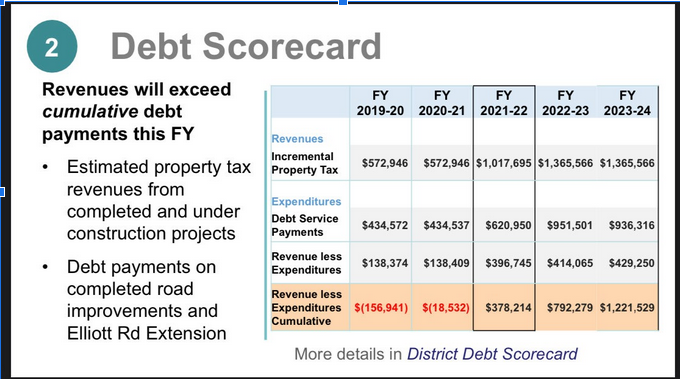

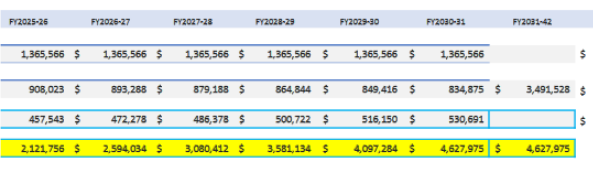

You can see the revenue and expenditures for the Blue Hill district on the town’s progress page. (They publish a report card each year.)

The tax revenue from the Blue Hill district goes to stuff that benefits everyone

When the Blue Hill district was formed, the Town invested money with municipal bonds to be repaid over 20 years with tax revenue from the Blue Hill district. Those bonds have been used to pay for stuff like new public roads to traffic improvements to stormwater management improvements.

Meanwhile, the property tax valuation of all properties in the district has gone from $154 million in 2014 to $302 million in 2020 — and they use very little in town services.

Revenues started to exceed cumulative debt payments in fiscal year 2021-22:

And you can see that it is projected to bring in more tax revenue for Chapel Hill in the coming years. (The last line is (revenue – cumulative debt obligation.))

(This doesn’t include school and Orange County taxes.) The new apartments in Blue Hill are very good for the town’s finances. Take, for instance, the Berkshire apartments near Whole Foods. They are assessed at $82 million, have near-zero children in public school and consume almost no county services and very few town services. And for the past four years, they’ve been the number two taxpayer in Chapel Hill.

Elliot Road Extension is a public road

One CHALT talking point is that the Elliot Road Extension is a private road — this, too, came up in the Facebook thread. It’s not – it’s a public road projected to carry 7,800 cars per day, far more trips than the Park Apartments will generate (the developer also contributed $1.5 million to the town for affordable housing). Once it’s built, people on the east side of Chapel Hill will use it to get to Whole Foods—and the Chapel Hill Public Library. It will be one of the town’s most bike-friendly roads and a key link in our growing bicycle trail network.)

Which brings us to the Orange County analysis by Tischler-Bise

In February 2022, Tischler-Bise presented a fiscal impact model of Orange County to the Board of Commissioners. The model makes some assumptions about housing types in Chapel Hill—and it does differentiate single-family homes from multi-family units.

However, in the model, all multi-family units in Chapel Hill are treated exactly the same, when we know that new apartments have different costs (and revenue) than older apartments. The cost of infill development—which takes advantage of existing infrastructure—looks very different than the cost of new development that requires new water and sewer lines. Multi-family units that house senior citizens require different levels of services than those that attract students. (The former, for example, has more medical/EMS costs; the latter may take the bus to campus.)

We hope that the forthcoming fiscal impact analysis of Chapel Hill provides more nuance—and accounts for our large student population, which may be likely to obtain services on campus rather than from the town.

We consider schools and libraries and roads and giving our town staff much-needed raises (and possibly therapy!) a public good

This type of fiscal analysis – which is primarily based on property tax – also overlooks that we collectively finance services for the entire community. We all pay taxes to benefit our school system, even if some of us don’t have kids in school. We consider that a public good. We all pay for fire and roads and infrastructure updates and libraries. These are good things that we collectively need and that help our community, and actual costs will largely be made by real operational considerations rather than the abstract.

Boiling everything down to a model that breaks everything down to property tax will inevitably favor more expensive, existing homes. People who put together fiscal impact analyses warn against using “more expensive things” to make decisions for the whole, because that can lead to support for exclusionary zoning.

And these—we should note—are models. What we do know from actual data is that even a decade ago, for every two dollars in expenses attributed to large multi-family residential complexes, the Town of Chapel Hill was getting somewhere between $5.50 and $7.70 back in revenue.

Models can only say so much. They make assumptions about data based on a point in time. That’s useful, for that point in time — but it may not be accurate for the future.