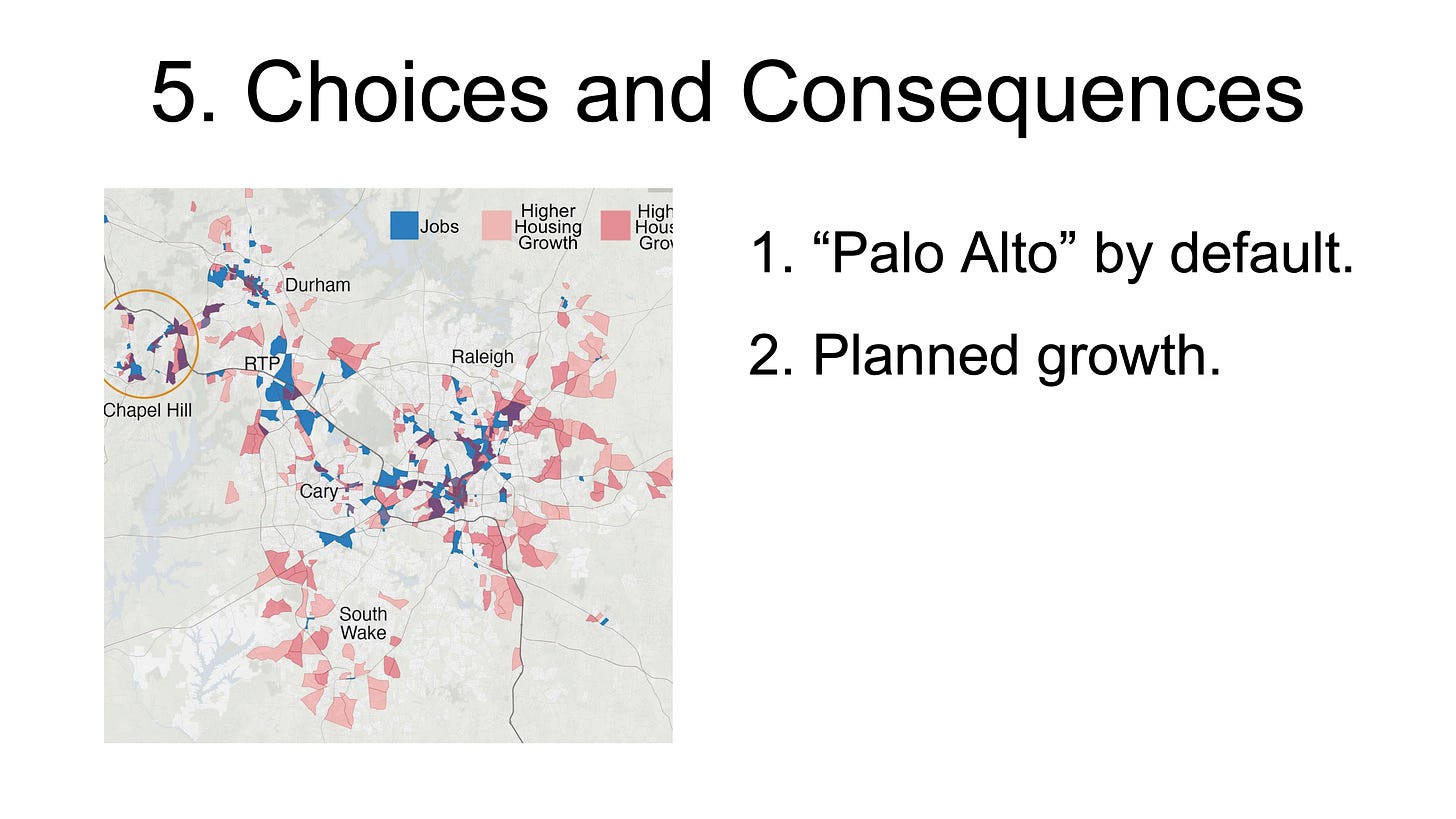

Calling Chapel Hill a town on the verge of becoming an exclusive enclave of wealthy homeowners, an East Coast “Palo Alto,” a real estate consultant issued a blistering report about Chapel Hill’s direction, finding that the town needs to build significantly more housing to moderate housing price increases and retain our economic competitiveness, and criticizing how we do development.

This report puts the lie to the claim by some that Chapel Hill is simply growing too fast. There’s little evidence of that, and the report states that the town is going to need to build substantially more housing over the next 20 years if it wants to remain a diverse, interesting, and affordable community. At least 495 units of housing are needed each year over the next 20 years to accommodate projected demand — that’s the amount of housing included in the Carraway Village project that’s taken countless hours of council meetings and many years to come out of the ground, every single year. Without more housing, our economic development efforts will hit a roadblock, as it simply won’t be competitive for far-flung workers to commute to Chapel Hill when they will have other, closer, good-paying options.

This study was commissioned by the Town of Chapel Hill and UNC-Chapel Hill, and a full report is due in the next few weeks. The consultant, Rod Stevens from Business Street, presented his findings to Chapel Hill Town Council members last Friday (Sept. 10) at a meeting of the Council Economic Sustainability Committee. And Rod did not hold back, telling council during a hour-long presentation that local government’s choices over the last 20 had led the town into a bad place, and that real leadership would be needed to get the town out of this mess.

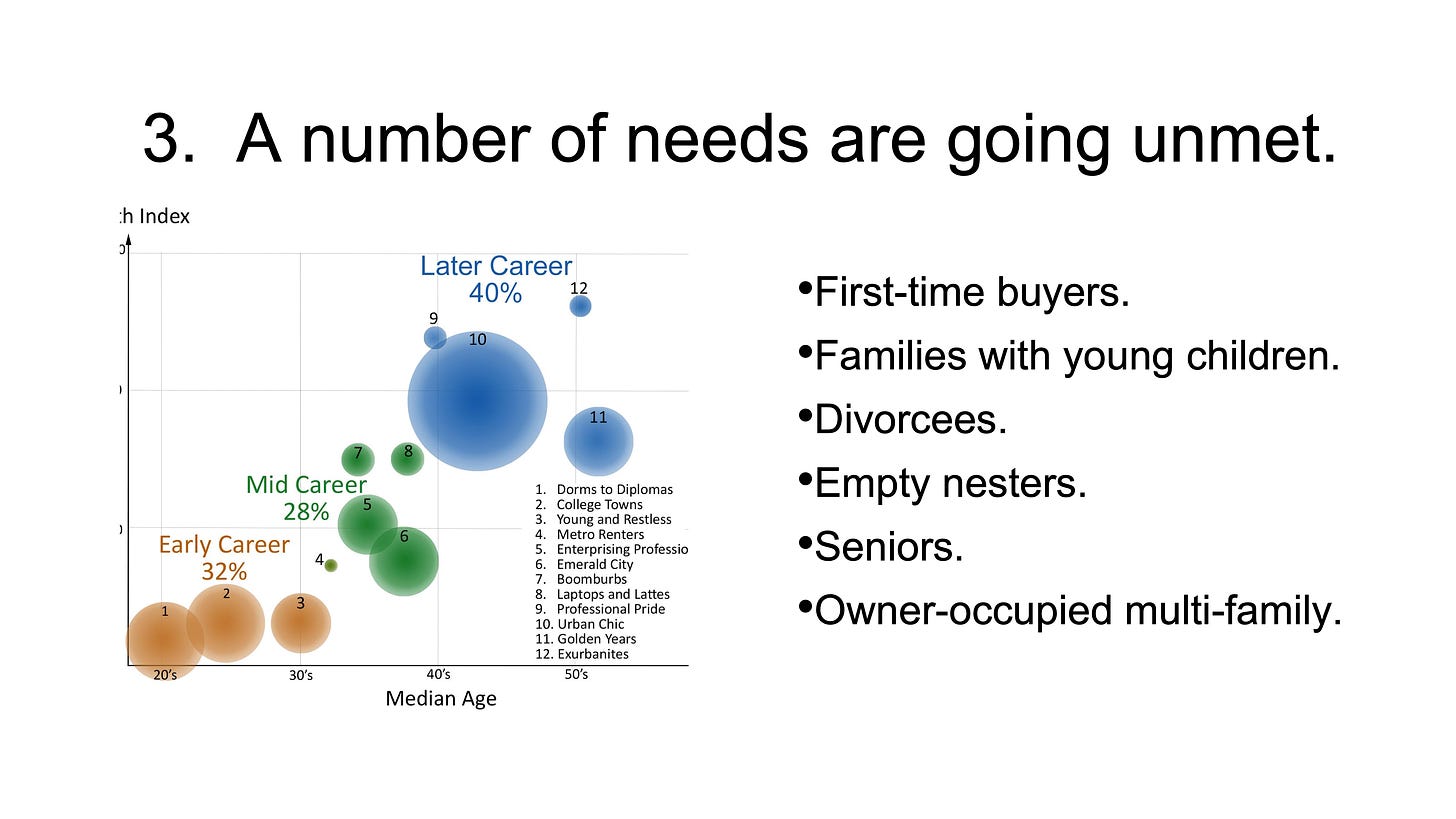

The problems with Chapel Hill’s housing market, Rod noted, have little to do with students. Instead, it’s driven by the fact that Chapel Hill is a nice place to live with good schools and one big job cluster at UNC. It’s a university town with, increasingly, only housing for those with higher-paying university jobs. There’s some housing for students, and much of the rest of the housing is occupied by dual-professional households with jobs in Durham and Raleigh (or, presumably, remote) and with kids. What’s missing are options for most other market segments — what he called a “missing middle” of age and lifestyle options. Those shut out of the housing market include:

- First-time homebuyers who can’t afford single-family homes. The town lacks enough condos or townhomes to provide realistic ownership opportunities for these people, and so they move elsewhere. (I’ve got a friend who did just that, leaving Chapel Hill after more than a decade renting here to purchase a townhome in Durham).

- Homes for families with young children, which in this area are largely restricted to detached single-family residences due to the lack of good public amenities.

- Empty nesters, who don’t have the type of multi-family options to live in that are available in other areas.

- Housing for seniors, exemplified by the 15-20 year wait list at the Carol Woods retirement community.

Also squeezed out are the type of people with middle-income jobs, such as administrative or back-office jobs at UNC. More and more they’re forced to live in Durham or Wake County, areas that have more, and more affordable, housing options. Over time, that’ll lead to jobs relocating to areas where it’s easier to find employees. As Rod pointed out, there’s nothing that’s making UNC keep its administrative or back-office jobs in Chapel Hill, and he’d expect the university will move those jobs to Wake County in the next decade because the abundant housing options to our east will make it easier for the university to find and hire future employees.

The future will also be grim. Much of southeast Carrboro near downtown includes smaller single-family homes rented to students. With housing costs increasing, Rod suggests it’s likely many of those homes will be upgraded, converted, and sold to young professionals over the next 10 years, accelerating displacement of service workers as students relocate to Chapel Hill.

Locals may look at the apartments sprouting up in Blue Hill and think change is happening so quickly. But it’s occurring on the heels of a decade of very little growth in our housing stock. In fact, housing growth from 2010-2020 hasn’t been nearly enough to match demand.

A key need, according to Rod, is thoughtful planning. A major criticism is that the Town lacks good development standards which means every project is micromanaged. Outside Blue Hill, each application is subject to an expensive and complicated dance involving a developer, Town staff, multiple advisories boards, and council, all of whom are working towards ill-defined goals. Advisory boards ask for one thing and council requests the opposite, and the end result is individual council members debating the specific width of landscaping and number of trees along a particular street. It happened with East 54 a decade ago, and it happened with Aura earlier this year. Even where the Town does not micromanage, such as at Blue Hill, it doesn’t plan. Rod lays part of the blame for Blue Hill’s homogeneity over the town’s lack of neighborhood investment. There are few nearby amenities that might attract types of development other than big apartment buildings with their own swimming pools and community spaces. Instead of a few large projects, it’d be best to have more smaller projects, but Rod notes that developers need public amenities in order to sell those projects as part of a “place.” That “place” is wholly lacking.

Rod suggested two important next steps. First, the town should hire a top-notch planner who is skilled at urban design and at implementation; Brent Toderian from Vancouver was identified as a model. What’s needed is someone who can help create a good plan and get it implemented.

Second, hold community conversations about our future where there is explicit discussion not only of the options but also the trade-offs. Too often, he says, we focus on the benefits of a scenario and not what we lose with the choice. In my experience, that is something that happens frequently in Chapel Hill on individual development projects. Residents complain UNC’s Eastowne clinic looms too large over the highway, so we preserve more trees to protect the view of motorists at the cost of eliminating an off-road path for bicyclists and pedestrians. Existing neighborhoods don’t want traffic from new development, so we cut off roadway connections, forcing more people into their cars. A proposed housing development will take away some undeveloped land that the Town has never owned, so we buy the property for a never-planned park and delay indefinitely a broadly supported effort to build a cultural arts center. People don’t pay attention to long-term stormwater plans until it might impact their neighborhood, and so during implementation we delay addressing our stormwater issues and retrench and reanalyze. This happens continuously. Each of these disputes takes up Town staff’s time, leaving them unable to manage all their other existing duties AND do the type of long-range planning that leads to better outcomes.

The harsh conclusion: “The default choice of doing nothing will lead to a more Palo Alto-like combination of homogeneity and high housing prices.” Rod has worked on 10 projects in the Town over the last seven years, and he said this is the most consequential project that he’s worked on — and the one with the highest cost of inaction. That’s where our pitched fight over every development has gotten us. We’ve not only set Chapel Hill’s housing market on a bad trajectory, but given our location on the western fringe of the triangle we’ve put our future economic development at risk as well. This report is a clarion call for a change in direction. Otherwise, the future is grim.

Some other tidbits from Rod’s presentation:

- The town has done a poor job tracking new development over time, which means it’s like we’re flying a plane blindly in our efforts to comprehensively plan for our housing future. Data is missing or incomplete. His conclusion: We need much better information systems.

- 90% of jobs in Chapel Hill are filled by people who live outside the town; meanwhile, about 2/3 of Chapel Hill residents work somewhere other than the town, primarily in Durham and Cary/Research Triangle Park.

- Students comprise only 10 percent of new incremental housing demand in the town; the remainder is people of working age who want to live here.

- He expects that the Food Lion will close in the next few years, driving redevelopment of the shopping center, and that other retail developments may seek to redevelop as well. Planning will be key for those areas if we want new neighborhoods instead of more monolithic development.